The good news is that Oklahoma!, which is to the modern musical what Oedipus Rex is to Greek drama, is back. The not-so-good news is that London’s Royal National Theatre production, which was touted as the wonder of wonders, seems to have lost something in transit: Checking my feet, I found my socks still on.

“A much darker version” was the trumpeted hype, and though there may be a shade or two of darkening, this in itself is not a virtue. Definitely deserving, however, are Anthony Ward’s transporting sets and costumes (barring an unfortunate toy train), fervidly lit by David Hersey; the Robert Russell Bennett orchestrations artfully refurbished by William David Brohn and David Krane; sizable parts of Trevor Nunn’s direction and Susan Stroman’s choreography; and much of the performing.

That’s a lot, but there remains the problem inherent in all revivals of beloved classics: At what point does rethinking become thoughtlessness? The exact demarcation line is hard to find and harder to cleave to. Take the dances: Stroman’s are often strikingly inventive, tumultuously acrobatic, and provocatively spicy; but now and again, one misses the simpler, folksier, more heartfelt approach of Agnes de Mille. In the attempt to be more earthily realistic, for example, the title number has become a plausible post-wedding party but a far less rousing communal ode to the Oklahoma Territory.

Nunn’s direction starts with some breathtaking coups de théâtre, and further bright touches periodically pop up in alternation with less felicitous ones. The more complex interpretation of Jud Fry, bitingly sung and unsettlingly acted by Shuler Hensley, is to be hailed; the coarsening of Ali Hakim, redoubled by Aasif Mandvi’s lack of charm, is to be deplored.

Patrick Wilson is a winning Curly in singing, acting, bearing, and looks, and one wonders wherein may have lain Hugh Jackman’s widely affirmed superiority in London. Andrea Martin squeezes every last drop of bonhomie and deviltry out of Aunt Eller. Justin Bohon is the sweetest of Will Parkers, and dances entrancingly. Jessica Boevers is a pleasant enough Ado Annie, and the minor roles are flavorously taken.

The real problem is the chief import from London, Josefina Gabrielle as Laurey. Perhaps because she has been too long at it and grown too mature for the part, or because she is much more dancer than singer (unprecedentedly, she does her own dancing in the dream ballet), or because Nunn wanted her more tomboy than girly-girl, she emerges more contrived and unspontaneous, more starchily unfeminine. And, whoever is to blame, there is scant electricity between her and Curly.

Even so, the songs are there in the old, blessed profusion, the primary and secondary love triangles continue to triangulate, and the land continues to lure us city slickers. So take a leaf from Huck Finn in his urge “to light out for the Territory ahead of the rest,” and discover that as with the Post Office, Oklahoma! is OK with you.

Nothing pleases more than successful self-reinvention. Schmuel Gelbfisz’s trajectory from the Warsaw ghetto through profitable glove salesmanship in America as Samuel Goldfish to Hollywood mogulhood as Sam Goldwyn is a dream success story. For decades, Goldwyn’s movies and malaprops contributed to the nation’s – and world’s – merriment.

The authors of the play Mr. Goldwyn, Marsha Lebby and John Lollos, have caught the fascinating duality in a man who “thought Yiddish, dressed British,” and worshiped an art whose nature he only dimly comprehended. The play, which focuses on the making and marketing of Goldwyn’s comeback film, Hans Christian Andersen (1952), derives a skillfully seamless entertainment from crass fact and sentimental fiction, not entirely credible but steadily amusing.

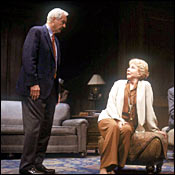

In Alan King they have a protagonist who knows both standup comedy and legitimate theater, and when to use which. His savvy blend of brazen shtick and quietly affecting passages – expertly directed by Gene Saks on David Gallo’s epically extravagant set – fills the stage with ebullient life. And King is cannily abetted by Lauren Klein as a sassy but adoring secretary, and by Joseph G. Aulisi’s suitably bespoke-looking suits.

Horton Foote, the gentle patriarch of the American theater, keeps turning out pieces about the fictional town of Harrison, Texas. They are rueful memory plays, bittersweet family chronicles, compassionate portraits of oddballs, losers, and rascals. You can smell the lavender sachets on them, if not indeed the mothballs, and they seem to be made up of faded photographs and yellowing newspaper clippings.

The Carpetbagger’s Children is one of these: the alternating reminiscences of three sisters about their family from Civil War times on down – a relatively happy family of the kind that, as Tolstoy noted, has no history. Brian Friel, miraculously, can make theater of these interlocking monologues of remembrance (from Foote, they are like the babbling of a nearby brook – fine for a summer picnic, uncomfortable when diverted to the stage).

This said, Michael Wilson and Jeff Cowie offer all direction and set design can, and Roberta Maxwell, Jean Stapleton, and Hallie Foote recollect away gracefully. But the tutelary divinity here is neither Thalia, the muse of comedy, nor Melpomene, the muse of tragedy, but Morpheus, the god of sleep.

No one can make onstage realism look more old-fashioned than Richard Nelson. This is not a fault if the characters are interesting, which in Franny’s Way they barely are. A grandmother (Kathleen Widdoes, not improved with age) takes two granddaughters, Franny, 17, and Dolly, 15, to New York City, to visit with her third grandchild, their cousin Sally. Sally and Phil, a young couple living in a Greenwich Village tenement, have just lost their baby daughter in crib death, and the atmosphere in which the weekend guests find themselves is fraught. Franny hopes to have more sex with her deflowerer, an NYU student. Dolly plans a secret meeting with her mother, who, having scandalously left the girls’ father for another man, has become taboo.

There is plenty of intrigue, but the intriguers do not manage to involve us. It might be different if the five performers were better actors or were (except for the Sally of Yvonne Woods) more appealing. Particularly off-putting are Elisabeth Moss and Domenica Cameron-Scorsese as the sisters. I am not sure that Nelson is his own best director, or that it is a good idea for jazz from a nearby club to obtrude throughout. What I am sure of is that a play with offstage sexual grunts and outcries in two separate scenes is pushing its luck.

Oklahoma!

Revival of the 1943 Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, directed by Trevor Nunn and choreographed by Susan Stroman.

Mr. Goldwyn

Starring Alan King.

The Carpetbagger’s Children

By Horton Foote.

Franny’s Way

Written and directed by Richard Nelson.

Photo by Michael Le Poer Trench.