What possessed the gifted Terrence McNally to write two such hokey plays as Full Frontal Nudity and Prelude & Liebestod, and speciously couple them as The Stendhal Syndrome? This syndrome, allegedly articulated by Stendhal, is explained in the show as the ability of great art to elicit intense emotional and physical reactions from sensitive viewers.

In Full Frontal Nudity, three American tourists are led before Michelangelo’s David by their female tour guide, oddly named Bimbi and so sensitive that after years of daily exposure David still takes her breath away. She leads a widowed, retired English teacher of uncertain sexuality, Mr. Charlotte [!]; Leo Sampson, a foul-mouthed macho punk; and Lana Maxwell, a dumb blonde who doesn’t even know there was such a biblical figure. David (projected from numerous angles and in great detail) turns all four of them into mutely gazing or lusting statues, which seems to be the point of the play, if there is one. The problem with it is that all four are so inconsistent as to be unbelievable. Would a mature guide have fainted at first sight of David? Would she, not even a native Italian, pepper her speech to ignorant Americans with fancy Italian phrases? And would her charges be no more than three? Would Mr. Charlotte, who knows the exact size of David, as well as Cellini’s Perseus, have trouble recalling the name of Goliath, but not that of Steve Reeves?

The play intermingles the characters’ thoughts with their utterances. Leo thinks, What did I fucking say? You gonna tell me I’m the only person looking at his dick? What else am I supposed to look at? Yet he will declare, “Show me someone who hasn’t suffered loss, and I’ll show you someone who hasn’t lived.” Lana thinks that David was the name of the sculptor’s model, yet will say, “If he is really a work of art, you can’t defile it. It’s greater than the sum of its parts.”

McNally’s characters aren’t people but counters for his prejudices, predilections, and cultural pretentiousness. This becomes even more evident in Prelude & Liebestod, primarily the interior monologue of a celebrated maestro while conducting that Wagnerian warhorse. His rather muddy stream of consciousness is periodically interrupted by the mute animadversions of his hostile concertmaster—often the one word, Asshole; the thoughts of the conductor’s wife in the left proscenium box, who loves him but yearns for her lover; the unvoiced effusions of a rabid young male fan in the right proscenium box, who fantasizes undressing the conductor with his teeth; and the reflections of the insecure soprano soloist such as, I’m supposed to kill myself because I’m not Kirsten Fucking Flagstad or Birgit Fucking Nilsson?

Not quite so simple are the bisexual conductor’s thoughts, which, besides quite convincing egomania, include gripes about his wife, lustful yearnings for the young fan, and excited recollection of a sadomasochistic orgy with a gorgeous Italian brother and sister. This playlet serves to show off McNally’s knowledge of classical music, as the previous one displayed his expertise in Renaissance art. It also exhibits a sophomoric love of four-letter words and a schoolboy obsession with sex, especially when kinky. Thus the conductor recalls himself tied up spread-eagled and gagged, and being manipulated by the Italian siblings: I can’t hold back any longer. I don’t want to and I come with an intensity that amazes me to this day and that I have never since, even remotely, equaled. I could feel my semen on my lips, on my cheeks, in my hair.

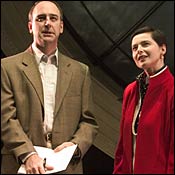

I can forgive McNally a number of things, only not that, in order to make the music match the time required for his play, he has the conductor lead and us hear the whole bloody Prelude & Liebestod a second time. Four actors, Michael Countryman, Jennifer Mudge, Yul Vazquez, and especially Richard Thomas (Conductor), do well. Isabella Rossellini, who has inherited neither her father’s talent nor her mother’s looks, does justice to her undemanding roles and delivers the guide’s Italian phrases meticulously.