My first job in New York was in a new office tower on the east end of Maiden Lane. The building was clad in shiny bluish-greenish glass, a color choice that seemed an off-kilter nod to the East River churning darkly three blocks away, and the lobby was decorated with skinny trees in archetypal eighties Sun Belt–atrium style. Upstairs, in the offices, you felt hermetically sealed against the weather, the street noise, the city. These conditions were ideal for focusing on the task at hand, the moving of money from one corporation to another. But if you arrived at your cubicle very early in the morning or, more common, stayed very late at night, and glanced out the windows that wouldn’t open, you could glimpse, 38 floors below, a very different moment in the history of city commerce. If you took the elevator down and walked over, you could smell it and taste it.

Fire. Water. Stink. Fish.

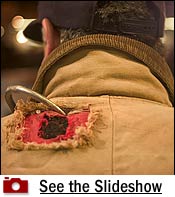

The greatest thing about the Fulton Fish Market—great if you didn’t have to work there—was its dense-pack dose of raw elements. Of evolution, really—not just the city’s, but the species’. There, squatting battered under the FDR, was a reminder of how we’d crawled out of the brackish primordial soup. You didn’t need a laminated security card to enter. Even the language of the place—mongers, gaff hooks, gurry—was gloriously vestigial. And maybe I saw a little extra in the metaphor because some of my Italian-immigrant ancestors worked there at the turn of the century.

All the hard work of blood and muscle and ice and knife will continue at the new fish market in the Bronx, in more commodious conditions and more profitably for the vendors, one hopes. For the rest of us, it’s another small loss of the old city, of the chance to turn a corner and bump into where we came from.