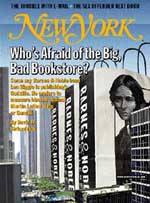

Leonard Riggio, the 58-year-old chairman and chief executive of Barnes & Noble, is on the phone trying to close a deal with the writer Toni Morrison. Most authors are eager to please Riggio, the head of the country’s biggest bookstore chain. But Morrison’s rare success – she has won both the Nobel Prize and the Oprah Winfrey seal of approval – gives her license to be stubborn. “Toni,” Riggio finally asks, “are you so rich now that you don’t care anymore?” Riggio himself is one of the richest people in the U.S. and well acquainted with the moral burdens of wealth and power. The success of his capacious, librarylike superstores has ironically made him the villain of the literary world – accused of breaking antitrust laws, closing down thousands of independent bookstores, bullying publishers, and flattening the literary landscape. A decade of criticism has battered his public image into a caricature: college dropout from Bensonhurst and swarthy, hotheaded philistine.

That portrayal wounds Riggio deeply. He sees himself as something else entirely: a man of high purpose, committed to art, literature, the best that has been thought and said. In fact, Riggio was trying to enlist Morrison not to hawk books but to read at the dedication of a new library for the Children’s Defense Fund’s campus in Clinton, Tennessee. Riggio had put up $1 million to build and stock it, and picked the artist Maya Lin, whose Vietnam Veterans Memorial he’d long admired, to design it. And he’d derailed the group’s plans to name the library after himself, suggesting instead that it be dedicated to Langston Hughes.

Riggio’s cajoling (and the promise of transportation onboard a Riggio-chartered jet) helped persuade Morrison to sign on, and she joined Hillary Clinton, Rita Dove, and Joyce Carol Oates on the event’s program. At the dedication, Riggio hobnobbed cheerfully with the assembled liberal activists, scholars, and writers, happy to be respected not only for his money and power but for his ideas. He opined to Maya Lin about the achievements of the artist Donald Judd and bantered with former New York City deputy mayor Bill Lynch about Al Sharpton’s “leadership qualities.” “This whole thing is wonderful,” Riggio said, leaving one panel discussion. “But what aggravates me is that there is no call to arms. I mean, what are we going to do about all this?”

Still, much as Riggio may like to devote his energies to “the movement,” as he calls it, he has a business to run. And as Barnes & Noble tries to catch up with Amazon.com in online bookselling, his public image as a greedy monopolist is beginning to catch up with him. Amazon.com’s preppy 35-year-old founder, Jeff Bezos, has beguiled the press and won the allegiance of trend-setting consumers by portraying his company as hip and innovative while casting Barnes & Noble as a predatory behemoth. “Goliath is always in range of a good slingshot,” Bezos (whose personal net worth is probably ten times that of Riggio) announced when Barnes & Noble agreed to acquire the distribution giant Ingram Book Group. In an irony not lost on Riggio, Bezos even teamed up with the small bookstores’ trade group to lobby antitrust regulators into opposing the acquisition. And so Riggio finds himself once again in the spotlight. While the book world is watching to see if Barnes & Noble can stage a comeback in the Internet bookselling business – he spun out his own Website, barnesandnoble.com, or bn.com, in an IPO last month – Riggio himself is waging a more personal struggle, to overcome his lingering image as a menace to literature.

Hi, I’m Lenny,” Riggio says, introducing himself in a voice that still carries a hint of the nasal “dese” and “doze” of his native borough. He is a short, dapper man, with a round face, a trim mustache, and a Mediterranean nose. It is the afternoon after the initial public offering of bn.com, and he is sizing up a giant cake in the shape of a B that’s been delivered to his office. “It’s kind of a letdown,” he says of the IPO experience. “It’s sort of like the day after Christmas. Some people get all excited, but, you know, I’ve done this a number of times now, and I am a little more even-keeled than that.”

Maintaining his composure wasn’t easy that week. In an apparent attempt to upstage Riggio’s IPO, Jeff Bezos had just announced that Amazon.com would begin discounting best-sellers 50 percent – forcing Riggio to match him. And the Federal Trade Commission’s staff said it would oppose his Ingram acquisition as anti-competitive. The news sent bn.com’s stock plunging below its offering price. But perhaps most galling to Riggio was an article in that month’s Wired magazine about bn.com.

“Whatever I say, they can always find a way to turn it into ‘the combative Len Riggio,’ ” he says. “What the press writes about me has nothing to do with who I am – it’s not even close!”

Amid the hectic preparations for the spin-off, Riggio found time to fire off a four-page point-by-point rebuttal to the Wired piece. The story “unnecessarily humiliated” him and his company, Riggio wrote, especially when it called his superstores “dastardly” and his mustache “an anachronism.” Nor was it fair to say that he terrorized the book business like a schoolyard bully; he is the one who feels beat up. “Bullies come disguised in many costumes,” he wrote to the magazine’s editor-in-chief. “Some even wear the garb of objective journalists.”

“You have to be pretty mean to say that kind of thing about another human being,” Riggio says plaintively. “But it seems like civility has been replaced with a clenched fist. From the things they write about me, you would think I wake up in the morning thinking about who I am going to kill. I wake up looking to do some good! We are selling books. We aren’t selling weapons of mass destruction. You go into a bookstore, you see Len Riggio’s life’s work, and you say, ‘Not a bad lifetime of work’; then you read this stuff, and you think that I am at war all the time! Twenty years ago, we opened a new bookstore at Columbia University, and the Times wrote death of a bookstore. And it’s never stopped!”

Riggio once called New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. to complain personally about a conspicuous error, and then followed up the Times’ correction with a further clarification of his own in the form of a full-page ad. “How can you do a full-page story and then a one-sentence correction?” Riggio says.

Some of Riggio’s Italian-American friends feel he is the victim of ethnic bias in the publishing industry. “I went into those little shops, and I was badly treated,” says the author Gay Talese. “They were stuffy and intimidating. But Len Riggio is the name now, this devouring demon eating up all these wonderful neighborhood bookshops.”

Nora Ephron used the conflict between the superstores and the independents as the basis for her 1998 movie You’ve Got Mail. As she prepared for production, Kurt Andersen (the novelist and former editor of this magazine) and Riggio’s friend Tibor Kalman helped broker a meeting between Riggio and Ephron at a small dinner at the downtown restaurant Verbena. Ephron hoped Riggio would let the film crew shoot at a Barnes & Noble store, but he worried the movie was a thinly veiled and critical portrait of himself. “Believe me,” she told him at the end of the meal, “if I had wanted to model it after you, I would have cast John Travolta instead of Tom Hanks.”

Riggio laughed but declined to cooperate. “He isn’t stupid,” Ephron says. “He is very sensitive, and very defensive about the impact of his stores. You don’t even have to say anything and he’s already defending himself.”

Riggio’s superstores, for better or worse, have changed the book business as profoundly as anything since the advent of the paperback. The company’s more than 520 superstores and 465 smaller B. Dalton stores now sell nearly one in every eight trade books sold in the U.S. Barnes & Noble has nearly a quarter of the bookstore market, where almost all literary fiction and serious nonfiction is sold.

For independent bookstores, the facts are grim. Despite Barnes & Noble’s argument that its superstores have expanded the market for books, the number of copies of adult trade books sold in the U.S. has grown in the past ten years at a rate of less than one percent annually. During that time, the number of Barnes & Noble superstores has grown from a handful to more than 500, tripling the amount of shelf space devoted to selling books in some markets. Unlike mall chains, Barnes & Noble and its rival Borders invaded the urban centers and college towns – the independents’ turf – and small stores folded in droves. Membership in the independent stores’ American Booksellers Association fell from 5,500 in 1994 to 3,400 in 1999.

“It seems like civility has been replaced with a clenched fist. From the things they write about me, you would think I wake up in the morning thinking about who I am going to kill.”

Barnes & Noble’s phenomenal growth has put publishers in a tight spot and hastened their consolidation. Like suppliers in many other industries, publishers were accustomed to being much bigger than the stores that sold their books, giving publishers the upper hand when they negotiated contracts with booksellers over variables like wholesale book prices and who pays shipping costs. Now, however, the power belongs to the giant retailers. “The advent of the superstores makes publishing much riskier, because the buyers at one of the giant chains have a big say in the initial success of a book,” says David Rosenthal, publisher of Simon & Schuster’s trade-books division. And book publishers’ race to merge, partly to match the booksellers’ clout, gives just a few people ever more say over what books get pushed.

“If you are trying to take a big position on a book and you can’t get the chains to support you, you really have a problem,” says Morgan Entrekin, publisher of Grove/Atlantic. “But I tell you, it is going to be very hard to get publishers to speak frankly about this. Whatever we say about the chains or the independents, somebody we have to do business with is not going to like it.”

Privately, many publishers complain in more colorful terms about Barnes & Noble’s growing clout, and their resentment has focused with particular venom on an arrangement known as cooperative advertising. (“Blackmail” says one editor; “whorehouse work,” says another.) Since the seventies, mall-based chain bookstores and a handful of big independents have charged publishers complicated fees to include their titles in catalogues, to place their books in prominent store locations, or to feature the titles in advertisements. In the nineties, when Barnes & Noble and Borders began to roll out superstores across the country, cooperative advertising became big news.

Publishers began leaking to reporters Barnes & Noble’s marketing-program price lists, and prices were eye-catching. Today prices run as high as $18,000 to place a title in Barnes & Noble newspaper ads across the country. Placement in a New York Times ad and on a prominent store table for two weeks can cost as much as $10,000. But most serious or literary books are usually backed by less than $15,000 for author tours, advertisements, and all other publicity.

Riggio dismisses the gripes out of hand. “The creeps should never give that stuff out,” he says. “It is just the publishers blaming us as a scapegoat when they feel the pinch of their own inept business practices. Nobody is bribing us.”

He insists that publishers don’t pay for placement, because Barnes & Noble picks the books to promote, albeit in consultation with the publishers. The charges come out of a pool based on an extra 3 or 4 percent discount off the wholesale book price from each publisher, and the retailer accounts for the money later.

The struggling independents have taken their case to the courts. In 1994, the independent store owners’ American Booksellers Association sued several of the biggest publishers for providing unfair subsidies to the chains, and the publishers settled by agreeing to make “co-op money” equally available to single stores and chains. The ABA is now suing Barnes & Noble and the other superstore chains, alleging that they find ways to skirt the law, squeezing publishers for financial perks like better payment terms and lower delivery costs.

Riggio vehemently denies the ABA’s charges, noting that the same co-op deals and discounts are available to every store and that the basic terms haven’t changed in years. “We have to have a lawyer in the room whenever we talk to a publisher!” he says. The superstores’ advantage, according to Riggio, is in spreading their overhead over more sales, not in gouging publishers. Every bookstore has to employ book buyers, but Barnes & Noble can hire one central staff to fill its 520 superstores. Economies in advertising costs are an even bigger advantage. Small stores can’t afford to pay as much as $40,000 for a full-page ad in a big-city paper, but superstores can, especially if several are clustered together in the same media market.

But to others, those economies of scale are exactly what is dangerous about the superstores: Decisions about how many copies to stock, which titles to advertise, and where to place books in stores are inevitably more centralized than ever before. “The books that are on the shortlist are on the shortlist everywhere,” says Cornell University economist Robert Frank, author of The Winner-Take-All Society. “That puts a lot of pressure toward concentrating sales on a smaller number of titles, and the vastness of the stores makes the issue of where the book is displayed even more important.” The superstores have applied to the book business a dynamic now common in markets for movies and music too, he says. The few titles that “break out” soar higher than ever, but the rest fall behind.

“The rich are getting richer and the poor poorer,” confirms Roger Straus, of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. “There is no question that the superstores have made it possible for the best-sellers to be bigger than ever. That is why we sold 750,000 copies of Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities, and 1.1 million of A Man in Full. The downside is that with small books, it doesn’t do any good, and maybe it does some harm. They don’t get attention, and they are returned in a hurry.”

Copies of the top 30 best-selling books in fiction and nonfiction rose from 7 percent of U.S. hardcover-book sales in 1986 to 13 percent a decade later. Riggio often points out that less than 4 percent of superstore book revenue comes from Times best-sellers. But the best-sellers’ rising share of the hardcover market still suggests a concentration of sales. According to Barnes & Noble merchandising executives, just 100 of the more than 45,000 new titles in its superstores make up 20 percent of new-title sales revenue; just 500 titles make up the same portion of revenue from more than 500,000 backlist books. The book industry, says the retail consultant Paco Underhill, increasingly tends to sell books the way Baskin-Robbins sells ice cream – stocking 31 flavors to sell just 4. (His own “feelings were hurt,” he says, when he found his own book, Why We Buy, buried in the back of the Barnes & Noble superstore near his Chelsea office.)

“I disagree 180 degrees,” Riggio says. “Our stores are so big, we feature more books than anyone. There are whole sections in our stores where the stores’ managers make decisions over areas that are bigger than the whole independent stores themselves. They make it sound like we’re suppressing ideas! That is the dumbest thing in the world. We are in the business of selling ideas.”

Born on Mott Street in Little Italy, Riggio grew up at 84th Street and Sixteenth Avenue in Bensonhurst, where his mother still lives in the family’s old house when she isn’t visiting her son. “It was a neighborhood where you didn’t go looking for trouble, but if trouble came to you, you weren’t going to run away,” says Angelo “Gingie” Volpe, a sandlot-baseball teammate of Riggio’s who is now the president of Tennessee Technological University: “Lenny had a temper when he needed to.” Did anyone see the tycoon that Riggio would someday become? “As we would have said back then in Brooklyn, ‘Fuggedaboudit,’ ” Volpe says.

Riggio’s parents are a sensitive subject. His father was a high-school dropout who became a prizefighter and twice defeated Rocky Graziano – a biographical detail that floats to the top of nearly any story about his bookseller son. “It’s disgusting! That was 50 years ago,” Riggio says. His father and his boxer friends were in reality gentle, humble men, he says. “They always knew there was someone tougher.” His father drove a cab for most of Leonard’s childhood and instilled in him an iron will to succeed, Riggio says. Even as a cabdriver, his father kept training his body, believing that physical fitness was vital to mental acuity. At traffic lights, he would jump out of his cab to do push-ups and deep knee bends. “Other cabbies thought he was crazy, but they never told him to his face,” Riggio recalls.

But his father taught him other values as well, particularly skepticism toward figures of authority and a “passion for justice,” Riggio says. “My father had a strong feeling for the working person. He was a union man. And he was very much against war, even the Second World War, the so-called good war. He always thought wars were waged by people who wanted to protect their wealth and kept their kids out of it and let the common people lose their sons.”

“Our stores are so big, we feature more books than anyone. There are whole sections in our stores that are bigger than the whole independent stores themselves.”

Riggio skipped two grades before he was admitted to Brooklyn’s selective magnet school, Brooklyn Technical High School, in Fort Greene, where he studied draftsmanship, architecture, and design. “The other kids were two years older, more mature, bigger, smarter – well, I didn’t think smarter,” he says. “My friends used to copy me, if you know what I mean.” He also earned what he once called “the blackest disciplinary record” in the school.

After he’d graduated, an older friend from the neighborhood who worked as a floor manager at the New York University bookstore got Riggio a job as a clerk in its school-supplies section, and Riggio enrolled in the university’s night school to study metallurgical engineering.

For a few years, he says, he became caught up in the “tumult” of the sixties. “I began meeting hippies and people from all walks of life, this whole world that I had no knowledge of. The youth movement, the civil-rights movement, the sexual revolution – it all occurred while I was at my best.” On weekends, he would hang out at Italian social clubs back in Brooklyn, at salsa or jazz clubs in Harlem, or in discos downtown. “It was my John Travolta trip,” he says.

In his early reading, Riggio had focused primarily on Classic Comics, he says. But at the bookstore, he happened to work next to a thirtysomething Hungarian-born master’s student named George Csernovics, the paperback buyer at the time, who went on to a career in publishing at Viking Penguin. “George said, ‘Read this,’ ” Riggio recalls, “and he gave me all these serious books, by the carload” – books by authors like Hermann Hesse, Albert Camus, Thomas Mann, and Lawrence Durrell.

Riggio enjoyed hanging around Gerde’s Folk City in the Village, talking about Jean-Paul Sartre. But he never took to sitting in class. “I was determined to be a college-bookstore director and make twenty grand a year,” Riggio says, “but then I found out that I would have to wait until I was 35 or 40 before I could be hired to be the director of the NYU bookstore! I said, ‘I’m not waiting twenty years. I am already there!’ “

In 1965, when he was 24 years old, Riggio dropped out of NYU for good and opened up his own, rival bookstore – SBX, for student book exchange – on Waverly Place.

At his new store, Riggio let student radicals print antiwar materials on the Gestetner duplicating machine in the basement. “In those days, that was a weapon in the movement,” he says. “My own political persuasion at the time was very much to the left, although I didn’t particularly care for some of the contradictions in the movement, like the emphasis on personality.”

His own life began to move faster. “During the four years that I really ran the store, I had about 50 years’ experience,” he says. He married, had two daughters, and was divorced within six years. The store was drawing students from as far away as Columbia, in Morningside Heights, and St. John’s, in Queens. By 1971, he had managed to parlay its success into contracts to manage about a half-dozen other campus bookstores. That year, he borrowed $1.2 million to buy Barnes & Noble, then just a single, poorly run Fifth Avenue store with an illustrious history.

Riggio immediately adopted the Barnes & Noble name for his company, and ran it like a family. His father and two brothers all worked in the store. “His dad never acted like, ‘My son Len Riggio owns the store.’ You would never know he was Len’s dad,” said Bill Maloney, who worked there at the time. “I think Len wanted someone he knew he could trust to run the office and handle the money.” Riggio’s brother Steven, then in high school, helped part-time as a clerk, and his brother Jimi worked at the store, too. (Today Steven is vice-chairman and Jimi helps run a trucking company that ships Barnes & Noble’s books.)

Riggio soon demonstrated a knack for throwing his weight around the industry. Publishers had previously sold textbooks to college stores at a 20 percent discount off the cover price. When Riggio controlled enough college stores to give him leverage, he led a store-owners campaign to push the discounts to 25 percent. Within five years, Riggio had increased the Fifth Avenue store’s annual sales from $1 million to $10 million, he says. He bought a home on Long Island, with room for his parents and brothers. “I was on top of the world,” says Riggio. “I was my own boss. I was supporting my family. Everything else was just gravy,” Riggio says. “I didn’t open new stores to make money. It felt like a responsibility, rather than a sense of what you want to become.”

Back then, the press loved him, and the feeling was mutual. In 1974, Riggio gave one of his first interviews, to the trade publication College Store Executive. He invited its editor, Louise Altavilla, to a coffee shop across the street from the Fifth Avenue store. “Without a doubt, the concentration of management experience and bookselling know-how attests to the growth of Barnes & Noble,” her article concluded. They met again at a San Francisco book fair, and in 1981, he married her.

Riggio appeared in this magazine for the first time in 1977. He had made news by installing benches, telephones, and bathrooms in Barnes & Noble’s enormous Sale Annex on Fifth Avenue to encourage shoppers to loiter. “I grew up with one ambition: not to work for the Man,” he told New York. “And the thing is, my one accomplishment in life has been to become the Man.”

Riggio graduated to the big leagues in 1984, when he met Dr. Anton Dreesmann, chief executive of the Dutch retail giant Vendex International. The third-generation heir to a department-store fortune, Dreesmann was a bookish sort of businessman who considered himself an intellectual; he held two doctoral degrees and had written a few volumes himself. Riggio was seeking an investor to help finance his small company’s growth. He had some new ideas about running large-scale trade-book stores, like offering deep discounts on best-sellers to get shoppers in the door. The two men quickly hit it off. Riggio feverishly sketched out designs for the mammoth new stores he hoped to build, and Dreesmann loved the idea. Vendex paid $18 million for a 30 percent stake, and Riggio kept his book-loving minority partner happy by sending him free first editions, helping him develop one of the biggest libraries in Holland.

Dreesmann’s support paid off in 1986. Dayton Hudson Corp. was selling its B. Dalton chain of mall bookstores for about $275 million – about four times Barnes & Noble’s value at the time. “It was the go-go eighties,” Riggio recalls. “There were a lot of sharks swimming in shallow water.” With financing from Michael Milken’s investment bank, Drexel Burnham Lambert, Riggio managed to assemble the winning bid. Right before the deal closed, however, Drexel’s bankers had a change of heart: They would cover the $100 million initial payment only if Riggio cut them a 20 percent stake in the deal. Riggio walked out, calling the move “a bait and switch.”

The next morning, Riggio called Dreesmann, who volunteered to lend him $100 million on the strength of an oral promise, and wired the money within days. Drexel’s bankers quickly reversed themselves again and agreed to sell junk bonds to provide long-term financing for the deal. (Vendex continued to support Barnes & Noble with little profit until Barnes & Noble’s initial public offering, in 1993.)

Despite the dispute with Drexel, Riggio and Milken became friends. “I went into Barnes & Noble one day, and a big, beautiful multicolored dictionary was on sale for about $19.95 – about 30 percent of what ones like it were being sold for in other bookstores,” Milken recalls. “Riggio told me that it only cost him about $3 to print it under his own Barnes & Noble imprint, and I concluded he knew more about marketing books than anyone I ever met.”

In some ways, Riggio still runs his company like a giant mom-and-pop store. Curtis Gray, a former executive who is now a vice-president at Starbucks, recalls watching Riggio open his wallet and take out several hundred dollars to buy an aging office worker a set of false teeth. After the last San Francisco earthquake, Riggio reimbursed out of his own pocket any employee, from regional manager to store clerk, who lost property, Gray says.

But Riggio’s demeanor can quickly turn stormy. “Goddamnit, I prophesied that this would happen!” he frequently begins upbraiding the M.B.A.’s around him. “If I am going to become a prophet, then I expect to profit from it!” Former members of the company’s operating committee recall staring down at their notebooks in silence during weekly meetings to avoid getting in the line of fire.

“There are times when I fly off the handle – anybody does – but I don’t have a crazy temper,” Riggio says. “I get testy when people think they are smarter and that they can outsmart someone else. I am always exhorting our people to learn from their mistakes, as opposed to dwell on their success. I tend to be negative. I and the company are really rooted in negative self-criticism. Retailers have to be.”

Some of his displays of temper, he says, are “theatrics.” When Crown Books’ chairman, Robert Haft, ran commercials mimicking Barnes & Noble’s slogans and claiming to outdo its discounts, Riggio raged to staff, “This guy would drink our blood if we let him!” Once, after Waldenbooks’ chairman, Harry Hoffman, publicly criticized the wisdom of a B. Dalton advertising campaign, Riggio circulated a memo to his book buyers, regional managers, and store directors accusing Hoffman of “buffoonery,” “bad taste,” and “boorish behavior.” The memo explained that Riggio would not respond publicly, however, because “rolling in the gutter with a boor would only cause the casual observer to remark, ‘Look at the two boors wrestling in the gutter’ – when in reality there would be a bookseller AND a boor.”

Riggio’s zeal for self-criticism extends all the way down to his retail stores. “A store manager’s biggest fear is that you have an ugly store and he is going to visit it,” says Janine von Juergensonn, a Barnes & Noble executive and former store manager. “He sees it as reflecting his family and takes it as a personal affront,” she says.

Riggio admits he sets high standards. “Our stores are much better than other retailers’, but I hate 90 percent of them,” Riggio says. “There is only so much you can do with commercial architecture, and I am kind of a fusspot.”

During the week, Riggio lives with his wife, Louise, and their 15-year-old daughter in a Park Avenue apartment, and his chauffeur drives him to work in a Lincoln Town Car (he won’t drive up Park Avenue, he sometimes jokes, because it irks him to see the Borders on the corner of 57th Street). The family spends weekends in a palatial Bridgehampton home, originally built for a coal baron and known as “the Minden Estate,” where his mother is often on hand as well. (His father died in 1983.)

Riggio’s friends include business associates, Democratic politicos, and a handful of writers like Gay Talese. But Riggio’s companions are just as often old pals from his high school or his old neighborhood in Brooklyn. One of his best friends is a truck driver, Joe Barra, who today runs a company that ships books for Barnes & Noble.

His friend Angelo Volpe lost touch for a time and called to say that he had left a job as a professor. “Oh, do you need a job?” Riggio replied. As it happened, Volpe had stopped teaching to become a college president. “I can’t begin to count the number of people who grew up in the old neighborhood who work for Barnes & Noble,” Volpe says. “That’s Lenny.”

Riggio’s friendship can be especially helpful if you are an author. Donald Stahl, an old friend from Brooklyn Tech with whom Riggio likes to fish on Shinnecock Bay – in a small boat Stahl rents for $65 – called Riggio when his brother, Norman Stahl, wrote his first book, The Buried Man. “Lenny,” Donald Stahl said, “I never asked you for anything, and if this takes more than two minutes, forget it, but it would be nice if you could have a copy of my brother’s book put in a window of your Fifth Avenue store.” His brother received a phone call moments later. He soon happened upon his book in not just one but every window of the store. “I didn’t even want that,” Stahl says. “The word, by the way, is loyal.”

Len Riggio’s personal net worth is estimated to top $700 million, but his political beliefs haven’t evolved along with his bank account; when Fortune magazine surveyed 204 chief executives’ favorite reforms, he was the only one to call for policies to raise wages. “Money can become a burden, like something you carry on your shoulders,” he says. “My nature is to be a ball-buster, but my role is to help people.” He’s taken a hands-on role in a wide range of liberal and Democratic causes. In 1992, he threw his muscle behind Bill Clinton, but has since grown alienated over his stance on capital punishment. This year, he’s backing Bill Bradley.

Riggio is also a staunch Giuliani opponent. He stepped in for a time as David Dinkins’s finance chairman during his second mayoral campaign. After he lost, Riggio was brutally frank about his assessment, says Bill Lynch, Dinkins’s deputy mayor. “Len said it was a blow to the city for the first African-American mayor to lose re-election. He told us he thought we didn’t go to our base enough, that there were expectations there that we didn’t fulfill.”

And last year, Riggio pledged $1 million to kick off a funding campaign for his alma mater Brooklyn Tech – an effort he sees as a kind of political statement about the viability of the public schools in the face of an assault from the right. “First, it was getting tough on crime. Then we have got to kill them, so we have capital punishment. So then, okay, no parole,” he explains heatedly. “Now they go after the public schools and say they don’t work! School vouchers? I mean, come on! That’s like saying the government doesn’t work, so let’s have no government. Race becomes a handle for it, but it’s deeper than that – it is race and class.”

Riggio’s other passions – art and betting on horses – are more typical of the plutocracy, though he pursues them with surprising intensity and sophistication. He became interested in modern sculpture in 1990, when an architect Riggio hired to design a new pool house in Bridgehampton took him to the Socrates Sculpture Park, in Long Island City. Today, his Bridgehampton estate boasts one of the most valuable private collections of modern sculpture in the country, including work by Willem de Kooning, Barry Flanagan, Mark di Suvero, George Rickey, John Chamberlain, Isamu Noguchi, Claes Oldenburg, Barbara Hepworth, and Henry Moore.

Last year, he made a $1 million gift of Richard Serra’s mammoth Torqued Ellipses to the Dia Center of the Arts, its first major addition since 1983, and this January, he became the center’s chairman. Within months, he had helped forge a deal to turn an abandoned cardboard factory in Beacon, New York, into a capacious new Dia gallery space bigger than the Museum of Modern Art.

He’s also toyed with the idea of getting into the gallery business. “I wanted to open art stores, to sell art in a way that

isn’t intimidating, like I did for books. Art galleries make people feel like you don’t know anything and only they do. Even I feel intimidated. I hate museum architecture too. Frank Gehry is a great architect – I mean, brilliant – but, to me, the Guggenheim Bilbao just doesn’t work. It overwhelms the work within it.”

Don’t expect art superstores any time soon, however. “I have too much to do around here already,” he says, “especially with the whole ‘dot-com’ thing. Besides, I’m tired of commercial stuff; I’ve done enough of that already.”

Just as riggio moves to expand Barnes & Noble’s online store, Internet bookselling is beginning to draw some of the same criticisms that his superstores did. Independent stores complain that shoppers are turning up at authors’ appearances to get signatures for books that they have already bought on the Web. The New York Times played as front-page news the revelation that Amazon.com was selling promotional space on its Website. Editors warily note that marketing money may prove decisive to a book’s success online even more than in superstores. Without promotions, titles can get lost easier on a Website than in a superstore. And searching by subject always leads to the most popular book in any category – reinforcing the rich-get-richer, winner-take-all trend in book sales.

Wall Street, of course, doesn’t care about such concerns. And some analysts believe Barnes & Noble has already turned a corner. “Jeff Bezos does get a lot of free publicity, but hip and innovative only works for so long,” says Henry Blodget, of Merrill Lynch. “Riggio said, ‘Oops, I was wrong; we are behind, and I am going to attack.’ I think he saved the franchise.”

On the wall outside Riggio’s office hangs a sculpture by the multimedia artist Nam June Paik – an old Victrola’s horn painted with flowers, a small video screen at its center – that Riggio says evokes for him the theory behind both his superstores and Internet bookstores. “I had been spending a lot of time, way before the Internet, thinking about media and Marshall McLuhan’s whole concept of the global village, of building networks,” Riggio says. “When I look at Nam June Paik’s work, I think about how books, and media and television and visual art, are all about information, about programming the mind. I see connections between books and bookstores and networks.

“If a network is cool, like x-y-z discount store, there isn’t an endearing relationship between the client and the network,” Riggio says, slipping into McLuhan-speak. “But when the network gets hot, the customers bond with the store strongly, almost endearingly. That is why the great retailers’ bags become fashion accessories. At its best, a chain becomes a network, so that people who participate in Barnes & Noble activities, which include shopping, feel something in common with people in faraway places who share the same activities.”

Riggio’s superstores succeeded because they created a more comfortable – even a more communal – way to buy books, which is precisely the challenge he faces online. “The Internet affords you the opportunity to do the kind of hand selling that you logistically can’t do in a bookstore,” he says. “If a customer asks for a book and wants to see some reviews, online you can give them to him.” To that end, he has already distinguished bn.com with a host of new offerings, such as connections to The New York Times Book Review, an online catalogue of recommendations from the eggheaded New York Review of Books, the Quarterly Black Review, and a literary magazine called Tin House. And bn.com will increasingly coordinate events and promotions with Barnes & Noble stores, where you can already return books ordered online.

“How do I stack up against some other store? I don’t see that at all. How do I stack up against Mahatma Gandhi or Martin Luther King? These are the standards I aspire to.”

Not surprisingly, controversy has followed Riggio online. Last week, the ABA won a ruling from the Council of Better Business Bureaus that bn.com could no longer use its slogan, “If we don’t have your book nobody does.” Sometimes, it turns out, an independent does, so Barnes & Noble will have to modify its claim. “This is a practical and a moral victory,” proclaimed Avin Mark Domnitz, chief executive of the ABA.

“The ABA?” says Riggio. “Them again? You know, there are two ways to run a race. One way is, you try to run faster. The other way is, you try to hold on to someone else’s shorts. If you look at where I am and where I came from, that is a story about self-improvement, not vindication. How do I stack up against Amazon.com, or some other store? Egad! I don’t see that at all. How do I stack up against William O. Douglas, or Mahatma Gandhi, or Martin Luther King Jr. – these are the standards I aspire to.

“What I am trying to say is, not only am I running fast, I am running on a different track. Nobody is grabbing my shorts, and I sure as hell am not grabbing theirs.”