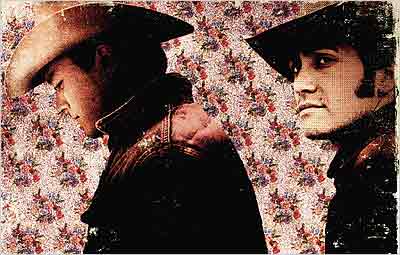

For all its advance publicity—Newsweek declared it “a must-see for film lovers” and Time averred that it “has generated lip-smacking advance criticism” (that’s intended as praise, by the way; who was asleep at the copydesk when that phrase dribbled in?)—I think large portions of the first wave of audiences for Brokeback Mountain are going to be startled, some rattled, some elated, by the sexual and romantic relationship between the two cowboys played by Jake Gyllenhaal and Heath Ledger. When, a half-hour into the film, Gyllenhaal’s Jack Twist and Ledger’s Ennis Del Mar, both drunk, cold, and lonely on a remote Wyoming campsite, fold around each other and commence an act of sex that manages to be both rough and tender, romantically intimate and lustily intense, Brokeback Mountain achieves its own early climax: You either buy into this tale of men in love or you join the ranks of those who’ve been snickering during the movie’s prerelease trailers, and who can be divided into the insecure, the idiots, or the insecure idiots.

The remarkable thing director Ang Lee has done is to have made a film that remains firmly in the Western genre while never retreating from its portrayal of a tragic love story. We’ve long had the so-called revisionist Western, usually meant as a cowboy story that contains modern themes or metaphors and dramatizations of social change. In Hud (1963), Paul Newman and director Martin Ritt took Larry McMurtry’s novel Horseman, Pass By and used it to turn the contemporary cowboy into a heel, a cad who could seduce you and still give you the creeps. In The Wild Bunch (1969), Sam Peckinpah explored the effects of violence in a manner that couldn’t help but remind viewers of the then-contemporary bloody morass in Vietnam.

Similarly, director Lee, working from a story by E. Annie Proulx and a script by McMurtry and Diana Ossana, pushes the Western to accommodate explicit sexuality. Lee crafts a meditation on that most potent of dramatic subjects—thwarted love—without jettisoning the trappings that make the genre satisfying in the first place. It’s wonderful to watch Jack and Ennis lope along on horseback, hired hands herding sheep in the gorgeous blue-green Wyoming mountains. When we first meet them, the pair are young bucks who yank at the brims of their carefully dented cowboy hats and poke their booted heels into the ground, staring at their toes while mumbling greetings or small questions: It’s as though they’re playing out the ritual of shy-guy courtship after having seen too many Gary Cooper movies.

After showing their initial idyll in the mountains, Brokeback does to its heroes what no movie cowboy wants to have happen: Things change in the world around them. They complete the sheepherding and rejoin society. Ennis mumbles, “This is a one-shot thing we got goin’ on here.” Jack mumbles back, “Ain’t nobody’s business but ours.” They separate and years go by; they marry—Jack to a luminous brat (the glowingly smart Anne Hathaway), Ennis to an earnest gal who adores him (the amazingly subtle Michelle Williams)—but these are fundamentally loveless unions: quiet, piercing betrayals. Jack and Ennis get together every so often, for private “fishing trips” that forge their love and doom it at the same time. The sneaking around and the frustration caused by everything and everyone around them eats away at them when they’re apart.

The movie tells us that when pure, strong love gets tamped down and extinguished like a cigarette butt crushed under a boot heel, the result is as immoral and deadly as getting shot in the back. Jack and Ennis are doubly cursed. They can’t be together, and they can’t abide by the code of honor to which men in Westerns aspire, because that code doesn’t allow for these particular emotions. If I’m making it sound as though Brokeback Mountain is a downer, it’s actually a serious piece of art in which great joy can be taken in witnessing the small-miracle performances of Ledger (so eloquent in his mute despair) and Gyllenhaal (so meticulously agonized by his daily compromises). Ang Lee conveys maddening delirium rendered in the way one man’s eyes gaze at another’s, and then look away, and the looking-away amounts to the murder of two souls as surely as if they’d drawn guns and hit each other in the heart.

Brokeback Mountain

Directed by

Ang Lee.

Focus Features.

Rated R.