In the morning of September 8, 2003, a small group of men and women gathered on a street corner in downtown Manhattan and shouted “Die, fags!” and “God is not mocked!” at the teenagers who were entering a high-rise at the corner of Astor Place and Broadway. The placard-wielding crowd, composed of members of a Topeka, Kansas, church, were protesting the opening of the Harvey Milk High School, known as the nation’s first public school for gay and lesbian youth. “I was scared,” recalls 19-year-old Chris Castro, one student who faced the protesters that day. David Mensah, executive director of the Hetrick-Martin Institute, and a driving force behind the Harvey Milk High School’s creation, was both worried and saddened. “I couldn’t believe the horrific visual and verbal assault they were subjecting these kids to,” he says.At the same time, Mensah knew that Harvey Milk faced a far graver threat than hurled abuse. Three weeks earlier, he had learned of a lawsuit seeking to have the school’s $3.2 million in taxpayer funding revoked—on grounds that Harvey Milk, which serves just 100 students, is a waste of city money and illegal under New York’s sexual-bias laws.

Almost a year and a half later, the Harvey Milk High School has failed in its bid to have the suit thrown out, and the legal challenge remains a serious danger to the school’s continued existence. That the suit was brought by a state senator known for his opposition to gay causes, and supported by an Evangelical group, has prompted some to dismiss it as reflexive homophobia. But members of the religious right are not the only ones questioning the school’s need to exist. Even some gay-rights advocates call the Harvey Milk High School a decisive step backward in homosexuals’ quest for equality and acceptance—a “uniquely bad idea,” as one liberal critic puts it. The question today is whether the city of New York has come to agree with that opinion.

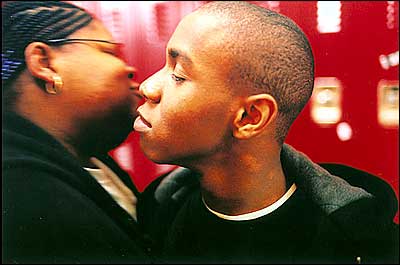

In the debate over the Harvey Milk school’s right to exist, one thing is certain: You cannot spend time within its hallways without acknowledging that it serves a real need—at least for a minuscule portion of the city’s 300,000 high-schoolers. Located on the third floor of a nineteenth-century high-rise at 2 Astor Place, the Harvey Milk High School could, with its chic multi-million-dollar renovation, be mistaken for the hip headquarters of a downtown ad agency. Eighteen spanking-new glass-walled classrooms, many outfitted with state-of-the-art computers, are arrayed along a curving hallway lined with candy-colored orange lockers. With its compact physical space and tiny enrollment, the school, David Mensah argues, is simply one example of the Bloomberg administration’s revolutionary approach to education: the breaking up of vast, anonymous, 7,000-student educational gristmills into smaller, more intimate schools devoted to a single theme—science, dance, the arts. “Within that continuum,” Mensah says, “it is simply one more very responsible option.” But by Mensah’s own admission, the school is also utterly unique: an institution based not on academic interests but on a fundamental building block of human identity—sexual orientation and gender identity. This makes Harvey Milk different from any other school in the city, or, indeed, the world—a fact hardly lost on the school’s religiously inspired opponents.

Many Harvey Milk students first come to the school as runaways seeking help from its umbrella organization, the Hetrick-Martin Institute, a social-services agency that for 25 years has been ministering to “at risk” gay teens. The school actually began back in 1985 as a tiny non-diploma-granting institution within HMI—a place for the agency’s displaced youths to earn a GED degree, taught by one full-time instructor hired by the Board of Education. Over the next fifteen years, enrollment grew from 17 to 40 students—until Harold Levy, school chancellor under Mayor Rudy Giuliani, set the wheels in motion in 2001 for the expansion of Harvey Milk into an accredited, four-year, diploma-granting high school.

At first, the newly renovated Harvey Milk High School made headlines chiefly for the crimes committed by its students. In the school’s debut semester alone, three students were arrested after a Brooklyn man was stabbed with a screwdriver at a nearby Starbucks, and four transgender students and one member of the after-school program were arrested on charges of impersonating undercover police officers and shaking down johns whom they’d lured into fake assignations—incidents that school officials blamed, partly, on the growing pains associated with a school that, within six weeks, had gone from a three-teacher GED-granting institution serving 40 students to a full-fledged public high school serving 100 students, with a new faculty of seven teachers, a principal, a new physical plant, and a new curriculum. But the tabloids had a field day portraying the school as an out-of-control collection of fashion-mad, transsexual juvenile delinquents and streetwalkers who channeled their illegal profits into buying sprees at Dolce & Gabbana. HMI’s Mensah does not deny that much of the student population does indeed belong to such at-risk groups—which is precisely why, he says, the Harvey Milk safety net is needed—but he says that the trial-by-tabloid was largely the result of discrimination. “All kids get in trouble,” he says. “They act crazy sometimes. But any time these kids got in trouble, it ended up in the paper.”

The high-profile embarrassments led to the abrupt departure of the school’s first principal, William Salzman, a former Wall Street executive. He was replaced in February 2004 by Daniel Rossi, a seasoned educator with sixteen years of experience in the classroom and three and a half years as an administrator at the Satellite Academy, an alternative high school in midtown. A short, dark, intense, gay 38-year-old, Rossi tightened admissions procedures and generally lowered what one teacher calls the “tension” that had existed under the former principal. Today, staff and students say that the school is running more smoothly, and, Rossi says, “there has been an absolute reduction in the level of violence and dysfunction” that plagued the school’s first year.

Which is not to say that the student body is no longer made up of youngsters with a lot of baggage. “A majority of our kids are what we call Title I, poverty level,” says Thomas Krever, associate executive director of programs at HMI. “About 20 percent qualify as homeless, or living with someone other than their immediate parent or guardian. They are very academically challenged. The way they see it, high-school graduation isn’t really something in their future.” But Harvey Milk’s mission is not simply to fill gaps in the students’ education; it is also to help them in the process of coming to grips with their sexuality, and the emotional trauma associated with it. “These kids are volatile, aggressive, hostile, as a way to protect themselves,” says Maria Paradiso, HMI’s director of supportive services. “They’ve been harassed and bullied and beaten up so often, they have a thick armor. We’re trying to teach them how to manage difficult emotions, how to be confident about who they are. We help them with coming-out issues, and the struggle of gender identity.”

“Imagine waking up every day,” adds Krever, “and having to be so safeguarded about the lisp in your voice or the way you hold your body, your mannerisms—every moment of your life in public—then suddenly coming into a building where that’s not as much of an issue. All those layers have to get unpeeled, all those defense mechanisms, all those levels, have to be worked out.”

The suit says Harvey Milk is a waste of city money and illegal under sexual-bias laws.

Tenaja Jordan, 19, is one student who Harvey Milk officials say is on the way to such success. A dark-skinned girl of Brazilian and West Indian descent, Jordan ran away from her Staten Island home after coming out to her Jehovah’s Witness parents when she was 16. Excommunicated by the church and rejected by her disapproving parents, she spent several weeks “bouncing around” between friends’ couches, then ended up at Hetrick-Martin. “When I got to HMI, it was like, ‘Real live gay people beside myself! Wow!’ ” Jordan says. She transferred to Harvey Milk for her final year, graduated in 2003, and is now attending college. She credits Harvey Milk with helping her to grow up—fast. “It’s more than just being gay or lesbian or queer,” Jordan says. “Most of the people I knew had also been kicked out by their parents. So we were all talking about getting housing, getting jobs, getting through school—not about the new episode of American Idol. We didn’t have time.” Jordan credits HMI and Harvey Milk staff, the majority of whom are gay themselves, with knowing how to talk to her, and how to listen. “They weren’t trying to tell me how I felt,” she says. So closely bonded do kids become that the school has had to institute an “aging out” policy: At 21, you must leave. “I’ll ease out at 21,” Jordan says. “But I’ll carry this place wherever I go.”

Principal Rossi stresses that there is no special gay slant to the teaching, and that a condition of the school’s expansion is that it operate under Department of Education mandates to teach a city-approved curriculum of math, English, science, and other core subjects. At the same time, English teacher Orville Bell admits to addressing gay issues with greater frankness in the classroom than he would in another high school. In his late fifties, Bell is an exceptionally dedicated and skilled educator with 29 years of experience in the classroom, and who is, like many of his students, both black and gay. Described by his students as one of those magical and inspiring instructors, he brings a wealth of diverse life experience to bear in his teaching, having worked in theater, run a diving and fishing business in Mexico, and done voice-over work. Bell was ready to retire from teaching, but reversed himself when he heard about the launching of Harvey Milk. “I thought it sounded wonderful,” he says. At Harvey Milk, Bell teaches works “that I would never touch in a secondary classroom,” he says, citing as an example Bent, a play about homosexuals persecuted in the Nazi death camps that includes a sex scene between two men. Bell is aware that such an admission could create controversy—especially when the public-relations person who is monitoring the interview begins to fidget and interrupt. But Bell is unapologetic about his belief in tailoring at least some of his teaching to his gay students. He’s similarly unapologetic about what he sees as the importance of having gay teachers at the school.

“Not that a straight person couldn’t do the job,” he says. “But to have openly known gay adults—whether teachers or administrators or any other position—is, I think, extraordinarily valuable, for the same reason you have women’s colleges or other types of select groups.” For Bell’s part, the greatest challenge as a teacher at Harvey Milk has been to avoid overempathizing with his students. “In the very beginning it was exhausting,” he says, “because I was crying my eyes out all the time, feeling sorry for them.”

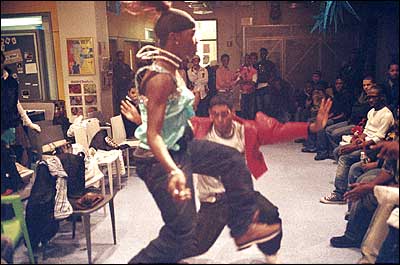

Outside of the classroom, it’s clear that gayness permeates every aspect of life at Harvey Milk, and not only because many of the girls proclaim their same-sex orientation by dressing in aggressively butch hip-hop baggy wear; or that many of the boys come to school in gender-bending wigs, dresses, high heels, and makeup. There is also the school’s tight relationship with HMI, which runs the after-school program. This includes the standard array of homework help, tutoring, and college and career counseling, but because HMI is not constrained by DOE mandates, the after-school activities are replete with gay educational subjects. Last fall, when the theater-and-pop-arts class put on a series of plays, the theme was HIV and aids prevention. In one mini-drama, a pair of male Harvey Milk students played lovers in the waiting room of a doctor’s office anxiously awaiting the results of an aids test; another skit involved a lanky male student cavorting onstage in full drag—not the kind of fare likely to be staged in a conventional after-school program. Likewise the highly popular after-school voguing class, modeled on the “drag balls” made famous by the movie Paris Is Burning.

In August 2003, Democratic state senator Ruben Diaz Sr., a Pentecostal minister from the Bronx, sued the city over the Harvey Milk High School. Diaz’s stated reason was the injustice of the city’s devoting millions of dollars to a school servicing just 100 students—“with all kind of high-technology equipment, air conditioning, the best teachers”—when so many other city schools, like those in his district, were in deep crisis. “Teachers take money from their own pockets to buy equipment,” Diaz says of his Bronx schools, “because they don’t provide the teachers with the equipment—no books, no pencils, there’s nothing for the students. You are leaving some kids behind.”

Eden Abrahams, a Harvey Milk board member, dismisses the notion that there is any unfairness in the school’s drawing money away from students in poor constituencies like Diaz’s. “The kids are from their constituency,” she says. Indeed, the vast majority of Harvey Milk’s students—some 80 percent—are blacks and Latinos from the city’s worst school districts—Harlem, the Bronx, East New York—kids whose sexuality has opened them up, Harvey Milk officials say, to excessive harassment and violence from their peers. But this does not answer Diaz’s main charge: that the $3.2 million lavished on the Harvey Milk school would, if spread more evenly among the city’s 1.1 million public-school students, benefit a great many more than the 100 students attending Harvey Milk.

Any legitimacy to Diaz’s argument, however, was quickly obscured by charges that he was acting out of homophobia. And, indeed, Diaz has a history of opposition to gay causes. In 1994, while on the Civilian Complaint Review Board, he opposed the 25th anniversary celebration of the Stonewall Rebellion, saying it would have a corrupting influence on youth and that the festivities would spread aids; and during Bush’s reelection campaign, he rallied religious leaders to support a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage. But Diaz shrugs off charges of anti-gay bias. “I’ve been getting that all my life,” he says. “There are people who love to attack you with personal name-calling, and branding you so you keep quiet. I’m not keeping quiet.” Others are—even politicians whose districts are also filled with blighted schools. “Everybody’s afraid to touch it,” Diaz says. “Who goes against the State Legislature and the city of New York? As soon as you go against what they want, they say, ‘You’re homophobic.’ And no politician wants to be branded homophobic.” As for the teachers in failing Bronx schools speaking out against Harvey Milk, Diaz says with a chuckle. “You’ve got to be kidding,” he says. “They’ll lose their job.”

Diaz found an ally—but not in New York City. In the summer of 2003, the Liberty Counsel, a Florida-based nonprofit litigation group inspired by Evangelical causes, offered to back Diaz’s suit against the city. The Liberty Counsel is also contesting some 30 same-sex-marriage cases across the country. Its leader and founder, Mathew Staver, has called Harvey Milk a “school dedicated solely to those engaged in abnormal sexual practices.” Rena Lindevaldsen, an attorney in the case, says of homosexuality, “I do believe that it’s not a right relationship” since “it’s not what God designed.” But if the Liberty Counsel’s objections to the school are based on a narrow interpretation of Scripture, the legal brief they filed on behalf of Diaz is shrewdly grounded in legal argument. The suit charges not only that Mayor Bloomberg, the Department of Education, and Schools Chancellor Joel Klein are guilty of wasting city funds at a time of severe budget distress, but it also uses a clever act of legal jujitsu to charge that the Harvey Milk school is illegal since the Department of Education’s own regulations prohibit discrimination in school admissions on the basis of sexual orientation.

The case is still before Judge Doris Ling-Cohan of the New York State Supreme Court. When she will render a decision is anyone’s guess, but Lindevaldsen says that the suit has already forced Harvey Milk to back down from its original mission. She says that the Liberty Counsel and the lawyers who represent the city have been in closed-door settlement negotiations since last summer, and that many changes have already been agreed to by the Department of Education, including the removal of language from the Harvey Milk Website that formerly identified the school as a haven for “LGBTQ” (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning) youth, as well as similar changes in the information dispensed to city guidance counselors who refer children to the school. “I would say it is a win for us,” Lindevaldsen says, adding that the sole obstacle to a final settlement is that both sides disagree on how the new rulings will be policed. The Liberty Counsel will not agree to settle until it is satisfied that the school cannot rely on a tacit understanding among the guidance counselors that only gay children should be referred to the school—which, according to her, is the nudge-nudge-wink-wink method by which the school has, so far, managed to circumvent sexual-discrimination statutes.

The city’s lawyers refuse to answer questions about the case, and will neither confirm nor deny that they have been in negotiations with the Liberty Counsel. They have limited themselves to a single written statement, which reads, in its entirety, “The high school has never discriminated on the basis of sexual orientation or any other prohibited basis.” Harvey Milk principal Rossi emphatically reinforces this point. “We certainly don’t base decisions on one’s sexuality. We can’t ask that question, by law.” While this is true, technically, it is also self-evident that the school doesn’t need to select students on the basis of sexuality since (as Rossi admits) that is done for them in the ordinary process of “self-selection.” In other words, gay kids who hang out in downtown Manhattan know that HMI and Harvey Milk are gay institutions, and it’s gay kids who apply. The numbers speak for themselves. Of the 100 students attending the school this year, there is apparently only one whom any of the students identify as straight.

Officials now insistHarvey Milkis not a gay school,but is open “to anyinterestedstudent.”

In response to the lawsuit, Harvey Milk (which initially courted the press and sought publicity for its launch) went into virtual lockdown, refusing all press interviews. It was only through repeated requests, and with the greatest trepidation, that the school finally agreed to speak to New York. In doing so, the school has clearly put itself in an awkward—if not impossible—position: promoting itself as a life-or-death alternative for the city’s gay youth, and at the same time insisting that, in fact, it’s not a gay high school at all and is open to any child who cares to apply and passes the admissions interview with teachers and staff. Principal Rossi even goes so far as to suggest that the school—despite its name, its symbiotic relationship with a gay youth agency within which it is housed, and its almost exclusively gay teaching staff and student body—got the rap as a gay high school because of the press. “Here, sexuality is not even a focus or an issue,” he claims, “but by nature of the media, it had become, I think, the perceived focus of the school.” While no one associated with Harvey Milk will admit as much, the school’s overwhelming defensiveness and bizarre triangulation—We are a gay high school, but we’re not a gay high school!—is clearly a reaction to the Diaz lawsuit.

It also, perhaps, reflects a dawning realization that, for all the school’s noble intentions, it is founded on an untenable, and indefensible, philosophical idea about the nature of public education. Indeed, one strong advocate for both gay rights and public education has emerged as a salient critic of the school. Jonathan Turley, a professor of constitutional law at George Washington University, says that Harvey Milk, by segregating homosexuals from their straight peers, promotes the return to a “separate but equal” educational system uncomfortably reminiscent of one of the most shameful episodes in American history, when black students were placed in separate schools from their white peers—supposedly for their own good. “I have a long history of supporting gay rights,” Turley says. “One can have great sympathy for the motivation behind this school but question the means used to achieve noble ends. I was flabbergasted that leaders in the gay community embraced this concept, an act of self-exile from the school system, to self-isolation. It was just unbelievable to me.”

Turley acknowledges that gay students face violence in the public-school system. But removing them and placing them in their own school is not the solution. “High schools are the most important stage of an individual’s enculturation as a citizen,” he says. “It’s in high school that they define not just themselves, but their role in society. So we should want to have interaction between gay and lesbian and straight students. This is our last opportunity to shape and monitor behavior, and we need to teach the values of pluralistic society before these people graduate, because for many of them it will be our last opportunity to exercise that level of supervision. To simply remove the object of their prejudice does not deal with the underlying prejudice.”

The bullies, he says, need to change—not by becoming gay advocates, or even by dropping their religious objections to homosexuality. “What they do need to do is conform to the requirement that those views cannot take the form of violence or harassment.” That’s never going to happen, Turley argues, when you’ve got a school like Harvey Milk that “creates this idea that gay and lesbian students are somehow different, needing special protections, some type of insular, special class that can’t stand for their own rights.”

Turley lays the blame for the school’s misguided idealism on the doorstep of the current mayor. “I think Harvey Milk High School is an enormous cop-out by the Bloomberg administration,” he says. “It would be far more expensive to deal with the underlying problem: to train teachers, to monitor classrooms, to punish prejudicial students. All of that comes with high financial and political costs; it is much easier to isolate these students and claim it as a benefit.”

Lately, there has been some evidence to suggest that the Bloomberg administration has begun to reckon with the high political cost of championing the Harvey Milk High School—not to mention the dollar cost: Since August 2003, the city has been paying lawyers, with taxpayer funds, to defend itself against the Diaz suit. When the school first opened, Mayor Bloomberg told reporters, “I think everybody feels it’s a good idea because some of the kids who are gays and lesbians have been constantly harassed and beaten in other schools. It lets them get an education without having to worry.”

But today, the mayor’s office does not return calls about the school. Another ominous sign of cooling passions within City Hall for the Harvey Milk High School are recent reports that it failed to get promised funding increases to expand from 100 to 170 students. Spokespersons for the school deny that funds were withheld, and say that the decision not to expand was made by the school itself, which feared “overcrowding”—a nonsensical claim, given that the $3.2 million renovation and expansion was expressly predicated on planning for an ultimate enrollment of 170 kids. And when the Department of Education’s Region 9 superintendent, Peter Heaney, finally got on the phone to talk about Harvey Milk, he showed every symptom of a man trying to put as much distance between himself and the school as possible. “This happened just as I was moving into the position of regional superintendent,” he says of the school’s creation, “so I can’t take credit for the decision.” Nor can he offer anything but the most lukewarm appraisal of the school academically. “I still have a lot of work to do instructionally with that school,” he says. “This is still a school where we have a ways to go.” Heaney also makes it abundantly clear that whatever mandate existed when the school was created no longer applies. “What distracts me is the misperception that it’s meant to be a gay school,” he says. “We don’t want it to be a gay school.” Principal Rossi also backs away from proclaiming the school as a bold and courageous experiment in gay rights. Reiterating that Harvey Milk is “absolutely not” a gay high school, he says, “It’s a total misperception. We’re a high school. We’re open to any New York City student who’s interested in attending. It really doesn’t matter who you are, in terms of your sexual orientation.”

It’s hard to deny the validity of Senator Diaz’s claim that the luxurious expansion and renovation of the Harvey Milk High School represents an inequitable distribution of city funds. Many more youngsters in New York will feel the lack of $3.2 million spread through the public-school system than will benefit from it at Harvey Milk. And the Liberty Counsel’s legal argument—that the school subverts the very laws against discrimination enacted to protect sexual minorities—is equally difficult to refute. Academically, the verdict is still out on Harvey Milk. Principal Rossi says that Harvey Milk, a transfer school, cannot be judged like standard public schools, which are rated according to the progress of students over the normal four-year span of a high-school education. Many Harvey Milk students transfer into the school in their senior year and stay long enough only to collect the few necessary credits to graduate. Performance is also calculated according to how many students graduate within the mandated age range for high school, which is 13 to 18. Many Harvey Milk students are two or three years behind and do not graduate until they “age out” at 21. “So all of this puts us in a unique situation,” says Rossi, “in which our client is often overaged and undercredited.” But Rossi says that “lots” of Harvey Milk students are doing better than at their previous schools, and he points out that the school’s first year’s graduating class, which had its commencement last June, had 21 students, all but one of whom met all the requirements for the diploma, and that 16 of the remaining 20 were accepted at colleges. “So in terms of academics,” Rossi says, “we’re moving in the direction we want to be.”

But it is an unspoken truth of the Harvey Milk High School that rising graduation rates and college-acceptance levels are not the only, or even the primary, justification for the school’s existence. Ask Harvey Milk’s teachers and staff why the school is needed, and they’ll introduce you to Precious Cox, a 17-year-old female who grew up in Harlem with gender dysphoria. By age 3, she refused to wear dresses, play with dolls, or socialize with girls. At Martin Luther King Jr. High School, she was teased over her masculinity. Then she transferred to Harvey Milk. Precious thrived socially and academically, earning excellent grades and becoming her class salutatorian when she graduated in June 2004. “This school is the bomb,” she says.

Not all Harvey Milk students, of course, emerge with bright testimonials. At last June’s commencement ceremonies, one female student, a friend of Precious’s, was honored not with a diploma, but with a moment of silence. Having vanished a few days before graduation, she was later discovered drowned in the Brooklyn Channel. She was 18. Precious sees the death as a cautionary example of the stresses that operate under the surface of even the most stoic-seeming teenagers. The girl had been bouncing from one temporary living arrangement to another, bathing and brushing her teeth in the school bathroom. “She was on her own at a young age,” says Precious. “She had to grow up by herself.” School officials cannot definitively say if she was the victim of suicide or some other calamity. But her death, they say, serves to underscore the very real dangers that New York City’s gay and lesbian teenagers face, and it speaks to the necessity of a safety net like Harvey Milk, even if the school cannot save every student who comes through its doors.

Jonathan Turley argues that “the great irony” of the Harvey Milk school “is that it goes against the teachings of Harvey Milk, who, throughout his career, said that the answer to any challenge based upon sexual orientation was to be open and gay, to come out of the closet, to speak up and stand up for your rights.” Turley says that it is “the total antithesis of Harvey Milk’s life to embrace a high school on the model of separate but equal.” But there is something Turley isn’t accounting for. It was precisely Milk’s clarion call to coming out that has helped to create an environment today in which children as young as 13 feel the freedom and courage to cease hiding their true natures. But in coming out, they open themselves up to hostility and violence from their peers. If the Harvey Milk School offers such children a sanctuary, however temporary, from the bigotry they face, it’s hard to believe that Milk—himself gunned down by an anti-gay colleague—would not say they should take it.