Woody Allen’s Melinda and Melinda begins as a labored variation on My Dinner With Andre: Wallace Shawn parries with a dining companion (Larry Pine) about the nature of comedy and tragedy. It then divides into two separate, alternating plots—a flat comedy and a puffed-up drama. It’s as though, after all these years of alternating between the two forms (chuckle at Radio Days and he’ll slap you upside the head with the dead fish of September), Allen decided to make a mix-and-match picture. In theory, it’s an intriguing gimmick, but in execution, this double feature of a film is too genteel by half.

In the “comedy” section, the title character, Melinda, played by the Australian actress Radha Mitchell, is an American ditz, a visitor who shows up at the New York apartment of married couple Amanda Peet and Will Ferrell. They’re throwing a dinner party with a purpose: Peet, as Susan, a film director, is trying to drum up financing for a movie, while Ferrell, as husband Hobie, hopes to land a big role in the film. Melinda’s alarming arrival—she claims to have recently downed 28 sleeping pills—throws off the rhythm of the evening, and pretty soon Hobie has fallen for this troubled but lovely mess of a girl.

The “tragedy” section has Melinda arriving at the loft of an old friend (this one played by Chloë Sevigny) and her out-of-work actor-husband (Jonny Lee Miller). Strung out on pills and cigarettes, severely depressed by a recent divorce, this Melinda is a neurotic emergency who annoys the husband but makes Sevigny’s character realize just how unhappy she herself is.

The movie switches back and forth between the two tales, often to its narrative detriment—just when you’ve mustered a little curiosity about how Tragic Melinda is faring, Allen pushes us back to Comic Melinda, and into a plot where we’re supposed to guffaw at the idea that Ferrell, as an assiduously dense doofus-thespian, thinks it’s a bright idea to give every character he plays a limp. The movie’s biggest laugh line is in the trailer, when an exasperated Peet says to Ferrell in mid-bad-marriage squabble, “Of course we communicate—now could we not talk about it?”

Neither version of Melinda, despite Mitchell’s game try at making them distinctive beyond their different hairdos, is funny or tragic enough to fully engage us; there’s no opportunity for an audience to be moved. Allen is onto something interesting when he has Jonny Lee Miller remark that “life is all about networking”; who is a greater expert on gatherings of Manhattan intellectuals? In contrast to the yearning artists Allen has sketched in the past, Miller’s and Sevigny’s characters are at once more cynical and more desperate, and it would be fascinating to see how a shrewd pro like Allen explores this Gen-X/Y cliché from his older, savvy perspective: Is the present generation more honest or more devious about their avariciousness? But, alas, he lets the notion drop away. And it’s become sad to see Allen trying to lower his aging audience demo by casting actors who’ll appeal to “the kids”—Jason Biggs and Jimmy Fallon in the thudding Anything Else (2003), and now Will Ferrell. This is the first time onscreen that Ferrell, Saturday Night Live’s most protean, fearless male cast member since the late Phil Hartman, looks uncomfortable and hemmed in. Ferrell can’t help it: The moment he agreed to be cast as the latest surrogate character for Allen himself, as Kenneth Branagh was in Celebrity (1998), he was doomed. Doomed, that is, to recite punch lines whose rhythms Allen has written for his own unmistakable halting tone and prissy-man image. Thus, when asked what he does for exercise, Ferrell’s Hobie replies, “Tiddlywinks and an occasional anxiety attack.” The line fails on three levels simultaneously. First, tiddlywinks is a game by now so old-fashioned that baby-boomers may strain to place the reference (it’s not something a modern dunderhead like Hobie would say). Plus, the barrel-chested Ferrell is far too hale to be believably unathletic. And finally, this is the umpteenth, watered-down variation on the panicky-man joke Allen has been delivering since he first scurried out onto the stage of The Ed Sullivan Show.

The press kit that accompanies Melinda is larded with the usual gush from the cast about what an honor it is to be chosen by Allen (“I was so awed by the fact that Woody would even ask me”; “First I had to get over the headline of ‘Being in a Woody Allen Movie’ ”). It’s both touching and baffling. Yes, Allen has given us Annie Hall, Hannah and Her Sisters, a delightful trifle like Manhattan Murder Mystery, and the gratifyingly tough-minded Deconstructing Harry, which tapped into the bracing vulgarity of his early comedies. But when are we going to get a generation of actors who will finally decline to succumb to The Woody Mystique, and refuse to accept a proffered role without first deciding whether the entire damn project is worthwhile?

Melinda and Melinda

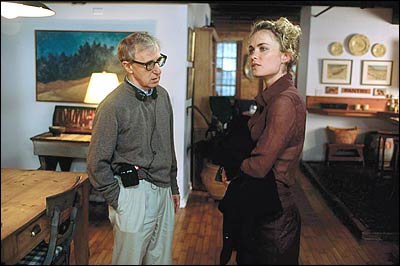

Directed by Woody Allen.

Fox Searchlight. PG-13.

Get Showtimes