Valavanur A. Subramanian, Minimally Invasive Heart Surgeon

The Chairman of the surgery department at Lenox Hill Hospital, Valavanur Subramanian was the first physician in the country to conduct what’s known as midcab (minimally invasive direct coronary-artery bypass) heart surgery, in which arteries are bypassed through small incisions without opening the sternum.

You’re a pioneer of “off-pump” heart-bypass surgery, in which you operate on a beating heart without the aid of a heart-lung machine. How many of your patients qualify for this?

We do them all this way—one third of them with smaller, two-to-three-inch incisions and the rest with larger incisions because you have to bypass two or three arteries.

How many of them have to be switched to a heart-lung machine in mid-procedure?

Out of 2,000 patients, just 2.6 percent. And in the last two years, it’s just been 0.9 percent. The defenders of on-pump say the pump has worked well for 50 years. I always say the beating heart has been good for ages.

What’s better about it?

There is less length of stay at the hospital, and they’re extubated more quickly. Even staunch defenders of on-pump bypasses do off-pump operations on patients they view as high-risk—patients who had previous surgeries or angioplasties which made going on-pump and through the sternum a difficult decision to make. So we asked the question, if it’s good for higher-risk, why isn’t it good for lower-risk?

You’ve recently made the procedure even less invasive—with the help of a robot.

Yes, it’s called robotically assisted multi-vessel bypass. We use the robot to make a small incision where we can see everything. Then we operate with the help of an endoscopic stabilizer, a positioning device that can move the heart via a separate hole in the chest. The patient goes home in 48 hours. The sternum is never opened. In just the last couple of months, we did the very first triple bypass this way. It’s a real breakthrough.

Will everyone operate with robots in the future?

The younger generation of surgeons are more skillful at playing with technology. They’re into video games. And they’re adopting this robotic technique. It’s a mind-set. It’s going to happen.

How old are you?

I’m 63. But I’m young at heart.

-ROBERT KOLKER

Carolyn Brockington, Neurologist

Carolyn Brockington is your basic New York overachiever: Vassar grad, former Mount Sinai chief neurology resident, and director of Beth Israel’s Stroke Prevention Program—by age 33. Now, still shy of 40, she plans to devote the (many) years ahead to finding new ways to prevent and treat strokes, especially among African-Americans.

What got you interested in stroke prevention?

For a long time in neurology, doctors would go in to see a patient with Parkinson’s or MS or stroke, knowing they weren’t really going to be able to accomplish anything. But when I graduated from medical school, things were changing, especially with strokes. Hospitals were beginning to administer medicine intravenously to burst open a clot and restore blood flow. It’s exciting to be at the forefront of new things. I feel I’ve arrived at the right time in the right place.

What makes New York a good place to work with stroke patients?

We have the best technology and large, high-quality academic institutions, so we’re able to offer comprehensive care—I work together with neurosurgery, radiology, and rehab to treat my patients. The flip side is that it’s hard to get acute patients into the emergency room quickly. Coming from the West Side to the East Side—in rain, during rush hour—isn’t easy. The most effective treatment we have for combating the effects of stroke—intravenous t-PA—only works within a very short window: three hours after the first signs of symptoms. So if you don’t get the patient in on time, what good are the technologies?

Many people don’t seem to realize how critical it is to get help fast. Why is that?

For many years, people who suffered heart attacks didn’t think it was an emergency. Now people go straight to the ER. We want to do the same with stroke—to get people to realize it’s an urgent situation.

You do a lot of outreach, especially in the black community.

Being an African-American, it’s important for me to focus attention on groups with a high incidence of stroke, such as African-Americans and Hispanics. I lecture at the hospital and at community centers, and I do screenings at churches like Abyssinian Baptist in Harlem. We discuss ways to prevent stroke and to identify its symptoms. It’s not glamorous work, but hopefully we’re empowering people.

-TARA MANDY

Marcus H. Loo, Urologist

When East meets Upper East Side: Fifteen years ago, when Marcus H. Loo (who is the first to make jokes about being a urologist named … ) finished his residency and joined a Park Avenue practice, he simultaneously opened a Canal Street branch. He’s been shuttling back and forth ever since, building cultural and therapeutic bridges.

What is your own background?

My parents grew up in China and came to this country in the forties to go to university. I was actually born at Columbia Presbyterian. My father, being a businessman, moved us to Hong Kong when I was young. I always greatly admired my dad in that he could go seamlessly from speaking English to Chinese.

Is the patient-doctor relationship very different on Park Avenue and Canal Street?

Down here, to see a Western-trained doctor is a great leap of faith. Patients will often see a traditional herbalist or acupuncturist first, and if they aren’t improving, they’ll come to me. Whereas the patients on Park Avenue are often very well-informed.

How do you tap into an insular culture?

The Chinese community is actually quite small. The majority of the news that they get is through two newspapers. And it’s changed considerably. I have patients asking about in vitro fertilization, laparoscopic surgery. When I first started, a Chinese male would never voluntarily talk about erectile dysfunction. Now he’ll ask about Viagra.

What do you say to people who insist on going to herbalists?

I don’t dissuade them. But I always tell them that we’re here if you’d like another viewpoint. When people don’t have a grounding in Western medicine, how do you communicate that they have a cancer of the kidney that they can’t feel, that is causing the blood in their urine, and that if you don’t take it out, it’s going to progress? I often tell them to bring their family in. That helps.

How has your work affected your own cultural identity?

Ultimately it’s about the impact on my kids. I live in Westchester. And a lot of the Chinese-American kids, when their parents suggest going to Chinatown, they say, “I don’t like the food, it’s dirty.” My kids love it. I’m as American as anybody. But if you’ve been privileged to get a good education, you have to give something back. Park Avenue doesn’t need another urologist.

-BORIS KACHKA

Alejandra Gurtman, Infectious-Disease Specialist

In the age of SARS, AIDS, anthrax, and smallpox, the fight to wipe out the world’s deadliest bugs has never been more urgent. As clinical assistant for the Division of Infectious Disease at Mount Sinai Hospital, the founder of the hospital’s Travel Health Program, a consultant to the city on anthrax and smallpox, and principal investigator of the AIDS International Training and Research Program, Alejandra Gurtman is a one-woman germ-fighting army.

You started your career just as HIV was exploding. What was that like?

When I started, in 1983, I felt I had the tools to make a big impact on someone’s life—maybe even to cure them. But after HIV, the focus went from fixing the patient to managing long-term relationships. I’ve seen HIV moms deliver babies, and grandfathers see their grandchildren born. It’s been amazing.

Recently you’ve been focusing on travel medicine. Why?

It sort of happened by accident. People would call me and say, “I’m going to South Africa. What shots do I need?” Mount Sinai didn’t have a travel program, so I created one. We offer pre-trip advice, immunizations, and post-travel treatment. It’s been recognized as one of the best programs of its kind.

How has SARS changed travel medicine?

For one, it’s helped people realize the importance of seeing an expert before traveling. People often don’t consider that, especially if they go to “safe” destinations like France or Italy or Canada.

Are you worried about sars coming to New York?

Yes, but we’re fortunate because we’ve learned from other countries and we’re better prepared now than they were to contain it.

You’ve worked with the city on anthrax and smallpox.

A year before 9/11, I started talking to city agencies about working on an anthrax vaccine, and they said, “No! Too scary.” But a week after 9/11, I was asked to join an advisory committee on bioterrorism. We met with Mayor Giuliani twice a week at the command center; our job was to educate him. Then the anthrax cases started to appear, and I was asked to treat patients from the New York Post. On smallpox, I’m starting two new studies in the summer; we’re hoping to create a safer vaccine.

What breakthroughs in your field do you hope to see in your lifetime?

I think we may have vaccines for HIV, for diabetes, for MS, even for cancer. In the same way vaccinology was taken to a different level in the twentieth century—think of the eradication of smallpox—it’s going to be taken to a different level in the twenty-first. And I really wish for an HIV vaccine.

-TARA MANDY

Steven Schwarz, Pediatric Gastroenterologist

Treating children with severe developmental disabilities is no small task: Often the patient can’t speak at all, let alone articulate what, specifically, hurts. As chairman of pediatrics at Brooklyn’s Long Island College Hospital, Steven Schwarz has discovered that solving his patients’ nutritional problems can dramatically transform their overall health.

What kinds of nutritional problems do you treat?

Take a child with severe cerebral palsy. Even swallowing may be impossible. If you can’t swallow, you can’t eat. You’ll never build stronger muscles. It’s devastating. Half the time, you have institutions where workers have to spend every hour of every day just trying to feed these kids.

So what’s the solution?

We’d likely do a surgery called a percutaneous gastrostomy, where a feeding tube is inserted directly into the stomach. Amazingly, sometimes we can remove the tube a year later because the muscles have grown strong enough for the child to to eat!

And what about other situations?

We see a lot of kids with acid-reflux problems, which is common in a lot of the population but can be really troubling for children. Also, autistic children often have more idiosyncratic problems—like they’ll refuse to eat or drink completely, or won’t eat anything textured, or will eat but not drink and end up incredibly dehydrated. We use intensive therapy to broaden their culinary universe.

What do you find most rewarding about your work?

People sometimes say to me, “Why are you doing this?,” meaning that I deal with people with very little potential, people who are a drain to the health-care system. But what people forget is that the parents really love their children—helping these families, that’s the reward. Who am I to say who’s “worth it” or not?

-DAVID AMSDEN

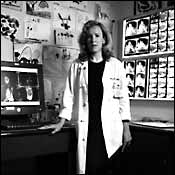

Hollis G. Potter, Orthopedic Radiologist

She may not feel your pain, but chances are she can find out what’s causing it. Hollis G. Potter, chief of magnetic-resonance imaging at the Hospital for Special Surgery, has developed innovative imaging techniques that often uncover conditions that get overlooked by general radiologists, such as cartilage tears in the hip. Her work has led to funding for a state-of-the-art research facility, to open at the hospital this summer.

What sets your technique apart?

Traditionally, X-rays just looked at bones. What MRI has been able to do, and what I have developed, is a way to look at soft tissue, particularly the cartilage, which is absolutely essential for the diagnosis of any orthopedic condition. As a result, we can detect even the most minute tear or fracture as well as get information about the pattern of injury. And for the first time, we can actually look inside a total hip replacement to see if there is any particle-wear disease, from plastic or metal, that eats away at the bone. Putting a big piece of metal into a magnet used to be considered heresy. A lot of places still won’t do it.

How does it work?

Instead of using the standardized large coils, we place smaller ones on the patient to zoom in on elusive soft tissues and bone fragments. Equally important are what are called pulse sequences. I can manipulate those to get different types of diagnostic information.

And the result?

Typically MRIs use a large field of view—for example, as much as a third of the arm to study a wrist. What we are able to do is to focus on the smallest ligaments. We just see the wrist, not fingertips or forearms or elbows. We can even look at a knuckle. We’ve come up with a whole new way to use MRI for orthopedics—figuring out which diagnoses we’re consistently missing.

Ever had an MRI?

Before I had research assistants, I was my own guinea pig. As a patient, I would want a radiologist with a measure of expertise in her specialty, not one who jumps from one area of the body to the next. Too many people just go to the most convenient place when they should select a radiologist with the same care they would put into choosing a cardiologist or neurologist.

What do you love most about your work?

Every case is essentially solving a puzzle, and 90 percent of the time, we do. For example, no one has an unexplained joint swelling. It has to be inflammatory or traumatic or infectious. And the answer is always there on the film. You just have to know what to look for—and also have that extra spatial resolution and light source. Essentially, I have put new batteries in a dim flashlight.

-PATRICIA BURNSTEIN

Richard Barakat, Gynecological Surgeon

The chairman of Memorial Sloan-Kettering’s gynecology department, Richard Barakat specializes in cancer surgeries—from fertility-preserving cervical-cancer procedures to extensive ovarian-cancer removals, like the one taking place during the interview below.

You’re only 43—isn’t that a little young to be head of your surgical division?

What were they thinking? Maybe Doogie Howser. But I’ve been at Memorial Sloan-Kettering for fourteen years, and I’ve been in this division longer than anyone else. Nurse—sweetheart retractor! [Aside] I’m not being fresh with the nurse—this tool really is called the sweetheart retractor.

Tell me about today’s case.

I’m taking out the colon, uterus, and the ovarian-cancer tumor as one mass. Then I’m putting the colon back in and hooking it back up to the rectum. It’ll be a little shorter, but she won’t notice.

What are all those big yellow bumps?

Tumor! You gotta hate it! Look—there’s even a nodule on her appendix. She’ll probably need her spleen out—I can feel a tumor there. But functionally she’s gonna be great. She’ll urinate, she’ll eat. Her bowels and bladder will work. She’ll be like someone who had a hysterectomy.

This isn’t particularly delicate work. You’re really manhandling the organs here.

Yes. And you know, it has to be that way. It’s physically taxing. You have to tug and pull to get this stuff out. It’s a disease that you have to hate. You have to go in with that mind-set.

Are all ovarian-cancer operations this severe?

Most women have advanced cancer by the time they get here, because ovarian cancer is so rarely diagnosed early. But the good news is it’s chemo-sensitive. The more you remove, the better off you are. We call it being “de-bulked.” So we optimally de-bulk everyone here. We do very aggressive work. We cure maybe 35 percent of the women with advanced-stage cancer, but that’s getting better, with so many new drugs to prolong the life span, with long periods of remission.

This surgery will take six hours. Don’t you get exhausted?

I don’t feel it in the OR, but I feel it the next day. So I only do it every other day. Surgery is skilled construction work; it’s a lot of labor. But there’s nothing more satisfying than looking in and seeing such a mess, and when you finish, the patient is clean. You keep saying to yourself, Will she survive? She’s got chemotherapy to go through yet. But at least I’m giving her a fighting chance.

-ROBERT KOLKER

Mordecai Zucker, Family Practitioner

Mordecai Zucker’s patients in the Five Towns and the Rockaways call him “the Angel.” Little wonder. In 50 years of practicing family medicine, he has logged over 45,000 house calls, and he still does three or four a day, year-round. “Illness never takes a holiday,” says Doc, his preferred title.

Why house calls?

I see a lot of patients caught in the limbo of not being sick enough for hospitalization yet not being well enough to get to the office. I want people to know that medical care is still available.

These are mostly elderly patients?

The majority of my patients are over 80. At that age, going to an emergency room is not a real alternative. Because the emergency room works on a triage level, actual emergencies like arterial bleeding or cardiac arrest come first and patients like mine are taken care of last.

Isn’t it true that many tests can only be done in the hospital?

Actually, sophisticated technology—for example, portable X-ray machines and chronic respiratory devices—can now be provided in the home. I myself take a cardiogram on house visits, and either I draw blood or get the lab techs to go.

What does a house call cost these days?

The majority of my patients have Medicare, which allows about $50 for a simple and $80 for a more complicated visit—cheaper for the government, by the way, than an emergency-room visit reimbursed at $125 minimum.

Most unusual house call?

I delivered our neighbor’s baby, something I hadn’t done since getting out of medical school in 1951. It was back in the early seventies, during a monstrous snowstorm that totally shut down the roads. I took a sled to pull her to the hospital, but after a few blocks, with at least a foot and a half of snow, that became impossible. I stopped in front of the home of our rabbi, rang the bell, and asked, “How would you like to have a delivery in your house?” It felt like frontier medicine. We put her in bed and got the sheets ready. “Don’t be afraid,” I told her. “Look around the room and you’ll see I’m the only doctor here, so you have the best doctor in the house.” She delivered a fine baby girl. Then the rabbi, her husband, a neighbor, and I fashioned a stretcher from a day cot and carried her out to the front seat of the only vehicle moving, a sanitation truck, which drove her to the hospital. When her daughter got married twenty years later, I was one of the witnesses.

-PATRICIA BURSTEIN

Harold S. Koplewicz, Child Psychiatrist

Harold S. Koplewicz loves working with children, even if he walks away with some bruises. As vice-chairman of the Department of Psychiatry and professor of clinical psychiatry and pediatrics at NYU, he founded and directs the Child Study Center, which focuses on brain research.

What interested you about this field at first?

When I started my internship in the late seventies, the thing that interested me most was behavioral or emotional problems. Pediatric neurology, though intellectually stimulating, was depressing. There was so little you could do. But psychiatry was about to have a revolution. It was moving toward an understanding that nature had more to do with the problems than nurture. I had previously thought that I could take care of people by being nice to them, like Judd Hirsch in Ordinary People—to save them from cold mothers like Mary Tyler Moore.

What sparked the revolution?

Discoveries in psychopharmacology and the neuroscience of child mental disorders. We can now change and save lives. We can give a child back his childhood.

How pervasive is the problem now?

In 1999, the surgeon general said that 12 percent of the population under 18 had diagnosable psychiatric disorders, and that’s not including addiction. That’s 10 million children, and over each of the last 40 years, about 2,000 teenagers committed suicide. This shouldn’t only matter to parents who have a sick child; you should be concerned about the child sitting next to yours. Look at Columbine.

Is there resistance to treatment?

There are myths that get in the way. One is that it’s the parents’ fault. So they like to hope it’s just a bad phase. Then there’s the myth that we are overmedicating, that kids like to take drugs. But the truth is that most teenagers just want to be like everybody else. No one is having a Prozac party.

Any exciting new breakthroughs?

Our better understanding of the role of the brain in dyslexia and ADD and our knowledge that the brain changes during different stages of development is incredibly important. Turns out that ADD kids have 3 to 4 percent smaller brain volume than normal kids. We also now know that there is a dramatic change in the brain during adolescence, for instance, and that puts teens at a higher risk for depression.

What gives you the most satisfaction?

There is nothing more gratifying than having a kid who tried to bite you come back years later to ask you for advice.

-BETH LANDMAN KEIL

Dr. Carol Levy, Endocrinologist

Physician, heal thyself: Two years ago, this 39-year-old Long Island native left a lucrative Upper East Side practice for New York-Presbyterian Hospital/ Weill Cornell Medical Center, to focus on diabetes, a medical passion that’s equal parts professional and personal.

You had juvenile diabetes, right?

If you get diabetes, you still have it. I was diagnosed when I was 7. It’s a misconception that certain types of diabetes, like juvenile diabetes, are more severe than others. Diabetes is diabetes. You have the same goal, the same risks.

Why did you decide to specialize in diabetes? I was a second-year resident on diabetes rounds, and a patient came running up with a bunch of questions. I was able to answer every single one comfortably—and this was my second year, when you usually don’t feel that comfortable. The patient said things like, “It hurts when I test my blood sugar.” And I said, “Maybe if you use the side of your finger, it won’t hurt so much.” And I thought, Wow, this is a way that I can help people in a different fashion.

How else does your own experience help?

Every so often, I’ll have a very difficult patient who’ll say, “What do you know?! You don’t have diabetes.” And I’ll say, “Well, actually, I’ve had it for 32 years.” Frequently, I’m just using my experience to motivate someone else. Diabetes is more of a self-management disease than anything else. And managing it is about motivation, not just intelligence. I have a lot of patients who aren’t the brightest people in the world who take wonderful care of themselves, and then I have some CEOs who don’t.

Your subspecialty is gestational diabetes, which is only diagnosed during pregnancy. Is that a big issue?

Yes, particularly in New York, where women wait until they’re older to get pregnant.

And you just had your own first child.

That was a very eye-opening experience. I’ve taken care of hundreds of pregnant patients with diabetes. But having been pregnant and realizing how hard it is to manage diabetes, your career, and your home life—I think it makes me a better doctor. You feel like you’re a role model.

-BORIS KACHKA

Who Decides?

There are some 50,000 doctors practicing in the New York area. Choosing the top 1,300 isn’t something we take lightly. So for the sixth consecutive year, New York Magazine has drawn on the expertise of Castle Connolly Medical, the research-and-publishing company, to assemble the “Best Doctors in New York” issue. The 2003 list is essentially an excerpt from the eighth edition of Castle Connolly’s Top Doctors: New York Metro Area, which will be published this month. (Available in bookstores, or by calling the publisher at 800-399-DOCS or visiting castleconnolly.com.) The selection process began last year, when questionnaires were sent to 16,000 top physicians in the New York area. Nominees were sought in almost every specialty, with the emphasis on direct patient care. The list was further refined by hundreds of interviews with leading specialists, chiefs of service, and other hospital personnel, conducted by Castle Connolly’s physician-led staff. One notable change in this year’s list: We have not included any cosmetic doctors. Those physicians will be featured in an upcoming issue devoted entirely to cosmetic medicine. Look for it later this summer.