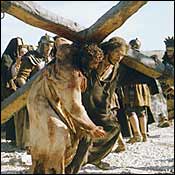

Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ bears the same relation to other biblical epics as a charnel house does to your local deli. To say that it’s the bloodiest story ever told is an understatement; rarely has so much red stuff flowed in any movie. To some extent, I was prepared: Gibson’s Braveheart, in which he played thirteenth-century Scottish rebel William Wallace, ends with Wallace’s interminably tortuous demise on the rack—a warm-up, both emotionally and stylistically, for Christ’s martyrdom in The Passion. But, before the Crucifixion, we are treated, in fetishistic detail, to nearly two hours of scourging and flaying. By the time Jesus is nailed to the Cross, you may be too numb to care. No doubt Gibson intends all this gore as a testament to his uncompromising faith; he’s compelled to show us the horrors that other Christ-themed movies downplay. But I didn’t leave The Passion—which is about the last twelve hours in the life of Jesus, with dialogue delivered in Latin and Aramaic—believing I had witnessed a movie made by a man of great spiritual gifts. Gibson’s fervor, it seems to me, belongs as much to the realm of sadomasochism as to Christian piety.

It isn’t just the violence that is overplayed. There is so much creepy-Gothic Sturm und Drang in The Passion that at times it seems as if Clive Barker should get credit for the story along with Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Jesus is played by James Caviezel, who looks like a bearded, beatific Sam Waterston before his wounds render him unrecognizable. In the film’s first scene, in Gethsemane, where Jesus has gone to pray after the Last Supper, we are introduced to a shape-shifting, androgynous Satan and a doomy, clamorous score more appropriate to Pirates of the Caribbean. After Jesus is brought before the Pharisees and accused by the high priest Caiaphas (Mattia Sbragia) of blasphemy for believing himself to be the Messiah, the movie becomes less Gothic and more like a religioso WrestleMania smackdown. The jeering Roman soldiers under the control of Pilate (Hristo Naumov Shopov), governor of Palestine, are so cartoonishly brutal that they seem to be firing themselves up to enter the steel cage. Big, broad strokes—that’s Gibson’s forte.

Pilate is the only character besides Jesus whom the film presents with any nuance; as PR for the prefect, The Passion could hardly be better. Going beyond what is written in the Gospels, not to mention what is in stark contrast to Roman histories of the era, this Pilate is torn about what to do with Jesus. Counseled by his wife (Claudia Gerini)—at one point, he asks her, “What is truth? Can you tell me?”—he tries to save Jesus from the Jewish mob; he even hands Jesus over to Herod (Luca de Dominicis) in the hope that the problem will just go away. This proves a dead end, since Herod, portrayed as a mincing queen, doesn’t take the bait. (“Work a little miracle for me?” he coyly asks the would-be Messiah.) It turns out that this powerful prefect has no choice but to accede to the wishes of Caiaphas and the other rabbis—even though it was they who served Pilate, who had sole power to execute. The way Gibson and his co-screenwriter, Benedict Fitzgerald, tell it, Jesus is maneuvered to the Cross by high priests who prey upon Pilate’s fear of Caesar’s retribution should rebellion break out. The Romans inflict unimaginable agonies upon Jesus, but behind it all is Caiaphas’s bland smirk: He doesn’t get his hands dirty. Caiaphas even shows up for the main event at Golgotha, presumably to keep an eye on things—a detail that somehow got by all four apostles.

Is The Passion the work of an anti-Semite? In the September 15, 2003, New Yorker, Gibson claimed that “modern secular Judaism wants to blame the Holocaust on the Catholic Church.” He belongs to a splinter sect of Catholicism that rejects the Second Vatican Council, which reconciled Christians and Jews and said that “the Jews should not be presented as rejected or accursed by God, as if this followed from the Holy Scriptures.”

The Passion is not about reconciliation. You might never get the idea from it that Pilate slaughtered Judeans by the thousands for sport. Still, as Passion plays go, the movie doesn’t fulfill one’s worst expectations. Gibson financed the $25 million film himself and is heavily promoting it as a vehicle for Christian outreach. He doesn’t turn the Romans into “fall goys” (in the immortal words of the late Dwight Macdonald). But he is also careful to plunk into the story various Jews who are sympathetic to Jesus, including a few dissenters in the high priests’ temple and a weeping young mother on the road to Golgotha.

Nevertheless, the engine of this movie is not passion but anger. When Gibson flashes back to the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus’ words about loving those who hate you come across as oddly hollow, since there is so much unmitigated hate in the movie. Even the Pietà frieze near the end is curiously unfeeling. The horrors in The Passion cry out for vengeance, just as they did in Gibson’s Mad Max and Lethal Weapon movies. The film ends with Christ’s Resurrection. Get thee behind me, Satan!

It is, of course, unfair to expect Mel Gibson to give us an artistic expression of the Passion on par with, say, Bach’s or Grünewald’s. And I (almost) prefer his bloodbath to the prim reverence of a movie like George Stevens’s The Greatest Story Ever Told, with cameos by everyone from John Wayne to Ed Wynn. But The Passion, as much because of its controversies as in spite of them, is likely to be seen all over the world by people thirsting for spiritual connection. The real damage will not, I think, be in the realm of Jewish-Christian relations, at least not in this country. Anti-Semites don’t need an excuse to be anti-Semites. The damage will be to those who come to believe that Gibson’s crimson tide, with its jacked-up excruciations, is synonymous with true religious feeling.