What must Kate Winslet think? As one half of the romantic team in the biggest-grossing movie of all time, she might reasonably expect something like hysteria surrounding her next screen appearance. Leonardo DiCaprio and his posse, after all, are trailed by the press from here to Timbuktu; his upcoming movie projects, his salary, his main squeezes, are examined with the kind of scrutiny normally reserved only for the chief executive of our land. Meanwhile, here’s Winslet in a new movie, Hideous Kinky, playing an English mother with her two daughters in Morocco – and no tom-toms are sounded. It’s as if the success of Titanic was linked in the popular imagination entirely to DiCaprio, with Winslet the lucky stiff who just happened to be cast alongside him. The deafening near-silence in the press surrounding the post-TitanicWinslet – except, tellingly, for the snipes about her “weight problem” – is a slap in the face to an accomplished actress.

Standards of beauty tend to go in and out of phase, and what I fear may soon be upon us is another stultifying cycle of movie-star-looking movie stars: Call it the Gwyneth Syndrome. We’ve been down this road before. In the Grace Kelly fifties, the height of attractiveness was how well you looked in a tiara. The waxworks handsomeness and hyperprettiness of many of the Hollywood screen actors of the sixties – the Doris Day-Rock Hudson era – was a big reason why films from that period were so bland. I have nothing against movie-star beauty, but is it asking too much for a little something to be going on behind the stars’ eyes? One of the most exciting developments in movies over the past few decades has been the opening-up of acting – of stardom – to the less-than-picture-perfect types. It enlarges the range of experience on the screen. (The great movies of the early seventies are unthinkable without the collection of unruly faces they introduced.) How depressing – how patrician – it would be to return to a celebration of glossy, whittled physical perfection.

In the current pop-celeb derby, Kate Winslet loses out to Gwyneth Paltrow’s tiara twinkle. This despite the fact that, aside from Titanic,where she managed to hold her own with the boat, Winslet’s work in Heavenly Creaturesand Sense and Sensibilityand Judeand Hamletshow her off to be the better actress. Not to mention being the one with the authentic British accent. But authenticity may not be as valued these days as the sparkling counterfeit, and Winslet, unless James Cameron cooks up some kind of DiCaprio-ized prequel to Titanic,is probably slated for an unglitzy career in which she is merely excellent.

Her new film is a no-stars, non-Hollywood, medium-budget affair. It seems an odd follow-up to Titanic – but that may be the point. Hideous Kinkyis the un-Titanic. It’s far from great, but it gives Winslet a chance to explore different sides of her talent. (Her next film, due at the end of the year, co-stars Harvey Keitel and is directed by Jane Campion; I hope this doesn’t mean she’ll be playing a mute.) In our megabucks movie climate, it takes courage for a hot commodity to refrain from inserting herself into the next empty blockbuster; but what may take more courage in the long run is trying to extend one’s craft. You can, after all, be just as unadventurous in an empty small movie as in an empty big one.

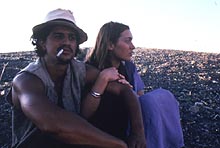

In Hideous Kinky,set in 1972, Winslet is playing Julia, who has left London with her two small daughters (Carrie Mullan and Bella Riza) for the all-spice exotica of Marrakech. Surviving tenuously on checks from her British ex-lover, a playboy poet and the father of her girls, Julia camps out in a hotel peopled by prostitutes who filch her undies and then contemptuously swagger about in them in full view of her. For her daughters, Marrakech is an Arabian Nightsadventure, but Julia seeks enlightenment from a Sufi in Algeria. To reach him, she drags her kids through escapades in a remote mountain village, and then a Moorish villa occupied by European émigrés who seem to have stepped out of a Paul Bowles story. (Their host is played by Pierre Clémenti, best remembered as the leather-jacketed john with steel-capped teeth in Buñuel’s Belle de Jour.) She takes up with a Moroccan acrobat (Saïd Taghmaoui) who keeps appearing and reappearing throughout the odyssey as a combination stud muffin and guardian angel.

Winslet captures the ways in which Julia’s allegiances are always in flux. She cares for her children, but she’s part child herself; she resents how being a mother breaks her own self-absorbed gaze. Gillies MacKinnon, directing from a script by Billy MacKinnon based on a novel by Esther Freud, doesn’t soft-pedal the irresponsibility behind Julia’s wanderlust, and yet you can’t entirely blame her. The people and the landscape and its colorations – which at times resemble Matisse’s Moroccan paintings – pull us in, too. Julia’s children, who are under no illusion that they are on the road to salvation, are more clearheaded than she is. One of the movie’s continuing jokes is that Julia becomes more childlike as her daughters come to resemble miniature Englishwomen of breeding. A sensualist who has eroticized her own spiritual quest, Julia’s the apotheosis of hippieness.

It augurs well for the long-term integrity of her career that Winslet in this movie doesn’t try to ingratiate herself with the audience; a role like this needs to be approached honestly – with an appreciation for the ways in which wantonness can fog our good sense. Near the end of her quest, Julia says, “I want to know the truth,” but she doesn’t, really. She’s just looking for a more aromatic species of lie.