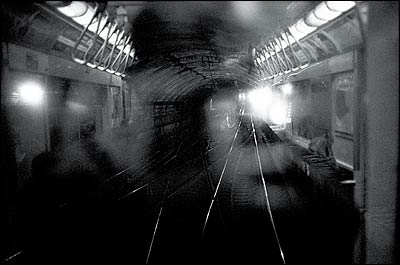

Picture this: Sometime in the near future, you get on a subway train heading into Brooklyn, and zoom into the tunnel. Unbeknownst to you, though, something bad is happening on the other side of the river. A track fire is smoldering.Throughout the subway, there is fine-grained metal dust that comes from the constant grinding of wheels on rails. It’s combustible stuff, and tonight, as the train ahead of you leaves the station, the 600-volt current from the third rail arcs and ignites some of the dust, like a Fourth of July sparkler. The sparks torch a mess of paper wedged on the tracks, left behind because budget cuts have resulted in fewer cleanups. Normally these fires are a mere nuisance—but this one really gets going, and soon the tunnel ahead of you fills with acrid smoke. The tunnel’s nearest ventilation fan hasn’t been fully repaired, so the smoke doesn’t clear. The motorman tries to contact his command center, but his radio has hit one of the system’s “dead spots,” so he gets no signal. Chaos ensues: The car fills with smoke, nobody has any clue what’s going on, and a bunch of passengers start kicking out windows in a bid to escape.

This scenario is merely hypothetical, but it’s constructed from the real, everyday concerns of transit workers, transit officials, and subway experts. From their perspective, situations like this are increasingly likely to happen, because our subway is facing a turning point: a moment when it stops improving and starts declining again.

By historic standards, the subway is at the top of its game. After $26 billion in repairs and upgrades in the past two decades, it has banished the horrifying days of the seventies, when subway wheels would fly apart in pizza-slice-shaped chunks, motors would simply drop out the bottom of cars, and the system was, by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s own description, “near collapse.” Riding the subway was almost like playing Russian roulette—derailments occurred once every eighteen days, on average.

Today, with ultrasound scans to detect faltering rails before they break, and with nearly one-third of the cars less than a year old, delays have dropped to an all-time low, and derailments happen only a few times a year. The subway even continued running during 9/11, a powerful testament to its health and the superb organization of its employees. It is the world’s most remarkable Rube Goldberg device—with cutting-edge fiber-optic switches sitting alongside pre–World War II Bakelite phones, custom-engineered radio cable running along areas festooned with dripping stalagmites, and passengers streaming obliviously by, barely glancing up from their BlackBerrys. Pull back the pavement and watch the 6,210 cars rattle along 660 miles of track, while cleanup workers dodge the trains and pick out umbrellas, wedding rings, and pacifiers from between the tracks, and it is a marvel the thing works at all, much less with such astonishing efficiency.

But the era of improvement has ended and the subway has reversed course. Money for basic maintenance has been drying up: For the past four years, the funds for keeping the subway in what is quaintly called a “state of good repair” have been 29 percent lower than the MTA’s own needs assessments, according to an analysis by the Regional Plan Association. This translated into $483 million less for the relay-and-stoplight system; $685 million less for repairing and modernizing the power substations that deliver electricity to the trains; and $668 million less for line equipment, which includes ventilation, lighting, and pumps for the tunnels. The stations themselves got $639 million less.

What makes these shortfalls so ominous is that the New York subway is always inherently falling apart—rigorous maintenance is the only defense against the natural pull of entropy. A constant infusion of money is necessary just to ward off the forces of decline, and yet the system is continually cheaped out by the state: Last month, Governor George Pataki said he would give the MTA only 69 percent of the funds it requested for its next five years of capital upgrades and repairs—an $8.5 billion kick in the trousers. The sounds of alarm are now coming not just from cranky gadflies but from the MTA chairman himself, Peter Kalikow, who recently warned that 2005 could resemble 1975, the year the subway began to decay rapidly.

Consider the system’s last, extremely weird year: Back in September, a three-inch downpour flooded the tracks and paralyzed the entire system. Just as New York City Transit was laying out plans to downsize the staff that supervise stations, a creepy string of subway shootings broke out. Then came the coup de grâce: a fire, supposedly set by a homeless man, that destroyed a Depression-era pile of relay switches at Chambers Street, and shut down the A-and-C line for nearly two weeks.

In fact, the initial damage assessment, by Lawrence Reuter, the MTA president, suggested that the line would be shut for five years, fueling the perception of a fragile system about to crumble. If an inadvertent act by a single person could knock out a vital piece of subway engineering, even the least catastrophist mind goes immediately to the question: What’s going to blow next?

If you want to understand the critical points of the subway, that charred bit of slag left by the A-and-C fire isn’t a bad place to start. It was a “relay room,” a crucial part of the subway’s nervous system, yet also one of its most ancient—a technology in use since the subway opened in 1904.

Relays are simple electromagnetic devices that let the subway know where its cars are, to help keep them from slamming into one another. Each relay is hooked up to a thousand-foot-long section of track, and a small amount of electricity is pumped into it. When a train rides onto that section of track, it shorts out the circuit, flipping the relay switch open, and letting the system know a train is there. Without that information, the system is blind, and it’s too dangerous to move cars at anything other than a crawl.

THE COMING SUBWAY CRISIS Derailed

Beset by floods and fires and built on technology that predates the Model T, the subway, the very essence of New York, has become frighteningly fragile. And now that the MTA has dug itself into a deep financial hole, it has started traveling back in time to 1975. How to Fix the MTA

A five-point plan for saving the subway. A World Class Ride

What New York City could learn from transit systems around the globe.

There are about 200 rooms crammed full of relays scattered around the system, and most observers agree they work remarkably well. Because they don’t do anything more complicated than open and close, relays can last decades before needing replacement; some of today’s models went into service before the Great Depression. “You could run the system like that for another 400 years, no problem,” one subway worker assured me.

The weakness of the relays is the wiring that leads up to them, which dates to the thirties and is wrapped in cloth so decrepit that it burns when ignited. Worse, those wires carry a searing 120-volt power supply, ten times more powerful than modern wires. When firefighters showed up to quench the Chambers Street blaze, they couldn’t use their hoses because the wiring was still live, and there was no central switch to turn it off. Transit workers had to painstakingly trace each wire back to its source and cut it manually. “Everything is hooked up to everything else. It’s an old design,” says Tracy Bowdwin, the assistant chief signals officer. The NYCT has slowly been replacing the stuff, but 41 of 200 relay rooms still use antique wiring. It won’t all be gone until 2023.

Until then, are we at serious risk of another huge, subway-halting fire? Depends on whom you believe. Reuter argues that the chances are very slim; the A-and-C fire was only the second of that nature in the subway’s entire history, with the other being a rollicking blaze that destroyed a relay room at the Bergen Street station in 1999, when water caused a short. But George McAnanama, a Transport Workers Union official, disagrees. “It’s obvious that the problems they had in the Bergen Street fire are not corrected. These fires are not an isolated event.” He says workers encounter about 100 smaller fires a month, most of which the public never hears about because the Fire Department is rarely called: “If you call the FDNY, you have to stop service. So they get subway workers to take care of the little ones.”

Another problem associated with the relays is what happens if we run out of them. Fifty-seven replacement parts had to be installed after the A-and-C fire, and according to Bowdwin, the MTA has only a few hundred backups, depending on the model, and only a tiny handful of companies worldwide still make them. If we had another big fire, observers say, we could find ourselves back-ordered on the parts—and stuck in the meantime with a subway line moving like molasses.

The subway is always inherently falling apart—rigorous maintenance is the only defense against the natural pull of entropy.

These dilemmas are partly why the NYCT plans to replace the relay system with Communications-Based Train Control. Pioneered in the Paris subway, this system tracks the location and speed of trains with radio tags and onboard lasers. Engineers get a precise computer map of where every train is, which enables them to run trains far closer together than they can under the current relay-based system. Reuter figures it’ll boost subway capacity by as much as 25 percent, which is more than the entire projected Second Avenue subway.

There are also new techniques to mitigate the problem of riders’ delaying the trains by holding doors open. Currently, on most trains, if someone jams his hand in the door, the doors open wide to let him in. New doors are controlled by software that can open them just a few inches—enough for him to get his hand out, but not enough to get inside the train. Since hand-jamming will no longer be a way to stop a train, the MTA hopes to eventually wean people off the habit entirely. “You save five seconds with every train. That doesn’t seem like much, but that’s two minutes an hour—enough time to run another whole train,” says Bob Olmsted, a former director of planning for the MTA.

Neat stuff. By the time it’s fully in place, though, you’ll be in an old-age home: The MTA’s upbeat estimates say it’ll take 30 years to finish the work. If there were plenty of cash, it might be possible to do the work faster. But on a system that needs to run 24/7, rehab work is inherently slow; workers literally have to scurry between moving trains. The NYCT picked the L line as its first experiment with the new communications system, and it has taken five years of preparation to bring it online this summer. Currently, it’s in the debugging stage, according to project manager Nabil Ghaly, and there have been some strange bugs. One engineer in Queens discovered that boys playing with remote-controlled toy cars interfered with the trains’ signals.

Assuming all goes well, the relays on the L line will be retired by the end of year, at which point the NYCT also plans to get rid of conductors on the trains, leaving only one motorman on each. This latter fact has put noses out of joint in the transit union, for obvious reasons of job loss. But McAnanama, the union rep, also warns that cutting staff onboard trains could affect public safety.

“Say there’s an incident at the front of the train, and the train operator is incapacitated. You have 1,000 people on the train, and no one to get them out. This is my disaster scenario. What do they do, walk out onto the track with the third rail?” he says. Technically, says an NYCT spokesperson, police and firefighters are supposed to handle evacuations. But workers aren’t convinced. As Kevin McCauley, a subway telephone maintainer and union rep, puts it: “Who’s going to evacuate a robot train?”

If you want to see the ghost of 1975, visit the 205th Street station on the north end of the D line in the Bronx. In a study released last August by the New York City Transit Riders Council, a state-appointed oversight group, it was declared one of the five worst-maintained stations. When I stopped by, the ceilings were a corroded mess of decaying plaster, and the walls were missing large chunks of tile. The structural pillars were chewed up, like they’d been attacked by an army of beavers. Though it was a dry day, the platform was spotted with pools of water, and the tracks were strewn with garbage, including a pair of children’s shoes tied together. “It was actually worse twelve months ago,” said a station attendant with a broom. “This looks a little better now.”

Crappy aesthetics are not necessarily a sign of imminent physical danger, but they have a tangible effect. One thing that transit administrators rediscovered in the eighties is that cosmetics matter—the better the subway looks, the more inclined people are to ride it. And the fewer riders, the less funds there are to run and maintain the system—and make it look good.

MTA officials say that no matter what problems emerge today, things are infinitely better than they were in the seventies. Indeed, they love to reminisce about the subway’s disco-era dysfunction, because it allows them to take credit for today’s remarkably clean, on-time rails. But more than a third of those improvements were financed by borrowing, and the bill is now coming due, to the tune of $1.25 billion a year in debt service, or about 15 percent of the MTA budget. And more debt is on the way: The MTA will sell another half-billion dollars in bonds this year.

With money scarce, the MTA is forced to make strategic sacrifices, and the pattern is pretty obvious. Pataki screws the MTA for cash; then the MTA turns around and screws the subway—it gave the Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North, used by a relatively affluent population, nearly 100 percent of the money they needed in recent years while delivering 61 percent to the subways. Then the subway stiffs New York’s poorest neighborhoods: Four of the five worst stations are in the Bronx.

Most subway stations don’t look half as bad as those, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t other serious problems lurking beneath the surface. Consider the never-ending fight against water. Everyone remembers last September’s flood. But few realize that on an average day—even when it’s dry outside—about 13 million gallons are pumped out of the system. It’s an unavoidable by-product of the city’s geography, and a detail of 150 transit workers does nothing but manually clean the gunk that collects in drains throughout the system.

The water problems are worse than clogged drains, though. In many areas of the city, most notably in Brooklyn, where Jamaica Water Supply Co. stopped pumping out water near the Archer Avenue extension a few years ago, the water table is rising. “It is wreaking havoc,” says Alfonce Wojicek, the NYCT’s chief officer for track infrastructure. On the Queens Boulevard line near the Van Wyck station, say subway watchdogs, a drenching downpour can submerge the tracks entirely and shut down service.

A more serious, everyday concern associated with water is that it can short out corroded parts of the electrical systems, including that age-old relay wire made famous by the A-and-C fiasco. The Bergen Street fire, too, emerged from a combination of water damage and old wires. Subway workers complain they’ve been forced to construct ad hoc devices to prevent water-related electrical fires. “The A line has still got these relay rooms that are just horrendous. They have these plastic-bag-type tarps over them to redirect the dripping water,” says Peter Foley, a former line-equipment technician who now works for the transit union. “There’s going to be another fire just because of the water dripping down.”

When fires break out, ventilation fans become critical—and currently, only about 65 percent of the subway’s fans get that “state of good repair” seal of approval. The current five-year plan calls for that percentage to rise to more than 70 by 2009, and reach 100 by 2024. “For me, the fan rooms are as bad an issue as the equipment rooms,” says Michael Sinansky, an engineer who sits on the Transit Riders Council. Every few years, there’s a serious fire on a train or track, he notes. “If those trains are in the river tunnels, and the fan wasn’t operating, it’s really a disaster.” In 1990, a fire in the Clark Street station was made worse when the fans turned on in “supply” mode instead of “exhaust” mode, blowing the smoke down onto the platform; two people died of cardiac arrest while trying to escape.

Fires can also be caused by steel dust. Six years ago, the NYCT bought two vacuum cars that ride around the system, sucking it up. That has helped. But some experts worry about the effects of the dust on the delicate lasers in the new computer-guidance systems. “You have a lot of sensitive components,” says Dennis Boyd, a train operator for 21 years. “We’ll have to wait and see.”

Finally, there is crime. Since 1997, subway crime has been cut in half, but it rose slightly last year, by 2.1 percent, including a nearly 10 percent jump in assaults. Police argue that this a statistical blip; crime is already so low that it’s almost impossible to go lower. They also point out that enforcement remains high: Transit cops made 27,303 arrests last year, a 38.7 percent increase over 2002.

But coming as it does in the midst of budget cuts, the uptick in crime is foreboding. To save money, the MTA has closed 154 token booths in the past four years, and this winter announced plans to shutter another 160—together, about 10 percent of the overall total. Removing those “eyes and ears,” say observers, is the first step toward inviting criminals back. While the MTA intends to install cameras to monitor all unstaffed areas, workers have seen enough taped-over cameras to wonder how well that’ll really work. “It’s so easy to do,” says a transit worker who asked to be anonymous. “We’ll be out in Livonia, and we’ll go fix a camera, and ten minutes get a call from the cops saying ‘Come back, there’s tape on the camera again.’”

Of course, that seems like the tamest child’s play compared with the specter of terrorism, which spooks subway riders in a way that nothing else ever has. Back in May 2002, Nicholas Casale—then the deputy director of security for the MTA—took a team of detectives on an exploratory trip. They entered three different ventilation and emergency-exit points for the subway, and climbed all the way down to the track. One of them was near “the portal,” the point where a tunnel heads out under the East River. Though the city had claimed to have instituted better security in the wake of 9/11, it was still possible for someone to plant a bomb in a place that would cause horrific damage: a tunnel that would flood with water.

“It would start flowing, and it’s not going to stop,” says Casale. “How much water is there in the East River and the Atlantic? And you can’t drop a diver down there with a cork.” Indeed, according to Casale, a recent assessment of the effects of a breach on the 63rd Street river tunnel found that it would cause thousands of immediate casualties.

Casale’s whistle-blower credibility suffered when he was later charged with fraud (on an unrelated matter) and fired from the MTA. And Reuter maintains that security has been upgraded and that, among other things, the NYCT has installed police surveillance booths at the entrance to each riverbed tunnel. Reuter won’t give further details about its preventive measures for security reasons, but he insists that “you wouldn’t be able to just walk on with a bomb and bring one of our [tunnels] down. We feel fairly comfortable that we’re as secure as we can be. We’ve protected ourselves against what could be the major catastrophic types of problems.”

Concerns about lax subway security won’t go away, though. Workers report seeing the security booths unmanned, and in January, New York Post reporter Sam Smith waltzed into several unguarded maintenance areas of the subway. A week later, he found a complete set of blueprints for the Atlantic Avenue subway station—including critical information such as the location and size of the main pillars—in a public trash can.

McAnanama, of the Transport Workers Union, contends that the blueprints were probably left by a careless contractor, which the union points to as a weak link in the security of the subway. When a private company is hired to do work in the subway, the main contractor is subject to a background check and full vetting—but nothing close to what MTA employees undergo. And if the contractor hires subcontractors, they receive even less scrutiny. “They just get their hats and clearance badges and they can walk right out onto the track. And they carry big, heavy bags around without anyone asking what’s in it, really,” says Foley, the union rep. “Get a job with a contractor. It’s the easiest way to get access to the system.” Subcontractors are often given universal keys that work on hundreds of doors.

Granted, union workers have their reasons for bad-mouthing contract workers: The contractors are, after all, taking jobs away from union members. But if security is even half as porous as critics say, all other potential subway hazards—accidental fires, radio malfunctions—seem like mere inconveniences.

For all their scary dimensions, most of the subway’s problems remain in the realm of “what-if” scenarios. Sure, lightning could strike at any time. What of it? The hazards of fires and water are real but manageable, says Reuter; other issues present graver, more immediate risks and therefore get priority, like the 1,400 switches that route trains from one track to another. If one fails, trains can collide. That pushes maintenance of the switches to the top of the to-do pile, and the fans a bit further down.

The debate over subway maintenance boils down to one simple argument that is, as it always has been, about money. As the union puts it: If basic maintenance areas have seen almost one-third less funding than needed, why not abandon new projects—such as the Communications-Based Train Control, or even the epic Second Avenue tunnel—until more of the basic stuff is in a “state of good repair”? Because, say the advocates of expansion, the subway needs to keep pace with a growing city. “We can move the number of people we move fine, but who cares? We need to grow,” says Alexis Perrotta, an associate planner at the Regional Plan Association. “The subway is an economic engine.”

At one point while exploring the system, I saw a set of stairs leading up off a platform to a door. I walked up and peered in through the window on the door—it was a relay room, just like the one that burned at Chambers Street, filled with dozens of rows of relays clicking away like a field of crickets. One subway worker told me he’d recently been inside and noticed that there were no alarms, the smoke detector had no power, and the doors were locked only with small, angled bolts you’d see on any brownstone. (The window wouldn’t be hard to break, either, he figured: “Boom, and you’re in.”) Just outside the door, I saw a little human nest: a bunch of newspapers, a dirty blanket, a bottle of Snapple, and a small jar of jam. It was the resting place for some homeless person, set up a few feet from the subway’s century-old signaling system.

Then I traveled down to West Fourth Street, where at the end of the F platform you can watch through the glass as subway workers monitor an area of track, the lights blinking as subway cars rattle by. The subway is the blood-flow of Manhattan—linking the poorest reaches of the Bronx to the tony gallery zone of Chelsea. That’s why the system’s problems can never be brushed aside: When these arteries seize up, the city is no more.

How to Fix the MTA

A five-point plan for saving the subway.

A World-Class Ride

What New York could learn from transit systems around the globe.