If you’ve perused a fancy menu lately, you might pity the plight of the poor chicken. Every other protein, it seems, has been sanctified and name-branded, from Wagyu beef and Copper River salmon to the not-so-humble Berkshire pork. With the rare pedigree exception—a Giannone here, a Cloonshee there—the best a menu writer has been able to muster about chicken was that it was—yawn—free-range.

Thanks to the drive of a Canadian poultry breeder named Peter Thiessen and Bob Shipley, the well-connected manager of a California farm cooperative, chicken’s place in the epicurean pecking order is about to change. A new boutique bird has been clawing its way onto some of the ritziest menus recently, from Per Se to Alain Ducasse, where it’s roasted whole, wheeled into the dining room, and displayed like a trophy before it’s carved and anointed with jus. The Blue Foot, or Poulet Bleu as it’s sometimes called, is a homegrown version of France’s mythical poulet de Bresse—a bird so esteemed that in 1957 it was awarded A.O.C. status, which basically means that unless it grew up foraging the fertile fields, tucking into the occasional worm or snail, and lapping up the pure spring water of its designated region, then it ain’t Bresse—blue-footed or not.

This fact seemed of minor importance to Shipley, or Squab Bob as he’s known in poultry circles, who encouraged Thiessen to try to breed a Bresse-like chicken in the late eighties. In the meantime, D’Artagnan’s Ariane Daguin had been trying in vain to transport the Bresse bird to America—sometimes as eggs smuggled in a suitcase. Her entreaty to Georges Blanc, legendary chef and president of the Comité Interprofessionnel de la Volaille de Bresse, had been met with an imperious Non!, accompanied, one might imagine, by a haughty cluck. Finally, after years of trial and error, Thiessen engineered a bird that sent Vancouver’s French chefs into a tizzy and eventually made its way to one of Shipley’s co-op’s Central Valley farms, where it’s now bred exclusively and distributed on the East Coast by D’Artagnan.

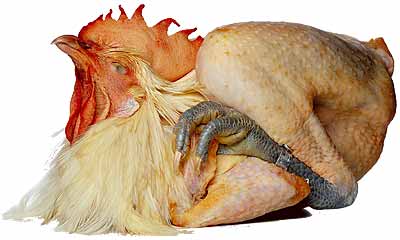

Like its French counterpart, the Blue Foot has a red comb, white feathers, and steel-blue feet—a characteristic so prized that they’re usually left on for tableside presentation. It’s slaughtered later than mass-market birds, and then air-chilled, two factors that contribute to a firmer texture and a slightly gamy flavor. It might be the closest we’ve come to le vrai Bresse—“just as good,” Ducasse’s French-born Tony Esnault diplomatically declares, although Craft’s Tom Colicchio demurs that nothing quite compares to a Bresse. Still, the proof is in the pudding, and after these birds have been variously lavished and coddled—butter-basted by Esnault, poached in consommé and served with tiny dumplings by Hearth’s Marco Canora, draped with prosciutto and festooned with Medjool dates by Colicchio—they can’t help but be delicious. The bottom line, as Canora puts it (and if all goes according to plan, the following might one day be construed as the highest praise): “They really taste like chicken.”