To understand Forest Whitaker, you might start with the fact that he finds sympathy for every character he plays, even Idi Amin. It helps that he’s just finished a film, The Last King of Scotland, for which he spent months getting inside the Ugandan dictator’s skin. He taught himself Swahili. He learned to play the accordion, as Amin did. He traveled to Uganda and interviewed Amin’s former generals and relatives. “He’s a very complicated man,” says Whitaker. “He was responsible for major atrocities, but he also reshaped opportunities for people in his country. He was a person who was colonized, and he stood up to colonialism. And he was demonized for many things, but partly for standing up.”

In fact, when Whitaker is talking, it sometimes sounds like he has more sympathy for his characters than he does for himself. It’s not that he beats himself up. But he feels that he’s been drifting a bit. So this year, he looked to stoke his creative fire. As part of that project, he took his first-ever ongoing TV role, as an Internal Affairs detective named Jon Kavanaugh on FX’s The Shield. The police drama, now in its fifth season, was inspired by L.A.’s Rampart scandal, in which a real-life group of cops was revealed to be operating like a kind of rogue street gang. The show stars Michael Chiklis as Vic Mackey, an often-brutal and frequently unethical but inarguably effective cop. Last year, the series was invigorated by Glenn Close’s season-long cameo as Mackey’s wary but supportive captain. This season, creator Shawn Ryan pursued Whitaker to come in as a different kind of foil: He’s Mackey’s own Inspector Javert.

For this role, Whitaker, who’s 44, hasn’t had to immerse himself in a foreign culture or learn a new language. He grew up in South Central L.A., so he has his own visceral feelings about the tactics of dirty cops like Mackey. “The way I look at police officers—” he says, then stops. “Okay, I do recognize the necessity of police officers in this society. And I know there are good cops. But I also come from a background where, on my street, cops killed people. Relatives of mine were killed by police officers. Having been someone who’s been thrown across the hood of a car—in life! Not in movies! Just growing up!—I know what police officers are capable of.”

“I do recognize the necessity of police officers in this society. But on my street, cops killed people. Relatives of mine were killed by police officers.”

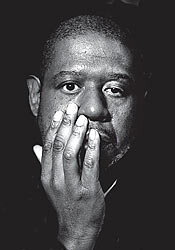

Two years ago, Whitaker had come to such a career crisis that he decided to shut down his successful production company, Spirit Dance. “I was trying to figure out what I was saying. I needed to retreat for a moment into silence,” he says. “I started to question what kind of stories I was putting out into the universe.” This is how Whitaker talks: He’s interested in, even consumed by, questions of spiritual responsibility. Sometimes he’ll digress, then stop himself and laugh and apologize for sounding corny. But Whitaker’s great strength onscreen has always been his ability to play off the tension between his appearance (six feet two; a hulking physique; the one eye that droops, slightly offset from the other) and his serene spiritual bearing. This is, after all, a guy who grew up as a heavily recruited high-school football star while also studying opera. He went to college on a sports scholarship and, after a back injury, switched to singing, then acting, eventually graduating from USC’s theater program.

He’s enjoyed a prodigious career since, marked by a transcendent turn as Charlie Parker in Clint Eastwood’s 1988 jazz biopic, Bird, and a devastating performance as a doomed British soldier in The Crying Game that left some fans convinced he was from the U.K. (He was born in Texas.) To many, his definitive role was the becalmed pigeon-raising, Samurai-code-following Mafia hit man in Jim Jarmusch’s 1999 film Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai. In between, he’s made a good living by playing flat characters in pulpy thrillers, such as his remorseful crook Burnham in Panic Room, and lending them a distinct and soulful grandeur they often don’t deserve. Of Burnham he says, “He broke into a home. He put gas in a room with a mother and a child. So I’m always fascinated by how many people wanted that character to get away.”

He also expanded into directing, making his debut with a grim film about inner-city gun violence, Strapped, for HBO in 1993. His next movie, Waiting to Exhale, was a smooth buppie drama, but it was nonetheless welcomed as the kind of African-American story that was rarely being told, namely, one that doesn’t involve thugs, guns, or drugs.

But it’s easy to see why, in recent years, Whitaker felt that his focus was slipping. He took parts, such as the crisis-defusing cop in Phone Booth, that were dim echoes of roles he’d played a dozen times before. And he can’t have been heartened by donning dreadlocks and alien makeup to tromp around behind John Travolta in Battlefield Earth. The most recent film he directed, 2004’s First Daughter, with Katie Holmes, was not only a harmless comedy about the president’s daughter falling in love, but it was the second harmless First-Daughter-falls-in-love comedy (after Chasing Liberty) to come out that year.

“I was losing my way,” he says now. “I wanted to find something that had to be said. Something that lived in the more complicated realm of people’s feelings and relationships—things which I’ve possibly expressed more strongly in my acting work.” And it’s true: As an actor, he’s always been particularly good at characters who are torn by contrary tendencies—whether it’s a dictator who tries to liberate his people through genocide or a cop whose livelihood is bringing down other cops. “As human beings, we all have reasons for our behavior. There may be people who have certain physiological issues that dictate why they make certain choices,” he says—and here he sounds like he could just as easily be talking about himself. “On the whole, though, I think we’re dictated by our structure, our past, our environment, our culture. So once you understand the patterns that shape a person, how can you not find sympathy?”

Having been so rigorous about employing this approach with his characters this way, he’s now learning to apply that same philosophy to himself. And he’s feeling a bit better these days. “I’ve done a couple of projects where I feel like my work is progressing,” he says. “That I was maybe becoming a better actor. Because I’ve been trying to get better.” He’s planning to open a new production company, under a new name, this March. He’s proud of his Idi Amin role, and he’s just finished Mary, with director Abel Ferrara, in which he plays a TV journalist who seeks redemption by making a documentary about the life of Christ. Whitaker’s new approach has proved redemptive for him as well, both in his roles and his bolstered sense of self. “I’m always trying to find a connecting factor with everything else and everyone else,” he says. “As a result, even when I play murderers or hit men or whomever, people tend to find some empathy for them. Because I look for that thing. And people can see that, gleaming inside my mind.”