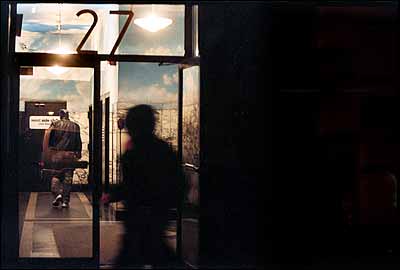

Chelsea’s West Side Club (Photo Credit: Edward Keating)

Maybe the 46-year-old New York man who had managed to avoid HIV for the life of the epidemic finally succumbed on Friday, October 22, 2004, when he failed to use even one condom during a weekend of crystal meth and multiple sexual encounters. Ordinarily, the New York man was sexually dominant, the penetrator. That changed on October 22. “Apparently he used Viagra, but when he didn’t, he became a bottom,” says Dennis deLeon, a grandee in AIDS politics who has been briefed on the case. “Crystal can make anybody a bottom. I’ve heard stories that even straight guys flip over on this stuff.”

Maybe he was at the West Side Club that night, as one report says, and maybe out of the steamy recesses of the place came a man, as yet unidentified, who probably knew he was HIV-positive, who knew that his infection was defying treatment. Through the distorting lens of crystal, the New York man reportedly had hundreds of encounters around this time—and seven or eight that evening alone.

Let’s say most of these strangers assumed the man was himself HIV-positive, which would account for why none of them insisted on a condom either. Many gay men practice this gambit, colloquially called “sero-sorting,” based on the belief that having unprotected sex with somebody who shares your HIV status carries minimal risk. Most doctors believe otherwise, and point to the danger of reinfection. Studies show that in such encounters, those who are positive tend to assume their prospective partners are positive, and negatives make the opposite—and equally unspoken—assumption.

And maybe on that long night in Chelsea, the worst possible thing happened: This New York man contracted an extremely deadly “superbug” like nothing ever seen before. It appeared to carry a dreadful punch. While most people go a decade after infection before showing major symptoms, this man sank to a sickly shadow of himself by mid-November, and was an AIDS patient by December and a curiosity by January, when tests showed him resistant to most AIDS drugs. By February 11, when the New York City health commissioner, Dr. Thomas Frieden, called a press conference to alert the world to the case, the man had become a modern-day Typhoid Mary, Patient Zero in a foreboding new epidemic threatening New York City and the globe.

“We’ve identified this strain of HIV that is difficult or impossible to treat,” Dr. Frieden announced ominously. “Potentially, no one is immune.”

With those words, this man’s misfortune became the biggest AIDS story of the 21st century, shouted in headlines as far away as India. The New York Times discussed the supervirus in twelve stories in the first week alone. The alarm about the drug-fueled, sexually irresponsible gay-male community has given new fodder to old anti-gay mouthpieces. “There’s a new strain of HIV available in New York City. It’s because of gay men,” the Catholic League’s William Donohue said on MSNBC. “They’re endangering the lives of everybody.” Even William F. Buckley, who twenty years ago suggested the rumps of HIV carriers be branded with warnings, reentered the fray. “Murderers need to be stopped,” he explained in National Review.

Panicking about the new pathogen, most gay men didn’t race to denounce Buckley this time. Instead, they raced to their doctors. Physicians across the country reported a crush of visits from worried patients; the Gay Men’s Health Crisis Website experienced a 63 percent surge in hits. At two heated community meetings in Manhattan, gay men and AIDS service providers swapped accusations with rancorous outbursts reminiscent of early ACT UP meetings. Only this time, the anger was directed less at the health Establishment than at the patient himself. “My first reaction was one of anger—that someone in his mid-forties, who had escaped the devastation and pain of the eighties and nineties, had seroconverted,” Tokes Osubu, executive director of a Harlem-based group called Gay Men of African Descent, told more than 300 people gathered at FIT in early March. “We have lost that sense of outrage. Many of our friends and lovers are dead, but we are not afraid anymore.”

After the frenzy died down, however, the new epidemic began to look a lot less fearsome. In fact, on closer examination, almost everything about this case seems murky. An investigation by the Department of Health turned up no evidence that the New York man passed the virus to anybody. And on March 29, the department put out a press release saying that the patient was responding well to his medications.

“The virus that ate New York,” as Richard Jefferys, basic-science project director for Treatment Action Group, put it, “is just one case.”

The responsibility for this medical panic attack is spread widely: from the patient to the reporters who made him a caricature, to the city health commissioner for terrifying the city and the scientists who characterized the case, most notably Dr. David Ho, the top researcher at the world-renowned Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center at Rockefeller University, and his deputy, Dr. Marty Markowitz, who warned of a “silent tsunami” of new infections spreading undetected across the land.

“There were all these signs that said, ‘Slow down, take this with caution’—and they just weren’t heeded,” says Martin Delaney, the founding director of Project Inform, an AIDS-information clearinghouse. “Everyone down the line miscalculated. It was like a perfect storm; every element had to be in place for this to happen the way it did.”

The bar scene at View on Eighth Avenue. (Photo Credit: Edward Keating)

Let’s go back to October 22, a warm and clear night in Chelsea. According to Dr. Larry Hitzeman, a colleague of the New York patient’s doctor at Cabrini Medical Center, the man had by then negotiated a long courtship with crystal meth. “For five years, he took it one time a month on average,” Hitzeman said at the FIT meeting on the case. “He was taking it every weekend for the past two years.”

The drug has become endemic among gay and bisexual men in urban meccas. Some users, like a 42-year-old man I have known for more than twenty years, can snort a few bumps every few months without escalation. “In my world, it’s an ordinary fixture,” he told me recently. “If you go out to big dance parties, late at night, you’re probably using a little crystal.”

But Crystal, for most, is one of the most dangerously addictive substances around. It is also a powerful disinhibitor, with a remarkable ability to concentrate the attention on sex for hours at a time. Invitations to “party and play,” or PNP, are often included in personal ads on sites like Manhunt and Craigslist. A recent survey showed that men taking crystal meth are twice as likely not to use condoms, and this man was no exception.

Among gay men, stories echoing the New York patient’s headlong collapse into addiction are commonplace. “It’s the most serious problem I’m dealing with,” says Dr. Paul Bellman, an AIDS specialist in Manhattan. And with crystal-meth use comes a predictable upsurge in risky behavior—increasingly, people who have avoided HIV for decades are suddenly contracting the virus in middle age. “The way I look at it, Chelsea is like Iraq,” says Bellman. “Every day, somebody gets blown up.”

On October 22, the patient was still sinking into the drug’s grip. He remembers staying up all night and through the next day, thanks to crystal. “He believes this was the night,” Dr. Markowitz told a group of AIDS doctors in February. His last HIV test was on May 9, 2003—like four previous tests, it was negative and his immune system tested normal.

His doctors have tended to credit his own theory of when he contracted the virus, in part because two weeks later he suffered severe flulike symptoms, suggestive of what is called acute seroconversion illness. About half the people experience these symptoms following initial exposure to HIV. By mid-December, he was rapidly losing weight, and his fatigue kept him in bed. Concerned, on December 16, he saw his doctor. The news came back almost two weeks later, and it was bad: a massive viral load of 280,000 copies per milliliter, and a near total T-cell obliteration. A normal T-cell count is 700 to 1,200; he had just 80. It meant that just two months after his presumed exposure, he had developed full-blown AIDS.

“This was alarming to me,” says Dr. Michael Mullen, the patient’s longtime physician, speaking about his patient for the first time. “You wouldn’t expect to see that sort of profile in early infection.”

On December 29, just before Mullen gave him the terrible news, the patient, assuming he was still negative, picked up a young man in a bar and, according to Markowitz, had insertive anal sex with him, potentially infecting him as well.

Mullen referred his patient to doctors at Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, among the most highly regarded facilities in the field. Under the direction of Dr. David Ho, the center has scored some of the most spectacular advances of any AIDS research team. Ho discovered the triple-drug-cocktail approach to treating HIV, credited for turning AIDS from a fatal illness into a chronic disorder, saving tens of thousands of lives. In 1995, nearly 50,000 Americans died of the disease; in 2003, approximately 18,000 succumbed, a fraction of the approximately 850,000 living with HIV. For his efforts, Ho was named Man of the Year by Time in 1996, famously edging out the likes of Bill Clinton and Mother Teresa.

Since then, he has authored a number of important papers on viral replication that have helped shape the field. While there’s broad consensus that different viral strains can produce different effects, Ho’s focus on the virus as the most important factor in the progression of the disease strikes many as overly narrow. Some doctors say this approach deemphasizes the immunological issues involved, or whether environmental factors, like drug abuse, might be contributing. This has not always been a gentle dispute. A number of years ago, Ho courted fury in the tightly knit field by ordering up lapel pins for his staff that declared, IT’S THE VIRUS, STUPID!

Despite the tensions, Ho is still broadly respected as among the world’s best AIDS minds. But more recently, the Aaron Diamond Center has had trouble living up to its reputation. It has quietly changed focus from basic research to vaccine investigation, a field that has not produced promising news in two decades.

To some degree, Ho and his center are victims of their own success. At least among affluent Americans, AIDS is seen as a manageable condition rather than a death sentence. Perhaps as a consequence, funding sources have been going dry. In IRS filings, Aaron Diamond reported $9.4 million in donations and research grants in 2003, the last available year, down dramatically from $20 million in 2000. Ho’s compensation package, meanwhile, has gone in the other direction—in the last reported year it was $518,000. With the stipends and consultancy fees from pharmaceutical firms, he is one of the highest-compensated medical researchers in the world.

An unusually large number of researchers have left over the years, many privately citing conflicts with Ho, whom they describe as a poisonous personality with little patience for dissent. In fact, many leading AIDS scientists, while giving him credit for leadership in the field, also criticize him for overplaying his king-of-the-hill standing.

The Blue triple-X video and buddy-booth parlor. (Photo Credit: Edward Keating)

Some wonder if he didn’t see potential in the mysteries of this new case. “David Ho has a huge shop that he has to maintain,” says Dr. Cecil Fox, an AIDS pathologist and veteran of many skirmishes, who owns a biotech company in Arkansas. “If he finds a new phenomenon, naturally he’s going to jump on it with all four feet.”

Ho denies he was under any particular pressure when the patient arrived at the center. “Think about this: We’re doctors, scientists, doing research,” he says. “Our mission is research.”

On January 17, the patient was seen by Marty Markowitz, Ho’s longtime research collaborator. Markowitz ordered more tests, which confirmed the dire clinical picture. The patient continued his precipitous decline, losing nine pounds in the next three weeks. His viral load rose to 650,000. Viral samples were sent to a San Francisco lab for resistance sequencing, tests that help determine which drugs are most likely to be effective.

Although Markowitz did not respond to interview requests, he has spoken often about the case in public. “Let me tell you, this guy told me he had four partners and no drug use,” Markowitz said at a meeting of AIDS doctors at the Strata restaurant in New York on February 15. “And I am a very difficult guy to fool. But he’s very charming, very handsome, very successful. You’d invite him to Christmas. You’d want your mother to meet him. He is not a demon. He’s a great guy. But he has … he has a dark side.”

Ultimately, he confided in Markowitz about how meth propelled him through the sexual underground. “This man,” Markowitz told the meeting of doctors, “has had thousands of sexual contacts over the past three years. I said it right. Thousands.”

In the weeks between his presumed exposure in late October and his diagnosis after Christmas, Markowitz learned, the man had swapped fluids with about ten other partners, unknowingly exposing them to his virus. This is one of the biggest problems with sero-sorting. People who don’t know they’re infected are responsible for more than 50 percent of all new infections.

This is why, despite all the internecine conflict, there’s unanimity among doctors on the issue of safe sex. Still, some people have proposed population-based sero-sorting as a way to slow the epidemic. And one study has led researchers to speculate that if men born before 1980 never had sex with men born afterward, the epidemic would eventually die out in the gay community.

“The way I look at it,” says AIDS specialist Paul Bellman about the influence of crystal meth, “Chelsea is like Iraq; every day, somebody gets blown up.”

While the rate of HIV transmission seems to have dropped in each of the past three years, case reports of syphilis and drug-resistant gonorrhea are soaring among gay men, suggesting more people are having unprotected sex.

Though he felt ill, the New York patient assumed he was still negative and no risk to anybody else, his longtime physician says. Still, he’s been vilified. “This guy is a total and utter asshole,” Larry Kramer told the New York Observer. “What happens is, this is what people think gay people are like. Now we can’t move forward, we can’t get to our place in the sun, because of stupid assholes like this.”

Michael Mullen emphatically defended his patient, who he says never engaged in unsafe sex after his diagnosis. “He’s so beat up about this, he would never, ever do something like that. That’s a total lie, a fabrication—it’s just not true.”

On January 22, a Saturday, e-mail arrived on Markowitz’s computer from the lab with resistance-test results showing the man’s virus was extremely mutated, rendering it less likely to respond to 19 of the 21 approved AIDS drugs. Markowitz had never seen a more resistant strain. The only thing that causes HIV to acquire resistance is sporadic exposure to anti-AIDS drugs—the virus, a clever foe, can seize the opportunity of poor drug adherence to change attributes and evade medication.

But that alone didn’t cause Markowitz great concern. What worried him was the fact that this mutated virus seemed to cause disease so rapidly. On average, HIV needs about ten years to bring on full-blown AIDS, though in a small percentage of infected people—perhaps 45 in 10,000—it progresses in under a year. Ordinarily, rapid progression is more likely associated with viruses that have few or no mutations; the more changes a viral strain undergoes to evade medications, the less potent it becomes. But here was a mutated and fast-progressing virus, a frightening combination. In addition, when Markowitz cultured the virus, he found it was at least as contagious as non-mutated viruses. Markowitz has said he ordered the standard tests, which look for the nine markers that make some people genetically disposed to progress quickly to AIDS—all that came back were negative. Markowitz came to the frightening conclusion that he was looking at a deadly new viral subspecies. “If you can’t see the horse and you want to see a zebra, that’s your prerogative. But the data here is incontrovertible,” Markowitz said.

Most leading researchers, however, were not so quickly convinced. Many viewed Markowitz’s analysis as overly influenced by the Aaron Diamond Center’s preconceptions. “It is fairly agreed upon that what produces rapid outcome is the host, not necessarily the virus,” says Dr. Michael Ascher, an immunologist now working for the federal government. “We just don’t know what all the factors might be yet.”

Markowitz and Ho had some indication of resistance and doubt among their colleagues when they submitted their findings to the Retrovirus Conference in Boston. When it was decided, after a peer-review process, that the results were not significant enough to be discussed on a panel, but instead should be displayed on a large poster board in a room with other research posters, Markowitz reportedly became furious. “He began to argue with the organizers, saying the poster would present a danger to the public health—because so many people were going to crowd around it, someone would be injured,” one attendee said. “People were scratching their heads.”

Markowitz also began work on an emotional op-ed piece he hoped the Times would publish—and when the paper chose not to, he began to circulate it himself: “As I write, the extent of this potential, silent tsunami is being defined,” he warned. “This untreatable virus with an aggressive clinical course can bring us back to the eighties and early nineties—the truly darkest years.”

“It was of course a stressful, emotional moment for him,” David Ho told me. “Marty saw that the man had a virus that was resistant to nearly all the drugs and he had a very aggressive course of disease, and that was sufficiently alarming to us to say, ‘Wait a minute: Because of his active sexual history, are there more such cases out there?’” This was difficult to ascertain, because many of the patient’s sexual contacts had been anonymous. Even those whose names he knew hesitated to come forward.

Lacking more evidence, many AIDS experts have questioned why news of this middle-aged man’s declining health went any further than this. “This is an unusual virus in its resistance patterns. That’s important,” says Dr. Howard Grossman, executive director of the American Academy of HIV Medicine. “But there’s nothing that suggests this is the beginning of an epidemic.”

On the same Saturday Markowitz got the alarming lab results, he e-mailed the New York City Department of Health. The alert reached Dr. Susan Blank, the assistant commissioner for the Sexually Transmitted Diseases Control Program, on Monday, January 24. According to Markowitz’s remarks in February, his dealings with them were heated. “The patient is sick in four months! He never got better really. Intractable pharyngitis, twenty-pound weight loss, bed-bound fatigue. These are bringing me back to the days of the eighties, and it frightened me so much that I stood on my soapbox and screamed and screamed and screamed until they listened.”

The news reached Frieden within a week. Appointed by Mayor Bloomberg in 2002, Frieden is an activist commissioner widely respected for his medical instincts and his political courage—his steady hand guided the administration through its biggest medical crusade to date, the successful and politically risky campaign to ban smoking in public places. But before entering politics, Frieden was an infectious-disease doctor, specializing in drug-resistant tuberculosis. For much of the past eighteen months, AIDS has been his top priority, and he has earned high marks so far. As early as this month, he expects to announce a controversial new approach to the epidemic in the city, which is still the AIDS epicenter of America. Citywide, more than 110,000 are infected—and 20,000 of them don’t know it. According to a draft of the report, which was leaked to me, he wants to change the state laws in order to streamline the consent process, making an AIDS test like other blood tests, while making AIDS testing much more widely available. “Knowledge is power,” he told me in an interview in his Chambers Street office several weeks ago. “Most people who know their status … do the right thing. So increasing the proportion of people who know their status is probably the single most important thing we can do to reduce the spread of HIV.”

Some activists are disturbed about this change. “It seems to me that’s a slippery slope,” says Tracy Welsh, the executive director of the HIV Law Project in New York. “Pretty soon we’re looking at universal testing—i.e., mandatory testing … And then what? Restrict their civil liberties? Criminalize their behavior?”

Frieden has been known to push the civil-liberties envelope in order to contain health risks. In New York in 1993, he helped establish detention centers for people with TB who refused to follow doctors’ orders. But while the commissioner has expressed grave concerns about patients who are courting HIV mutation by not following their drug regimens, he’s said he has no plans to make testing compulsory. Instead he wants to track patients’ viral profiles case by case and help their doctors find a better regimen if their virus is mutating. For the most part, AIDS leaders take him at his word. In fact, he enjoys support from traditionally antagonistic groups like the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS, GMHC, and the Harm Reduction Coalition.

At first, Frieden was skeptical of the supervirus case. “I asked both David and Marty, ‘How do we know this isn’t severe acute retroviral syndrome?’ And I asked people from around the country, too. ‘Could this be just a severe conversion reaction?’ And they said, ‘No.’ ” He also challenged the conclusion that the patient was newly infected. What if the patient’s flu symptoms were caused by something else—something as simple as the flu?

For the next week or so, Frieden conferred with other experts, including AIDS specialists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Then, on January 31, Department of Health investigators interviewed the patient, hoping to develop a list of those he may have exposed. However, because a majority of the original patient’s contacts were anonymous, Frieden says, “we started with less than a 50-50 chance.” Those men whose names he recalled were invited to talk; many reportedly declined.

He also contacted three dozen blood laboratories in the U.S., Canada, and Europe and asked them to canvass their records for evidence of viruses that matched this patient’s nucleotide sequences—potentially hundreds of thousands of samples.

Frieden then weighed various additional options, and sent out a blast-fax to a network of doctors. But he worried that some of these men weren’t symptomatic yet or had mistaken their symptoms for something more benign. “You want to generate demand,” he says. “You want people to think, Oh, I just had unsafe sex a couple of weeks ago, and I’ve got now what feels like a really bad viral syndrome. Maybe I should remind my doctor that they should test for HIV now. It’s important to do that, because the viral load and infectiousness of someone who’s recently infected with HIV is astronomically high.”

Ultimately, the decision to hold a press conference was Frieden’s alone. He assembled some prominent community leaders to join him on February 11. The next day, the story dominated the covers of papers around the globe.

The announcement detonated a long-smoldering debate in the gay community over sexual responsibility. “We are murderers, we are murdering each other,” says Larry Kramer, whose new book, The Tragedy of Today’s Gays, was published this month. “If intelligent, smart people are unwilling to take responsibility 100 percent for their own dicks, I don’t know how you stop the killing.” Some, like the columnist Dan Savage, saw in the case a reason to bring on a new penalty phase for prevention activism. “There’s a great deal of anger and frustration among gays and lesbians at the never-ending, nonstop coddling and compassion campaign that passes for HIV prevention,” he says. “There will be no sympathy when this happens to us again. We are not going to be the baby harp seals the way we were in the eighties and nineties. We picked up the same gun and said, ‘I hope it’s not loaded this time,’ and pulled the trigger again. And I’m gay—imagine how straight people feel.”

But others took a more skeptical approach. “I thought this sounded familiar, so I Googled ‘superbug’ and ‘AIDS,’” said GMHC’s Gregg Gonsalves. He found two cases reported in 2001 by a noted Vancouver AIDS specialist, Dr. Julio Montaner. The Vancouver Sun quoted Montaner about the cases, but he could have been describing the newest Patient Zero: “In a matter of months, these people have gone from totally asymptomatic to very low immune systems.”

Frieden says he was caught unawares by the Vancouver cases, and that he wishes he had known about them before deciding to hold his own press conference. Ho, who still maintains the uniqueness of the New York case, wasn’t aware of the specifics of the Vancouver cases, and called Montaner the Monday following the press conference. “It was very cordial,” Montaner says with a laugh. “He phoned me up to find out more about it.” (Both Canadian patients, it turned out, have responded well to treatment and now have fully suppressed viral loads.)

Ho, meanwhile, was coming under heavy criticism. “When I first heard this, I said, Holy shit—there is no evidence,” says Dr. Robert Gallo, an eminent virologist. “Clearly, conclusively, scientifically, it was inappropriate to make that statement.”

Gallo and other leading figures in the field—including Dr. Tony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—believe the new case report, while unfortunate for the patient, is likely a statistically predictable outlier. Unfortunately, according to data generated by Ho’s institute, drug-resistant HIV is now commonplace: Nearly 30 percent of newly diagnosed HIV cases are resistant to at least one AIDS drug, and 11 percent are resistant to drugs in two or more drug classes.

In much of the criticism, there was an undercurrent of resentment toward Ho. Many saw the announcement as grandstanding. Michael Petrelis, an AIDS activist and blogger from San Francisco, fanned the flames with revelations about Ho’s links to Frieden (who sits on the Aaron Diamond Board of Directors) and the San Francisco laboratory that does the resistance testing, ViroLogic (as a scientific adviser, he receives a stipend and stock options). “I’m not saying any of that is wrong, or undermines the concern that Ho or others have about this mutant strain. I’m saying, we should know these things as we consider this case. That’s all I’m asking for: Give us all of the facts.” (In the interest of full disclosure, I should say that I also have some relevant history—I am a volunteer fund-raiser for Housing Works, the AIDS services agency that has been critical of Frieden, and I’m friendly with some of the players—including Frieden’s press spokeswoman.)

“I think it is only a couple individuals working really hard to spread bad news about us,” Ho says. “Whenever there is some news surrounding me or our institution, the usual suspects emerge—it’s not surprising to me.”

While Ho was contending with this backlash, his deputy Marty Markowitz surprised the February 15 New York meeting with a lecture stridently defending his superiority and referring to himself in the third person. “This is not for amateurs,” he said at one point, in response to a question. “You are arguing the … you are taking the doubting-Thomas point of view. However, you must also yield to the expertise of people who do know better.”

“You want to generate demand,” says Frieden. “You want people to think, Oh, I just had unsafe sex a couple of weeks ago … I should see my doctor.”

It was true that a kind of circuslike atmosphere was developing, with a laboratory in San Diego saying it had found a match there (not true, according to Frieden). South Park did an episode featuring a supervirus. And a doctor in Connecticut claimed he was treating the couple that infected Markowitz’s patient in the first place. “My guys were at the West Side Club on the weekend in question,” Dr. Gary Blick, a longtime AIDS practitioner based in Norwalk, told me. “The timing fits.” Blick says Frieden tried to keep him from going public with his findings, but he sent out a press release anyway. “I felt obligated before the Black Party [a vast annual party, held this year at Roseland] to give a message about this transmission.”

On March 29, Frieden announced the conclusion of the detective phase of his investigation. More than a dozen sexual contacts of the New York patient’s have been interviewed, and thousands of blood samples have been retested. But the investigation failed to find an original source for this viral strain, nor did it locate anybody who might have contracted it from the New York patient. Frieden has ordered further tests on about ten additional mutated strains that surfaced in his investigation, but for now it seems his worst fears haven’t come to pass. He hastens to say that he is relieved by this, not disappointed. And he has no second thoughts about going public. “The role of public health is to prevent outbreaks, not to describe them,” he says.

The problem, however, is one of crying wolf—the alarm gets harder and harder to hear. Despite the spike in doctor visits, the gay community apparently hasn’t changed course. Condoms are no more widely available at gay meeting places; drug use was just as prevalent at the Black Party as in previous years.

On one level, the case is a cautionary tale about the dangers of meth, unprotected sex, and complacency. And the mythological trappings surrounding the supervirus feed into that very sense of complacency. The introspection that rose up around the early epidemic has given way to what Dan Carlson, co-founder of the HIV Forum, calls a “culture of disease,” in which HIV is now accepted as an intractable reality. “Whether there’s a dangerous new virus among us or not, we need to talk about what HIV means to us,” Carlson says. “Why are we so skittish or afraid to talk about the issues that lead us to have unsafe sex? Do we talk about the decisions we make that put us at risk? We have a lot of work to do.”

And where does that leave Patient Zero? “It’s not a walk in the park,” Mullen says. “He’s taking a lot of drugs”—his regimen involves two daily injections—“and there are toxicities. He was short of breath for some time. But he’s responding to medications.” And he’s back at work.

If he continues his slow return to health, he may be allowed to fade into the ranks of the 110,000 New Yorkers who live every day with HIV without causing anybody alarm. But a 39-year-old veteran of AIDS scare stories named Hush McDowell wonders if that’s possible. In 1998, McDowell made global news as the first known person to catch multiple-drug-resistant HIV—and the last one responsible for unleashing the phrase “superbug” in the press.

“I feel awful for him,” says McDowell. “Maybe he’s able to ignore the press and focus on his care, but I never was.” These days, McDowell is doing well on medication, and he lives far from the media’s glare, tending bees on a farm in Tennessee. “Best thing I ever did,” he says.