Medical Miracle #2

Problem: Fifteen-year-old girl. Born with a rare disorder that left her bent 90 degrees at the waist. Multiple surgeries and a steel rod in her spine failed to correct the problem. Her spine would have to be cut apart to be rebuilt.

Doctor: Oheneba Boachie-Adjei

Patient: Krystle Eginger

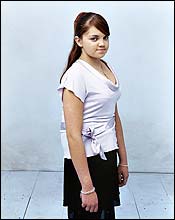

Looking now at Krystle Eginger, a red-haired 17-year-old with posture that would make a ballerina proud, you’d never suspect that she’d spent most of her life bent forward 90 degrees at the waist. Krystle was born with VATER syndrome, a mysterious genetic disorder. Its name is an acronym for the myriad abnormalities it creates: vertebral, anal, tracheal, esophageal, and renal. Krystle had serious problems in all of those areas, but the most visible was a complication called chronic kyphosis.

A cousin of scoliosis, kyphosis curves the spine back-to-front rather than sideways. It appeared as a small hunch when Krystle was 2; from there, says her mother, JoAnn, “it just progressed.” By the time Krystle was 8, she was bent nearly in half. She couldn’t lie on her back, even for X-rays. She’d get winded after taking a few steps. Gym class, sports, and ordinary play were all impossible. Her backbone nearly poked through her skin. “It was so painful we couldn’t touch her,” says JoAnn.

A surgeon near the family’s upstate home put a steel rod in Krystle’s back, but it too started bending. She spent six months in a body cast, then, at age 9, underwent a spinal fusion, in which several vertebrae were irreversibly joined. It’s a tricky procedure, especially in kids. Weld too many vertebrae together and you impede growth. Weld too few and the young spine can keep on bending, as Krystle’s did. Her doctor did another fusion: another failure. After that, says JoAnn, “he said there was nothing else he could do.”

For the next six years, Krystle lived a difficult life. Nicknamed “Hunchback,” she regularly came home from school crying. In January 2003, midway through her sophomore year, Krystle left high school. “Everybody made fun of me,” she says. “It was too hard.” The constant pressure from her bent back was damaging her internal organs, knocking out one kidney and reducing the other to 30 percent of its function. “At 20 percent,” says JoAnn, “we’d have to start looking for a donor.”

Then JoAnn was referred to Oheneba Boachie-Adjei, chief of scoliosis service at the Hospital for Special Surgery. Sitting in Boachie-Adjei’s exam room for the first time that spring, says JoAnn, “I didn’t think anything would change.” Then Boachie-Adjei walked in, holding Krystle’s X-ray. “He told us he could help us. I was shocked.”

Krystle’s case was “one of the worst I’ve ever seen,” says Boachie-Adjei. Because Krystle’s back had been fused, he couldn’t straighten it by manipulating vertebrae. Instead, he’d have to cut out the bent portion of the spine and reconnect the straight pieces above and below artificially. Such surgery, at a major gathering of blood vessels, risks fatal hemorrhaging. And he’d have to “leave the spinal cord hanging, with no structural support” for much of the operation. One wrong move and Krystle could be paralyzed or die. “We were scared,” says JoAnn, “but Dr. Boachie said, ‘If this was my daughter, I would do it.’ ”

On April 7, 2003, Boachie-Adjei opened Krystle’s back, cut the middle portion of her spine into pieces, and removed them. Once the bone was gone, he fitted a titanium-mesh cage around the exposed spinal cord, then attached the cage to the remainder of her spine with bone grafts. Boachie-Adjei added a steel rod on each side, then sewed Krystle up. When she woke up the next day, Krystle’s spine was straight. The day after that, she stood up. In a week, she went home. “I couldn’t look in the mirror until I got home,” she says. “I just couldn’t. But when I looked, I cried. Happy cries.”

After a month of physical therapy, Krystle ditched her walker and went shopping for clothes she’d never have worn before: a halter top, skirts. She started dating. By September she was back in school. “Everybody treated me like I was one of them, like nothing was ever wrong,” she says. “It wasn’t weird—it felt good.”

Krystle is four feet eleven and is unlikely to grow much taller. She can’t twist without moving her whole body, and she often gets sore in her thighs and abdomen as she relearns to use her muscles. But her kidney function is up to 50 percent, she’s getting good grades, and she’s volunteering at a physical-therapy center. This summer she wants to get her driver’s license. “I’m a little leery,” says JoAnn, “about that one.”