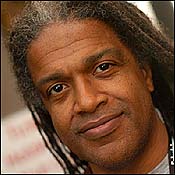

Long before Elvis Mitchell’s last movie review for the New York Times was published, on April 30, it was clear he’d been hired to play against type. Mitchell, over six feet, with two-foot-long dreads (which he tends with Kiehl’s products), robed in Costume National and Helmut Lang, will never be your average be-khaki’d Timesman. He’s bigger than life, or at least bigger than most print journalists, a road show of pop-culture exuberance who makes the rounds of TV shows, film festivals, and lecture appointments, hobnobbing with stars and industry figures.

He always seemed to be looking for something better. Which isn’t the way you’re supposed to act at the Times, which hired him in late 1999 as part of a plan to replace chief film critic Janet Maslin with a triumvirate. But he never seemed to make time for the job: A freelance editor was assigned to help focus his copy (unusual for a critic there), and there was a sense that his reviews, while entertaining, had a certain stream-of-consciousness quality to them (13 Going on 30: “Content to eat its retro snack cake and have it, too. ‘Let them eat Twinkies,’ the movie suggests”; Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights: “Like an episode of American Dreams written by Pepé Le Pew”).

Two weeks ago, Mitchell was informed by culture editor Steve Erlanger that A. O. Scott, his erudite office mate, was going to become chief critic.

As of press time, that decision hadn’t even been announced. When reached on his cell phone (Los Angeles area code 213; he never got a New York number), Mitchell refused to comment. Erlanger didn’t return calls. But Mitchell’s admirers were quick to praise him. “As a critic, he was a lightning rod for his times,” mourned Miramax’s Harvey Weinstein (who was already on the record flattering Mitchell as his favorite critic) via e-mail. “And as a journalist, he was an underappreciated asset.”

Many at the Times thought he was, if anything, a bit overappreciated. Mitchell is known for his opportunism as much as his talent, and he has a great ability to generate opportunities for himself. Often too many, to the point where it could be an editing adventure to track him down to get him to file. Nonetheless, he’s made steady progress into the big leagues from his undergraduate days at Wayne State University (where he started doing movie reviews on Detroit public radio) through a flurry of sometimes overlapping gigs at National Public Radio, the Detroit Free Press, the Village Voice, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and the Independent Film Channel.

“Mitchell is bigger than life, or at least bigger than most print journalists, a road show of pop-culture exuberance.”

“Elvis has this sort of Candide-like air about him,” says Outside executive editor Jay Stowe, who edited Mitchell at Spin (yes, he worked there, too). It’s not naïveté, exactly, but an aura of doing what he wants and seeming surprised, in all innocence, when people take offense.

A good example was in 1992, when Mitchell was recruited to a development job at Paramount Pictures by his friend Brandon Tartikoff. He was fired six months later after Paramount decided that the job conflicted with his reviewing duties on NPR’s “Weekend Edition.” (Variety reported he was “shocked.”)

He’d earned a reputation for not staying on a job too long—he never even showed up to a gig at the Los Angeles Times. (He says he was never officially hired.) When he got a job offer at a studio within the first year of his starting at the Times, many Times people, to his surprise, said to him, “We figured you weren’t going to be a lifer.”

But then again, he’d spent four years in the mid-nineties trying to write screenplays (one project was a Bob Marley movie with Ron Shelton). A bachelor, he spent months in New York Times housing before he got a place. And he seemed to enjoy the glam life a bit much for a reporter. He had a bad habit of not turning in his expenses until they’d run up gigantically, and kept popping up in the gossip columns and in the trades being considered for jobs in the industry he was covering, including being in the running at Sony Pictures (because of his friendship with its chairwoman, Amy Pascal, who is married to Bernie Weinraub, an L.A.-based Times entertainment reporter) and to be the head of Warner Independent Films. He denied both stories, but a source close to him says that he’s been up for at least two industry jobs as well as the editorship of Billboard since he arrived at the Times, and had told his bosses about it.

He also told John Darnton, the culture editor when he was hired, about being approached by Henry Louis Gates Jr. about teaching at the Department of African and African American Studies at Harvard, but his appointment to teach two classes as a visiting lecturer this semester nonetheless took the Times by surprise. (“He took another full-time job while he was working here as a film critic?” is a typical expression of culture-section disbelief.)

He quickly became larger than life in Cambridge, too—“he’s a celebrity figure around campus,” says one student—much as he is a starlike figure around Sundance, attended to by publicists.

His lecture class’s enrollment was open to whoever wanted to join. (The school even printed up a poster advertising this fact, with a picture of him grinning mischievously, his dreads hanging over his face.) It’s not an especially academic class: The students watch films (Los Olvidados; Kill Bill, Vol. 2, the day before it opened nationally; The Warriors, after which he kept repeating the tagline, “Can you dig it?”) and then write four 500-to-800-word reviews. But Harvard students being Harvard students, there’s a bit of grousing about his improvisational, meandering lecture style.

His other class, “The African-American Experience in Film: 1930–1970,” is a seminar, and a bit more intimate: He often invites his students to the Enormous Room, a campus-area bar on Massachusetts Avenue, to see one of his teaching assistants D.J. Mitchell isn’t shy; he’s extremely flirtatious, according to students who have come in contact with him.

It’s not clear if he’s coming back next year, although Gates, who needs to rebuild his Princeton-decimated department, would like him to. “I admire his toughness and rigor,” Gates says. “He was a superb presence in the classroom. I’d like to bring him back.”

Though Mitchell’s exit has more to do with the anointment of the more Timesian (and, many think, more talented) Scott, it can’t help but scratch one of the Times’ most tormenting neuroses: How unfriendly a place is the paper to blacks? And how to hold onto them? And how to avoid the perception of coddling them to the point that they live beyond the rules that other people feel they live by?

Mitchell was increasingly unhappy at the paper, those close to him say, ever since Howell Raines and Gerald Boyd were canned last summer. The Times remains an overwhelmingly white environment, however well-intentioned, and Boyd was a symbol and a presence that many black journalists found comforting. He and Boyd, the paper’s first African- American managing editor, were friends. As of press time, Mitchell hadn’t resigned officially. He’s had conversations with Bill Keller about possibly staying on to work on the Discovery Times Channel. But it won’t be as a film critic.

Which saddens Skip Gates. “He’s certainly the most powerful black film critic in history, full stop,” Gates says. “It was a great day for the race when he got that job, and it would be a shame for him to lose that platform.”