Johnny Depp made his name on 21 Jump Street, playing a cop who passes for a high-schooler, and he’s hovered between boy and man ever since. It’s notable that, after all these years, he’s never asked us to call him John. Instead, he’s Edward Scissorhands, the childlike quasi-mute; he’s Sam of Benny & Joon; he’s Gilbert Grape, the devoted son who can’t leave home, suffocated by an obese and demanding mother. His new role, as Peter Pan author J. M. Barrie in Finding Neverland, is right in his wheelhouse: No other actor seems better equipped to play a man fixated on, and trapped by, perennial youth.

But if the role is appropriate, there’s something unsettling about Depp’s career trajectory, which is starting to look like the flight path of a boomerang. He’s long been Hollywood’s prodigal son, who took his inheritance of celebrity and bolted the kingdom, heading first for the art house and, eventually, to France. Then last year, he earned an improbable, welcome-to-the-club Best Actor nomination for his flouncing role as Captain Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean. With Neverland—the most respectable of vehicles, a reverential biopic—Hollywood’s greeting his return with welcoming arms: Son, you’ve become a leading man. There are even whispers of an Oscar, the industry’s version of a bar mitzvah. Never mind that Depp signed on for the film five years ago, long before his Pirates career spike and the consequent salary bump. (His new asking price of $20 million is larger than Neverland’s budget.) In Hollywood, coincidental facts have a way of cohering into a convenient plotline, and this one is neatly laid out. It’s the legitimization of Johnny Depp—a plot his fans can only hope will be thwarted.

Depp’s never been an actor of startling range, but he’s always brought a wide-eyed thoughtfulness to odd and interesting films like Dead Man and Ed Wood. Since jumping off the teen-idol track, his career’s been admirably eccentric—both the offbeat projects he’s pursued and his off-kilter performances in straight-up thrillers. (In fact, his choices are often so bracingly kooky that they seem a product of his own boredom, as though he’s reminding us just how tedious mainstream movies can be, even the ones he’s in.) He’s become an anti-action hero: He specializes in meek souls and naïfs, roughed up by the world. In both Nick of Time and Dead Man, he played ledger-clutching accountants, those clichés of timidity, bullied by cruel circumstance into becoming reluctant killers. Even Jack Sparrow, for all his posturing, was all bluster and no grit, with a side order of mascara.

And as a celebrity, Depp’s shown a genuine disdain for the pinup lifestyle that seemed his birthright. (After 21 Jump Street, he described the teenybopper magazines that lined up to put him in the cover: “What magazines?” Depp said. “Dream! Teen Poop! Teen Piss! Teen Shit!”) For his first lead film role, he buddied up with John Waters for the teen-idol parody Cry-Baby. He turned down Speed and Titanic to work with Terry Gilliam and Jim Jarmusch. This, too, is a kind of careerism, and he hasn’t exactly been living hand-to-mouth. But Depp has always lent his fame to movies he’d actually want to sit down and watch. If nothing else, he’s put the lie to the half-assed excuses of other pretty-boy leading men, who serve up dud after dud, then shrug as though they never had a choice.

Depp has always seemed too special an actor to become a true leading man. His tenderfoot good looks and bad-boy lifestyle embodied a fantasy: He, too, is the boy who never grew up.

Hollywood seemed stung by this bald rebuke of stardom—so much so that it even supported, for a time, the career of Skeet Ulrich, whose primary attribute is that he looks exactly like Johnny Depp. The hosannas that greeted Depp’s turn as Sparrow—a fun bit of contrarian mischief in a blockbuster based on an amusement-park ride—sounded not so much like long-suppressed affection but like an industrywide cheer at the unearthing of a bankable star. But Neverland may be a deceptive breakthrough: The role may help his career, but it suggests a threat to his immensely valuable niche in our culture.

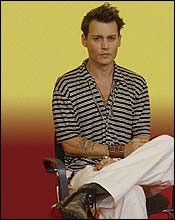

Depp has always seemed too special an actor to become a true leading man. His tenderfoot good looks and bad-boy lifestyle (the trashed hotels; the gorgeous women; the declarative tattoos, amended after heartbreak) embodied a fantasy: He, too, is the boy who never has to grow up. He’s the brooding high-school rebel who, rather than losing his hair and buying a car dealership, just goes on brooding and rebelling. He’s dodged grown-up responsibility, but not adult sexuality—he’s Peter Pan with pheremones.

In fact, decked out in his leather and stubble and rings, Depp’s always looked less like a movie star than a rock star—or, at least, our fairy-tale vision of a rock star. He never grows old. He looks essentially the same as he did in Cry-Baby: a little more gaunt, maybe, as though five years had passed, not fifteen. He famously modeled his Jack Sparrow antics on Keith Richards, but when Richards was Depp’s age, he wore his every excess carved in the creases on his face. In contrast, Depp looks Dorian Gray–fresh.

This forever-young appeal has sustained Depp for two decades, informing his performances and seducing his fans. His followers adore him, wanting to nurture him and have sex with him, though not in that order. Which is why his role as J. M. Barrie is both fitting and discomfiting. Barrie was a different kind of man-boy; he idealized, even fetishized, a pre-sexual innocence. Neverland’s been criticized for glossing over less-savory elements of Barrie’s biography, including suspicions of pedophilia. In defense of the film, Barrie biographer Andrew Birkin has countered, “Barrie harbored no lust for man, woman, child, or beast. Barrie was essentially asexual, clearly impotent.” No lust? Asexual? Impotent? Is that how we want to see Johnny Depp? In the preview for Neverland, we’re treated to him telling a young boy, “You can visit Neverland anytime you like … just believe.” It’s not hard, given this twinkly turn of events, to imagine him morphing slowly into Robin Williams.

Depp has two other movies in the pipeline: In one, he plays Willy Wonka, another man preoccupied with children; in the other, The Libertine, he’ll play the depraved Earl of Rochester. It will be heartening to see Depp as a sex fiend, and one not obsessed with little boys. Willy Wonka is a trickier prospect: One can only hope the role will emphasize the weird over the twee, and that the star’s new high-profile status won’t undermine his willingness to risk. Consider the example of Nicolas Cage, Depp’s old friend and the guy who got him into acting in the first place. Cage, too, was once a celebrated, offbeat maverick. Then he won an Academy Award. Now interesting films like Adaptation are the exception on his résumé, wedged in between The Rock, Con Air, and the forthcoming National Treasure—a thriller about a man who finds a treasure map on the flip side of the Declaration of Independence. On one side treasure, on the other independence: Maybe that’s a movie Depp could have starred in after all.