Recently, i was cc’d on an e-mail addressed to my father. It read, “We liked the girl’s profile. The boy is in good state job in Mississippi and cannot come to New York. The girl must relocate to Mississippi.” The message was signed by Mr. Ramesh Gupta, “the boy’s father.”

That wasn’t as bad as the time I logged on to my computer at home in Fort Greene and got a message that asked, forgoing any preamble, what the date, time, and location of my birth were. Presumably sent to determine how astrologically harmonious a match with a Hindu suitor I’d be, the e-mail was dismayingly abrupt. But I did take heart in the fact that it was addressed only to me.

I’ve been fielding such messages—or, rather, my father has—more and more these days, having crossed the unmarriageable threshold for an Indian woman, 30, two years ago. My parents, in a very earnest bid to secure my eternal happiness, have been trying to marry me off to, well, just about anyone lately. In my childhood home near Sacramento, my father is up at night on arranged-marriage Websites. And the result—strange e-mails from boys’ fathers and stranger dates with those boys themselves—has become so much a part of my dating life that I’ve lost sight of how bizarre it once seemed.

Many women, Indian or not, whose parents have had a long, healthy marriage hope we will, too, while fearing that perhaps we’ve made everything irreparably worse by expecting too much. Our prospective husbands have to be rich and socially conscious, hip but down-to-earth.

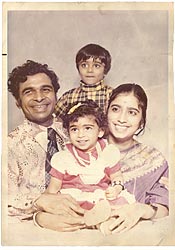

For some Indians, the conundrum is exacerbated by the fact that our parents had no choice for a partner; the only choice was how hard they’d work to be happy. My father saw my mother once before they got married. He loves to shock Americans by recounting how he lost sight of her at a bazaar the day after their wedding and lamented to himself that he would never find her again, as he’d forgotten what she looked like. So while we, as modern Indian women, eschew the idea of marrying without love, the idea that we’re being too picky tends to nag even more than it otherwise would.

Still, for years, I didn’t want to get married the way my brother did. He’d met his wife through a newspaper ad my parents had taken out. He’s very happily married, with a baby daughter, but he also never had a girlfriend before his wedding day. I was more precocious when it came to affairs of the heart, having enjoyed my first kiss with cute Matt from the football squad at 14.

Perhaps it was that same spirit of romantic adventurism that led me, shortly after college, to go on the first of these “introductions,” though I agreed to my parents’ setup mainly with an eye toward turning it into a story for friends.

At the time, I was working as a journalist in Singapore. Vikram, “in entertainment,” took me to the best restaurant in town, an Indonesian place with a view of the skyscrapers. Before long, though, I gathered that he was of a type: someone who prided himself on being modern and open-minded but who in fact had horribly crusty notions passed down from his Indian parents. I was taken aback when he told me about an Indian girl he’d liked. “I thought maybe she was the one, but then I found out she had a Muslim boyfriend in college,” he said. I lodged my protest against him and arranged marriage by getting ragingly intoxicated and blowing smoke rings in his face. Childish? Maybe, but I didn’t want to be marriageable back then. Indeed, I rarely thought of marriage at the time.

But for Indians, there’s no way to escape thinking about marriage, eventually. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that shaadi, the word for marriage in many Indian languages, is the first word a child understands after mummy and papa. To an Indian, marriage is a matter of karmic destiny. There are many happy unions in the pantheon of Hindu gods—Shiva and Parvati, Krishna and Radha.

At a recent dinner party, when I was trying to explain how single-minded Indian parents can be, my friend Jaidev jumped to the rescue. “Imagine you are on a safari in Africa with your parents,” he said. “A lion strolls by, and then perhaps a tiger. Your mother turns to you and says, ‘Son, when are you getting married? You have a girl in mind? What are your intentions?’”

The pressure on me to find a husband started very early. A few days after my 1st birthday, within months of my family’s arrival in the U.S., I fell out the window of a three-story building in Baltimore. My father recalls my mother’s greatest concern, after learning that I hadn’t been gravely injured: “What boy will marry her when he finds out?” she cried, begging my father to never mention my broken arm—from which I’ve enjoyed a full recovery—to prospective suitors out of fear my dowry would be prohibitively higher. (A middle-class family can easily spend $100,000 these days on a dowry in India.) Much savvier in the ways of his new country, my father laughed it off. “But there is no dowry in America!”

Fulfilling his parental duty, my father placed matrimonial ads for me every couple of years during my twenties in such immigrant newspapers as India Abroad. They read something like, “Match for Jain girl, Harvard-educated journalist, 25, fair, slim.” I took it as a personal victory that they didn’t include the famous Indian misnomer “homely” to mean domestically inclined.

Depending on whether my father was in a magnanimous mood, he would add “caste no bar,” which meant suitors didn’t have to belong to Jainism, an offshoot of Hinduism with the world’s most severe dietary restrictions. Root vegetables like carrots are verboten.

Still rather prejudiced against meat-eaters, my father immediately discards responses from those with a “non-veg” diet. There is, however, a special loophole for meat-eaters who earn more than $200,000. (This is only a little shocking, since my last boyfriend was a Spanish chef who got me addicted to chorizo. Once, I was horrified to discover, he’d put a skinned rabbit in my freezer.)

This desultory casting around to see what was out there has become much more urgent now that I’m in my thirties, and in their quest, my parents have discovered a dizzying array of Websites: shaadi.com, indiamatrimony.com, etc. Within these sites are sub-sites for Indian regions, like punjabimatrimony.com. You might be surprised at who you’d find on them: the guy in the next cubicle, your freshman-year roommate at NYU, maybe even the cute girl you tried to pick up at a Lower East Side bar last night.

Far from being a novel approach to matrimony, these sites are a natural extension of how things have been done in India for decades. Even since well before the explosion of the country’s famously vibrant press in the fifties, Indians were coupling up via matrimonial ads in national papers (“Match sought for Bengali Brahmin, wheatish complexion,” etc.).

My father took to the Websites like a freshly divorced 42-year-old who’s just discovered Craigslist. He uploaded my profile on several, indicating that only men living in New York City need apply (nota bene, Mr. Ramesh Gupta). Unfortunately, in the world of shaadi.com, this means most of the men live in New Jersey, while working in IT departments all around New York.

My father also wrote my profile. This may be why dates are surprised to discover I enjoy a glass of wine or two with dinner, and another couple afterward, even though the profile says “I never drink.” And he writes back to those who appear aboveboard. This is no small task, as anyone who’s done any online dating can attest. As my father puts it, wagging his head, “You get a lot of useless types.”

Like most Indians of their generation, my parents believe there are only two legitimate professions: doctor and engineer (not medicine and engineering, but doctor and engineer). Yes, they’ve heard of such newfangled professions as investment banking and law, but, oh, no, they won’t be fooled. Across India can be heard the refrain, “It is good match: They found doctor,” and my father expects nothing less for his little girl.

The problem is that while he wants doctor or engineer, my heart beats for the diametric opposite. Take the aging but rakish foreign correspondent I was smitten with last year. Nearing 50, he’d just seen his marriage fall apart, and he mourned its passing by plastering his body with fresh tattoos and picking bar fights. I found it terribly sexy that he rode a Harley, perhaps less so that his apartment was decorated with Wonder Woman paraphernalia. He was on a downward spiral, but perhaps my parents might appreciate that he’d won a Pulitzer earlier in his career?

The relationship didn’t go anywhere, as my father might have warned me if I’d told him about such things. I will admit to needing a little romantic assistance. Since moving here a few years ago, I’d hardly describe my dating life as successful. There was Sadakat, the half-Finnish, half-Pakistani barrister from London who slept most of the day and worked most of the night writing a book on criminal justice. Circumscribed within this schedule, our dates would begin at midnight. Once I fell asleep on the bar during the middle of one.

Then there were the ones who simply never called again. The boy from Minnesota who imported women’s leather clothing from Brazil, the Cockney songwriter, the French dot-com millionaire.Perhaps I didn’t want to marry these men, but I certainly wanted to see them again. I began to feel baffled by Western norms of dating, what one Indian friend calls “dating for dating’s sake.”

My father excludes “non-veg” suitors. There is, however, a loophole for meat-eaters who earn over $200,000.

Last summer, Alex, a handsome consultant I’d met at a party, invited me to his apartment for dinner. It was our first real date, and I was flattered—and encouraged—that he was already cooking for me. Soon after I arrived, we were drinking an Argentine wine I’d brought to go with his vegetarian lasagne, hewing to my restored dietary restrictions. Then, during dessert, Alex started talking about his long-distance Japanese girlfriend. I spat out my espresso. Not done yet, he also sought my advice on how to ask out the cute girl from his gym. Was it something I did? Perhaps I should have brought an old-world wine? Dating for dating’s sake indeed.

I’ve had greater luck attracting romantic attention (of a sort) on vacation. It was during a trip to Argentina that I met Juan Carlos, a black-haired, green-eyed painter—of buildings, not canvases. Within an hour of meeting me, he said he would become a vegetarian as soon as we married, that he’d never felt this way for any woman—“nunca en mi vida”—that I was the mother of his children. Oddly, by the end of the night, he couldn’t remember my name. Nothing fazed Juan Carlos, however. He quickly jotted off a poem explaining his lapse: “I wrote your name in the sand, but a wave came and washed it away. I wrote your name in a tree, but the branch fell. I have written your name in my heart, and time will guard it.”

Given such escapades, it may come as no surprise that I’ve started to look at my father’s efforts with a touch less disdain. At least the messages aren’t as mixed, right? Sometimes they’re quite clear.One of the first setups I agreed to took place a year ago. The man—I’ll call him Vivek—worked in IT in New Jersey and had lived there all his life. He took the train into the city to meet me at a Starbucks. He was wearing pants that ended two inches before his ankles. We spoke briefly about his work before he asked, “What are you looking for in a husband?” Since this question always leaves me flummoxed—especially when it’s asked by somebody in high-waters within the first few minutes of conversation—I mumbled something along the lines of, “I don’t know, a connection, I guess. What are you looking for?” Vivek responded, “Just two things. Someone who’s vegetarian and doesn’t smoke. That shouldn’t be so hard to find, don’t you think?”

It’s a common online-dating complaint that people are nothing like their profiles. I’ve found they can be nothing but them. And in their tone-deafness, some of these men resemble the parents spurring them on. One Sunday, I was woken by a call at 9 A.M. A woman with a heavy Indian accent asked for Anita. I have a raspy voice at the best of times, but after a night of “social” smoking, my register is on par with Clint Eastwood’s. So when I croaked, “This is she,” the perplexed lady responded, “She or he?” before asking, “What are your qualifications?” I said I had a B.A. “B.A. only?” she responded. “What are the boy’s qualifications?” I flung back in an androgynous voice. She smirked: “He is M.D. in Kentucky only.” Still bleary-eyed, but with enough presence of mind to use the deferential term for an elder, I grumbled, “Auntie, I will speak to the boy only.” Neither she, nor he, called back.

These days, I do have my limits. I’m left cold by e-mails with fresh-off-the-boat Indian English like “Hope email is finding you in pink of health” or “I am looking for life partner for share of joy of life and sorrowful time also.” For the most part, though, I go and meet the men my father has screened for me. And it is much the same as I imagine it must be for any active dater.

I recall the Goldman Sachs banker who said, in the middle of dinner, which we were having steps away from Wall Street, “You know, my work will always come before my family.”

Another time, I met a very sweet-seeming journalist for lunch in Chinatown. Afterward, I was planning to meet my best friend, who’s gay, in a store, and I asked the guy to come in and say hello. My date became far more animated than he’d been before and even helped my friend choose a sweater. After he left, I asked my friend what he thought. He gave me a sidelong glance, and we both burst into laughter.

As with any singles Website geared toward one community, you also get your interlopers. A 44-year-old Jewish doctor managed to make my dad’s first cut: He was a doctor. Mark said he believed Indians and Jews shared similar values, like family and education. I didn’t necessarily have a problem with his search for an Indian wife. (Isn’t it when they dislike us for our skin color that we’re supposed to get upset?) But when I met him for dinner, he seemed a decade older than he was, which made me feel like I was a decade younger.

My father’s screening method is hardly foolproof. Once, he was particularly taken with a suitor who claimed to be a brain surgeon at Johns Hopkins and friends with a famous Bollywood actress, Madhuri Dixit. I was suspicious, but I agreed to speak to the fellow. Within seconds, his shaky command of English and yokel line of questioning—“You are liking dancing? I am too much liking dancing”—told me this man was as much a brain surgeon as I was Madhuri Dixit. I refused to talk to him again, even though my father persisted in thinking I was bullheaded. “Don’t you think we would make sure his story checked out before marrying you off?” he said.

Sometimes, though, you get close, really close. A year ago, I was put in touch with a McKinsey consultant in Bombay whom I’ll call Sameer. I liked the fact that he was Indian-American but had returned to India to work. We had great conversations on the phone—among other things, he had interesting views on how people our age were becoming more sexually liberated in Indian cities—and I began envisioning myself kept in the finest silk saris. My father kept telling me he wanted it all “wrapped up” by February—it was only Christmas! Sameer had sent a picture, and while he wasn’t Shah Rukh Khan, he wasn’t bad.

Back for a break in New York, Sameer kindly came to see me in Brooklyn. We went to a French bistro, where he leaned over the table and said, “You know, your father really shouldn’t send out those photos of you. They don’t do justice to your beauty.” Sameer was generous, good-natured, engaging, seemingly besotted with me, on an expat salary—and also on the Atkins diet to lose 50 pounds. My Bombay dreams went up in smoke.

In this, I guess I am like every other woman in New York, complaining a man is too ambitious or not ambitious enough, too eager or not eager enough. But they are picky, too. These men, in their bid to fit in on Wall Street or on the golf course, would like a wife who is eminently presentable—to their boss, friends, and family. They would like a woman to be sophisticated enough to have a martini, and not a Diet Coke, at an office party, but, God forbid, not “sophisticated” enough to have three. Sometimes I worry that I’m a bit too sophisticated for most Indian men.

That’s not to say I haven’t come to appreciate what Indian men have to offer, which is a type of seriousness, a clarity of intent. I’ve never heard from an Indian man the New York beg-off phrase “I don’t think I’m ready for a relationship right now. I have a lot of things going on in my life.”

Indian men also seem to share my belief that Westerners have made the progression toward marriage unnecessarily agonizing. Neal, a 35-year-old Indian lawyer I know, thinks it’s absurd how a couple in America can date for years and still not know if they want to get married. “I think I would only need a couple of months to get to know a girl before I married her,” he says.

In more traditional arranged marriages—which are still very much alive and well in India—couples may get only one or two meetings before their wedding day. In America, and in big Indian cities, a couple may get a few months before they are expected to walk down the aisle, or around the fire, as they do seven times, in keeping with Hindu custom. By now I certainly think that would be enough time for me.

Other Indian women I know seem to be coming to the same conclusion. My friend Divya works the overnight shift at the BBC in London and stays out clubbing on her nights off. Imagine my surprise when I discovered she was on keralamatrimony.com, courtesy of her mother, who took the liberty of listing Divya’s hobbies as shopping and movies. (I was under the impression her hobbies were more along the lines of trance music and international politics.) Though she’s long favored pubgoing blokes, Divya, like me, doesn’t discount the possibility that the urologist from Trivandrum or the IT guy could just be the one—an idea patently unthinkable to us in our twenties.

It’s become second nature for women like us to straddle the two dating worlds. When I go out on a first date with an Indian man, I find myself saying things I would never utter to an American. Like, “I would expect my husband to fully share domestic chores.” Undeniably, there’s a lack of mystery to Indian-style dating, because both parties are fully aware of what the endgame should be. But with that also comes a certain relief.

With other forms of dating the options seem limitless. The long kiss in the bar with someone I’ve never met before could have been just that, an exchange that has a value and meaning of its own that can’t be quantified. Ditto for the one-night stand. (Try explaining that one to my parents.) The not-knowing-where-something-is-headed can be wildly exciting. It can also be a tad soul-crushing. Just ask any single woman in New York.

Indians of my mother’s generation—in fact, my mother herself—like to say of arranged marriage, “It’s not that there isn’t love. It’s just that it comes after the marriage.” I’m still not sure I buy it. But after a decade of Juan Carloses and short-lived affairs with married men and Craigslist flirtations and emotionally bankrupt boyfriends and, oddly, the most painful of all, the guys who just never call, it no longer seems like the most outlandish possibility.

Some of my single friends in New York say they’re still not convinced marriage is what they really want. I’m not sure I buy that, either. And no modern woman wants to close the door on any of her options—no matter how traditional—too hastily.

My friend Radhika, an unmarried 37-year-old photographer, used to hate going to her cousins’ weddings, where the aunties never asked her about the famines in Africa or the political conflict in Cambodia she’d covered. Instead it was, “Why aren’t you married? What are your intentions?” As much as she dreaded this, they’ve stopped asking, and for Radhika, that’s even worse. “It’s like they’ve written me off,” she says.

On a recent trip to India, I was made to eat dinner at the children’s table—they sent out for Domino’s pizza and Pepsis—because as an unmarried woman, I didn’t quite fit in with the adults. As much as I resented my exile, I realized that maybe I didn’t want to be eating vegetable curry and drinking rum with the grown-ups. Maybe that would have meant they’d given up on me, that they’d stopped viewing me as a not-yet-married girl but as an unmarriageable woman who’d ruined her youth by being too choosy and strong-headed.

This way, the aunties can still swing by the kids’ table as I’m sucking on a Pepsi and chucking a young cousin on the chin, and ask me, “When are you getting married? What are your intentions?” And I can say, “Auntie, do you have a boy in mind?”