There is nothing in New York quite like the smoked-glass, gold-trimmed, pink-marbled splendor of Trump Tower. It is part shopping mall, part residential high-rise, part Trump Organization HQ, part reality-show setting, and, for our purposes, the childhood home of Donald Jr., Ivanka, and Eric Trump. When I arrive to meet Donald Jr., the lobby is filled with shoppers and tourists. And waterfalls. And the smell of food and perfume. Frank Sinatra is booming over the speakers. And a fellow dressed like a royal manservant stands guard over the elevator reserved for the Trump Organization, on the 26th floor.

The Trump offices, like the rest of the building, shriek 1983. The waiting area is decorated with mohair sectionals and potted palms and is strangely dark—like a disco in the daytime. A pretty young receptionist sits inside a leather-covered lobby-pod with Lucite stalactites hanging over her head. As I wait, enjoying the view of Central Park, I realize that I don’t even know what Donald Jr. looks like. His parents have been famous for nearly his entire life, and, at 26, he has been working for his father for three years. Yet as I’m sitting here this day a couple of months back, I can’t remember ever seeing a picture of him.

I look up as he strides purposefully down the hallway. He is tall and tan and has a thick mane of brown wavy hair that’s slicked straight back. It’s not so much that he looks like his father but that he seems like his father: big and masculine and slightly intimidating, but somehow also affable. He has the charm of the professional ballplayer who has recently signed a multi-million-dollar, multiyear contract. There are pinstripes and flashy cuff links and a perfectly knotted tie. If Don Jr. were to lose about 25 pounds, he’d be dangerous.

He flashes a toothy smile, shakes my hand, and tells me that his office is a mess, so we’ll have to talk in a conference room. He excuses himself to get us some water and returns with plastic bottles of Trump Ice. The label features a picture of his father’s face, scowling as usual, floating over a background of fire. The package design suggests that when you get to hell, Donald Trump will be there, running the joint. I look at the label again and then at Don, who rolls his eyes and shrugs his shoulders as if to say, “Don’t ask me, I just work here.”

With that one small, winning gesture, he acknowledges that he knows that I know just how strange life growing up Trump has been. It’s the reaction of anyone who’s ever been slightly embarrassed by his parents, yet loves them just the same. It’s so surprisingly normal.

And it occurs to me: Through all of Donald and Ivana’s striving and building and redecorating and self-promoting and bankrupting and divorcing and remarrying and divorcing and dating much younger people, had they somehow managed to raise at least one decent human being? In a city of vain, self-absorbed, pathologically competitive parents, Donald and Ivana seem to have won the race for the A–No. 1 biggest monsters of all. But like some kind of real-life Addams Family, are they not nearly as spooky as they appear?

The Trumps certainly would not have won any parenting awards when Don Jr. was a child. With Donald busy building his empire and Ivana helicoptering to Atlantic City six or seven days a week to run Trump Castle, there wasn’t a lot of time for helping with homework or taking weekend trips to the park. Ivana hired two Irish nannies, Dorothy and Bridget, to care for the children. But the most important early influence came from Ivana’s Czech parents, Milos and Maria Zelnicek, who lived with the family in Trump Tower for six months out of the year.

Don Jr. blamed his father. “And that’s, perhaps, not what it was. When you’re living with your mother, it’s easy to be manipulated.”

Donny, as he was then called, grew exceptionally close to Milos. As a child, he spent several weeks every summer in a town four hours west of Prague doing father-son things with his grandfather: fishing, boating, hunting. He also learned Czech, which he speaks fluently.

“My father is a very hardworking guy, and that’s his focus in life, so I got a lot of the paternal attention that a boy wants and needs from my grandfather.” He says this without a trace of bitterness.

In the winter of 1990, life as Donny knew it began to unravel. Donald was courting a pretty young girl from Georgia named Marla Maples, right under Ivana’s nose. The whole thing blew up in their faces on the slopes of Aspen. Donald moved ten flights down in Trump Tower, and war was declared. Liz Smith broke the story in the Daily News just before Valentine’s Day, when Ivana called Smith to a secret meeting at the Plaza Hotel to tell her that Donald was having an affair. “I advised her to get psychiatric help and to hire John Scanlon as a press agent,” says Smith. “Which she did, and so then he fed me all of her side of the story.”

The story stayed on the front pages of the tabloids for three months, which, as Donald likes to point out, must be some kind of a record. “The biggest story I ever covered that didn’t amount to anything,” says Smith. “It was about a fight between two people over money. And in the end, he pretty much won. Which motivated her to then innovate with all these crappy ideas she’s had that have made her a lot of money. So more power to her.” But it was also a fight over the right to raise three children, and Ivana won that battle hands down and was granted full custody. At the time of the separation, Eric was just 6, Ivanka was 8, and Donald Jr. was 12.

Between the separation and the divorce, Milos died. And shortly after that, Donald declared bankruptcy because he was $2 billion in debt. The months that followed, says Don, were especially difficult because he was, unlike his siblings, old enough to sort of understand. “Listen, it’s tough to be a 12-year-old,” he says. “You’re not quite a man, but you think you are. You think you know everything. Being driven into school every day and you see the front page and it’s divorce! THE BEST SEX I EVER HAD! And you don’t even know what that means. At that age, kids are naturally cruel. Your private life becomes very public, and I didn’t have anything to do with it: My parents did.”

Donny blamed the divorce on his father. “And that’s, perhaps, not actually what it was,” he says, a bit haltingly. “But when you’re living with your mother, it’s easy to be manipulated. You get a one-sided perspective.” He didn’t speak to his dad for a year.

At the height of the media frenzy, Ivana took the kids to Mar-a-Lago, in Palm Beach, for three months, hiring tutors so they could continue their studies. Eventually, Ivanka went off to Choate, and Eric and Donny were sent to the Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, an institution known for being regimented. “Dysfunctional families in the city all send their kids to boarding school, and that’s when they’re doing coke and getting completely messed up,” says a friend who went to school with Ivanka. “It’s like they shuffle them off.” But the Trumps, she says, did it “with love instead of being like, ‘Get lost. Go to Choate, and don’t call us.’ It was more a way of protecting them.”

For Donny, the Hill School was a huge relief. He was just old enough to have tasted what life was like without obscenely famous parents. But just as he was coming of age, the family was thrust into the public sphere. “There was a time when my parents had a lot of security guards around. Again, one of those things that I probably rebelled against,” he says. “And then, when I went to boarding school, it all kind of went away—all those inconveniences that I found obtrusive.”

A nasty divorce, workaholic parents, boarding school, piles of money—it’s often a recipe for trouble. And those same ingredients did turn some of Don’s peers into dissolute malcontents. I bring up Born Rich, the documentary about children of incalculable wealth and privilege directed by Jamie Johnson, a Johnson & Johnson heir. It’s a rather depressing film, one that leaves you with the sense that all of the subjects, which include a Newhouse, a Bloomberg, and a Vanderbilt-Whitney heir, harbor a deep resentment toward their parents. Except, that is, for Don’s sister, Ivanka. She comes across as uniquely well-adjusted, articulate, poised, respectful, and of-this-planet.

Don launches into a good-natured semi-rant about the rest of the film’s subjects, most of whom he knows. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says, his voice rising an octave. “I was like, ‘Do you hear the words that are coming out of your mouth? Are you out of your mind?’ Their parents gave them anything they could have ever wanted. And they hate their parents! I’m not close with any of them, but it’s very one-degree-of-separation.”

How did the Trumps escape this fate? The most important thing his parents did, says Don, was to make the kids work as teenagers. Donny’s first job, at the age of 13, was as a dock attendant at the marina at Trump Castle, making minimum wage plus tips tying up boats. “We were spoiled in many ways, but we were always taught to understand the value of the dollar. If there was something we wanted, we had to earn it. Even in college, we were very fiscally responsible. I had 300 bucks a month; anything I wanted beyond that, I had to work for.”

Not that Don never had his problems. It was during college, at the University of Pennsylvania, where he was enrolled in the Wharton undergrad program, when the repressed anger surfaced and the rebellion began. He had a reputation for getting into drunken, do-you-have-any-idea-who-I-am? fights. “To be fairly candid,” he says, “I used to drink a lot and party pretty hard, and it wasn’t something that I was particularly good at.” He laughs. “I mean, I was good at it, but I couldn’t do it in moderation. About two years ago, I quit drinking entirely. I have too much of an opportunity to make something of myself, be successful in my own right. Why blow it?”

When Don graduated, he decided to take a year off and live in notoriously boozy Aspen, Colorado—something his parents did not like one bit. (They know as well as anybody that Aspen spells trouble.) “I had a great time,” he says, “but your brain starts to atrophy. It just wasn’t enough for me.”

No one in his family believed Don would ever come around to work with his father. “But I knew that it was something I wanted. I was following my dad around from a young age. I don’t know if it’s genetic, or just because I was surrounded by it, but I was always fascinated with building and construction and development. I guess I just wanted to make sure that I was making the right decision.”

Just then, an older gentleman peeks his head into the conference room to tell Don that he has a meeting scheduled and needs us to move. For a second, I think he’s going to pull Trump family rank, but then, very politely, he asks, “Is someone in the large conference room?”

Indeed, there are people in that room. “Okay,” says Don with a bit of macho swagger, “we’ll slide over there and kick them out.” In the end, he does not make anyone move but asks to borrow someone’s office. When we settle down again, I notice that there’s a Donald Trump doll sitting on a shelf above our heads.

One of the most appealing things about Donald Trump Jr. is that he does not seem the least bit tormented about the fact that his father is Donald Trump Sr., though he does concede that the universal reaction he gets at airline check-in counters or whenever he uses his credit card—>I?“Donald Trump?! You don’t look like Donald Trump!”—has grown tedious.

“I think I probably got a lot of my father’s natural security, or ego, or whatever,” he says. “I can be my own person and not have to live under his shadow. I definitely look up to him in many ways—I’d like to be more like him when it comes to business—but I think I’m such a different person, it’s hard to even compare us. His work persona is kind of what he is. I have a work face, and then there’s my private life.”

Today, his work for the company is mostly in acquisitions and development, focusing on the redevelopment of the old Delmonico Hotel at 502 Park Avenue and the Chicago project seen on The Apprentice. He works closely with his father, talking to him about business at least once a day. “He’s a very fair boss,” says Don. “At the same time, you have to be on top of everything, because there’s no one who works harder than he does. He’s a machine.” He laughs. “I’ll check myself, in the sense that I’m not going to do anything in a disrespectful manner in front of other people, but there’s a point where I’ll go into his office and close the door and it’s like, ‘Listen, this is crazy.’ But he can ride me harder than he can ride the other people because … he’s my dad.”

The transformation from angry Donny to self-possessed Don has surprised a lot of people. “I used to really think that Donny would one day just get on a boat and sail away and leave this world. Those periods when there was the drinking were his way of escaping,” says one person who knows the family. “I was pretty shocked when I realized how deep some of his problems have gone. I’m so happy he turned a corner.”

It helped that he was able to screw up without the world watching. Thanks to his parents, he’s kept a remarkably low profile over the years. “When I was younger,” he says, “I went out of my way to avoid any kind of media attention. To this day, I meet people and they’re like, ‘I didn’t know he had a son! You mean Ivanka’s not the only one?’ She did her modeling thing, she was out there a little bit more. But if there was a reporter within 100 miles, I was in the background somewhere, trying not to be seen.”

But there is, I suspect, another reason Don stopped fighting his birthright and learned to love being a Trump: Despite his protests to the contrary, he is his father’s son. One woman who went to the University of Pennsylvania with Don tells me, “He was almost disappointingly normal.” To the chagrin of the fraternities for rich, well-connected kids—and despite their clamoring for his membership—Don chose FIJI, a frat known for attracting “regular guys.” His girlfriend, on the other hand, was widely considered to be the hottest girl in his class. This, of course, sounds an awful lot like his boss, a man who cares very little about running with the in-crowd but who plainly enjoys the company of a foxy lady.

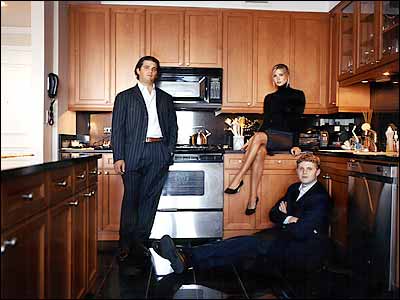

A couple of weeks later, Don Jr. and I are sitting in his apartment with Ivanka and Eric. All three kids have their own place in a different Trump property. Eric lives in Don’s old rental in Trump Parc on Central Park South. And Don and Ivanka recently bought apartments (they pay their own mortgages) with money that was given to them over the years by Donald’s parents, Fred and Mary, and then wisely invested. Ivanka paid $1.5 million for a two-bedroom at 502 Park Avenue, and Don paid $990,000 for a nice but unassuming two-bedroom at Trump Place, the soon-to-be-sprawling city within a city that will eventually include sixteen high-rises along the Hudson River. One day, not only will it all be theirs, but they will probably have been responsible for building much of it. Ivanka, a Wharton B-school grad, plans to join the Trump Organization after she finishes her stint working for Bruce Ratner, the Brooklyn developer, as does Eric when he graduates from Georgetown next year.

Don has to get to the office, but Ivanka and Eric stay behind. In person, 23-year-old Ivanka is startlingly beautiful. Her poker-straight hair is pulled back into a tight ponytail, and she’s wearing a black pencil skirt and a clingy turtleneck. She speaks with almost too-perfect diction—in a Madonna-like “European” accent. Eric, who is the tallest at six five and youngest at 20, is gangly and a bit shy. Though he lacks the confidence of his brother and the glamour of his sister, he is, like them, unfailingly polite and well-spoken.

The kids agree that there’s a lot of sibling rivalry. “We were sort of bred to be competitive,” says Ivanka. “Dad encourages it. I remember skiing with him and we were racing. I was ahead, and he reached his ski pole out and pulled me back.”

Eric laughs. “He would try to push me over, just so he could beat his 10-year-old son down the mountain.”

Like Don, they seem to have an almost cultlike reverence for the family business, despite the risk of living in their father’s shadow. “We’ve all made peace with the fact that we will never be able to achieve any level of autonomy,” says Ivanka. “No matter how different a career path we choose from our parents, people will always say we wouldn’t have gotten there if it hadn’t been for our name. And in the end, there’s no way to tell if that’s true or not. Maybe it’s not the worst thing for people not to see you coming. If people want to underestimate me, I’m fine with that.”

I ask Ivanka to take a stab at why she and her siblings seem to have avoided the pitfalls inherent in being raised by rich, famous parents. After spinning out a few bromides about how youth and wealth don’t mix, she cuts herself off and levels with me: “Look, none of us are saints. We all like to have fun. But I think our parents have just been pretty tough with us. They’ve always made sure that we lived within some realm of reality.” Despite their personal extravagance, Donald and Ivana managed to filter out the excesses of modern life for their kids. “I don’t know how they figured it out,” says Ivanka, “but they knew the perfect way to give us what we needed without it being gratuitous.”

Inevitably, the conversation turns to The Divorce. “I realized what was going on the least because I was the youngest,” says Eric. “But I do remember friends bringing me newspaper articles—which was worse.”

“One day,” says Ivanka, “I walked out of school and there was a horde of photographers waiting for me. I remember going to get into the car and there were just masses of people coming up and asking my response to comments that people had made and that I did not understand. It was horrible.” She sighs. “In retrospect, I can look back and say, ‘How was it possible that we didn’t have to go to intense therapy for the next eight years?’ ”

Eric, who seems the most inclined to look on the bright side, believes his parents’ breakup cemented a deeper bond between him and his siblings. “Donny, in a way, is like a mentor. He kept tabs on everything that my grandfather taught him over the years and that I was too young to appreciate. And I’m definitely closer to Ivanka because of it. She took me under her wing and raised me, took me shopping, tried to make me cool.”

“I think this,” says Donald.“I’m a really good father,but not a really good husband … I didn’t leave for another woman, by the way. I didn’t leave for Marla. I left.”

Ivanka looks at Eric and says, “Bizarrely, it also made us closer to Dad. Don’t you think? Every morning before school, we’d go downstairs and give him a hug and a kiss. We didn’t take his presence for granted anymore.”

They admit that the hardest part was when both parents started dating. “I had a lot of resentment,” says Eric, “especially for those people.”

I ask about Marla and her daughter, Tiffany, who recently turned 11. Ivanka talks about seeing her half-sister last Easter, but does not mention Marla. Eric says nothing.

They are slightly more comfortable discussing Melania, Donald’s fiancée, who is twelve years older than Ivanka. “She’s really nice,” says Ivanka cautiously. “She’s a good person, and we appreciate that. I think we’re all getting to know her a little bit more now.”

Eric pipes up: “We’ve actually seen our father being happy, you know, really enjoying this person and her doing a lot for him, and therefore we appreciate her as opposed to resent her.”

Earlier, I had asked Don if there was anything he would change about either of his parents if he could, and he laughed, aware that he was heading into treacherous territory. He thought for a minute and then said, “My father could be more understanding of things he doesn’t … understand. You know? If I want to go fishing rather than play golf, it’s always like, ‘Why would you go fishing all weekend? I don’t get it! It’s crazy!’ ”

When I mention this to Eric and Ivanka, there’s an instant look of recognition. “I went to Hawaii,” says Eric, “and he was like, ‘Oh, don’t go to Hawaii!’ He had disdain.”

“I just came back from Hawaii two weeks ago,” says Ivanka, “and that was exactly his reaction.” They both laugh. Eric, who is now standing and looking out the window, does a bellowing imitation. “‘Why don’t you just go to Palm Beach? We have Mar-a-Lago!’ ”

Is there an equivalent trait in your mother, I ask, something that the three of you laugh about?

“Oh, we laugh at her a lot,” says Ivanka. “Mom’s funny because she’s really, like, exuberant. I’ve never met anyone who has a more effervescent character.”

When the gates—and they really are gates—to Ivana Trump’s limestone mansion on East 64th Street swing open, I’m greeted by Dorothy, the onetime nanny who is now Ivana’s personal assistant. She deposits me on a red velvet settee and goes upstairs to announce my arrival. The house, with its red carpeting and gold fixtures and chandeliers and Impressionist-style paintings, is so very much, and yet it is still, somehow, traditional, barely hewing to a tricked-out Louis the Someteenth sensibility.

Seeing her on television or in magazines cannot prepare you for the jolt of intensity and costume drama that is Ivana. Her hair is up, in that modernized beehive we are accustomed to, and she is, for daytime, a touch over-bejeweled. Her pin-striped mini coat-dress is as short as it can get without being wildly inappropriate. On her feet are a pair of red patent-leather stilettos, the heels of which are shiny metal spikes.

Even at 55, she is still somehow girlish and sexy. She has, for example, a most unusual giggle, which punctuates many of her utterances. She also still speaks in that slightly broken, heavily accented English, which often leads her to unintentionally hilarious syntax (“The Donald” being the most famous). She tells me that she lives half of the year in New York and Florida, and the other half in Europe. She owns this house, one in Palm Beach, a condo in Miami, a house in London, three in the Czech Republic, another in Saint-Tropez, and “then I have my yacht, which is floating somewhere in between.” Giggle, giggle.

Ivana seems to have prepared for this interview about her children. Before I can get off a single question, she launches into a parenting lecture: “To raise the kid in today’s society, with all the temptations they have around, it really wasn’t for me that hard. Because I was born in Czechoslovakia and everything was quite spartan. From the age of 6, when I won my first race in skiing, I was on the national ski teams, really until Olympics in ’72, so I always had a lot of discipline and commitment to achieve as much as I could in good way. Competitiveness doesn’t stop when you stop skiing. There were great values instilled in me and is exactly what I did with the kids.”

This reminds me of something Liz Smith had said when I called her for some insight into what I began thinking of as the Trump parenting miracle. “Even I’m sort of amazed that it seems to have come together for these children,” she said. “All I can figure is, Ivana is really a nice middle-class woman at heart, despite her foolish personal style, her off-the-wall behavior, and her picking up these Italian lovers just to prove that she’s not rejected. And the thing that always guided Donald was the influence of his father and mother, Fred and Mary, who were two really solid people. Here’s the thing: Neither Trump drank or took drugs, and they didn’t really play around a lot. Of course, Donald did a little bit. He broke up his marriages, always over some irresistible woman. But he wasn’t just running around and hitting on girls. In spite of making their children live in this artificial palace on the top of Trump Tower with all this gilded rococo crap and jets and private boats, the children, I think, were just pretty normal. And I think they had real love and guidance from Ivana. And even from Donald. I don’t want you to laugh, but they had a lot of family values.”

Chief among them was the value of hard work. “That was really important,” says Ivana of the decision to make the children work when they were teenagers, “because I see so many kids which are my friends’ children—really good friends—and they’re so messed up. They drink, they’re on the drugs, they don’t want to work, they have no ambition. They get all the money in the world. Why they should get up before eleven o’clock? They’re real losers.”

Ivana takes a lot of pride in how well things turned out. “I say, ‘Look at my kids! How fabulous are they?’ I did everything I was supposed to do: got them off to university, set them for life. And now it is Donald’s turn.” Donald didn’t know what to do with the kids when they were little, she says. “He’s not the kind of father who would ‘Choo-choo, goo-goo, noo-noo.’ He would love them, he would kiss them and hold them, but then he would give it to me because he had no idea what to do.” But now that they’re grown, she says, “he’s starting to learn them, teach them, and now it’s going to be his thing.”

Ivana eventually winds her way around to The Divorce. “When we did the separation, one thing I made sure of, I never, ever show any panic. I never cry in front of them, I never scream in front of them. Because if they would see that I’m in a panic, they panic, too. Sometimes I just wanted to”—she twists her jeweled hands into tiny, angry fists—“kill or scream. But I did not do it. That was No. 1. No. 2: I never, ever spoke one bad word against Donald. It’s the only father they have and they will have. So they were my two rules.”

It is obvious that there is some part of Ivana that has never quite gotten over Donald. “When you are married to somebody,” she says, “there is always chemistry.” When I tell her that all three of her children joked about their father’s inability to comprehend, for example, wanting to do something so crazy as go to Hawaii, she, too, rolls her eyes. “I can hear him! ‘Why don’t you play golf? Come on! Fishing? What do you do with the damn fish?’ ” She seems to drift off into a tiny moment of nostalgia for the old routine. Oh, that Donald!

Was Donald a good husband? I ask.

“The record speaks for itself,” she says. “He eventually got what he wanted: a new wife. And that didn’t work out, so … ”

Have you ever talked to Marla Maples?

“Never.” Pause. “Never. I’ve got nothing to talk about with her. She actually apologized to me in the Daily Telegraph in London … What’s done is done. I have no animosity against her because look what happened.”

For the past two and a half years, Ivana has been dating a man 22 years younger than she is, an Italian gentleman from Rome named Rossano Rubicondi. Just before our talk comes to an end, he appears, and I think for a second that he is one of the men there to fix a leak. He is tan, with dark curly hair, and he’s wearing Diesel jeans, a faded T-shirt, and leather boots. “I feel great,” she says, when I ask about their relationship. “I go to the new places with Rossano. He’s a young man. He’s 33. And he’s fantastic.”

In a recent interview in which she talked about dating younger men, Ivana said, “I’d rather be a babysitter than a nurse.” From that quote came the idea for her reality show. She pauses for effect. “It is called Ivana Young Man.” Peals of giggles. The premise of the show, which will air as a two-hour special on Fox early next year, is simple: Twentysomething guys compete for the hand of a 40-year-old woman who has everything but a man. Ivana will host. “If she makes a wrong decision eliminating a guy,” says Ivana, “I can overrule her.”

Ivana bristles at the suggestion that she is in competition with Donald. She wrote books before he did, she argues, and she was offered reality shows before The Apprentice was even an idea. But then she mentions that she is also building a “$150 million condominium project,” the Ivana Great Barrier Reef, in Australia, and that she is the spokesperson for another condominium complex, Bentley Bay, in Miami. “So I’m still in construction. And I have a huge project that I really can’t speak about yet, but it’s going to be a huge billion-dollar tower which I’m working on.”

Can you say where?

“Cannot say. Cannot say. Because … The Donald is going to freak out!” Gleeful, maniacal giggles.

To sit in a chair opposite The Donald is to feel as if you’re taking a meeting with the king of Manhattan. He sits behind a huge desk piled with work, and has a commanding view of … everything, really. The room is a monument to his ego and success: There’s an Apprentice poster, blowups of his book covers, miniatures of some of his buildings, and framed magazine covers spanning more than twenty years. I try to keep in mind what Don Jr. told me about his father: “Other than his balance sheet, there’s not many ways in which he’s that different from the average American guy. He wants to eat his hamburger with his ketchup and his Coke, and that’s it.”

When I sit down, Donald Sr. asks me several questions, often cutting me off in mid-answer to ask another. He gets bored easily, even with himself, often interrupting his own conversation by changing the subject without warning. Sometimes he asks and answers his own questions, or ignores something I’ve said and talks right on through to whatever topic has popped into his head. This sounds like it would be infuriating, but it is, instead, a fascinating display of unfettered id.

When he’s had enough of our small talk, he claps his hands together and says, “Tell me about my children.” Before I get far, he jumps in, “Let me tell you one thing: Ivanka is a great, great beauty. Every guy in the country wants to go out with my daughter. But she’s got a boyfriend,” 24-year-old socialite Bingo Gubelmann. He goes on for a bit about how proud he is of Ivanka’s various accomplishments. (When I asked Don if there was any favorite-playing, he said, “Come on! Daddy’s little girl!”) Suddenly, Donald Sr. remembers something: “You know I have another daughter, with Marla, named Tiffany? She’s just a beautiful great kid also. But it’s very separate. When you have separate wives, it’s sort of … separate. Marla was a good person, as was Ivana. But I’m married to my business. It’s been a marriage of love. So, for a woman, frankly, it’s not that easy in terms of relationships. But there are a lot of assets.”

When I call Marla, who lives with Tiffany just north of Los Angeles, she agrees with Donald’s assessment of his true love. “There were times when all of us wished we had more of Donald’s ear and his focus, especially when we’d have family dinners on Friday.” She laughs. “ ‘Can you turn off the financial news for a moment, please?’ But those kids always knew that he was unique in a way, that he’s got to run that company. I’ve watched that also with Tiffany. A lot of the fathers are here for all her basketball games, but she knows her dad loves her.”

As far as being the other woman partly responsible for such a spectacular end to a famous marriage, she says, “It was a time of just an absolute broken heart every day. I just wanted to reach out and embrace the kids, but unfortunately, because there was no dialogue with Ivana, it made it very difficult. Goodness gracious, we all wished it could have been different. But then you see how everyone comes out in such a beautiful way.”

Back in Donald’s office, he says, “I’ll tell you what I’ve learned: Children are tough. Much tougher than people think.” Still, it’s easy to feel the crosscurrents of guilt and defensiveness. “I think this,” he continues. “I’m a really good father, but not a really good husband. You’ve probably figured out my children really like me—love me—a lot. It’s hard when somebody walks into the living room of Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach and this is supposed to be, like, a normal life. But they’re very grounded and very solid. The hardest thing for me about raising kids has been finding the time. I know friends who leave their business so they can spend more time with their children, and I say, ‘Gimme a break!’ My children could not love me more if I spent fifteen times more time with them.”

He’d like to be optimistic about the prospect of having the three siblings take over the business one day. “Well, their mother wants them to come work for me,” he says. “I would like that, actually. It would be a great help for me. There’s something really nice about family when it works. But there’s something terrible about family when it doesn’t work in business. And I’ve seen both. Richard LeFrak is a good friend of mine. He’s got two sons, and it just works very nicely. But for every good example, I can give you twenty horrible examples.”

Despite the fact that Donald and Ivana are coordinating a parenting handoff of sorts, they don’t often speak. “I can understand there’s a lot of animosity,” says Donald. “I didn’t leave for another woman, by the way. I didn’t leave her for Marla. I didn’t leave for anybody. I just wanted to leave. I left. Do we get along?” Here, his voice goes up an octave, “Yeeeaah, we get along, but it’s not exactly the greatest friendship. With Marla, I have a very good relationship. It’s always better to have the good relationship because of the children.”

It comes as a relief to realize that Donald Trump does have a modicum of understanding that his choices in life affect his children. Still, when I tell him what Ivanka said about the divorce bringing her and her brothers closer to him, he is caught off guard. “Brought them closer to me?” he asks. Yes, I say. “Oh,” he says. Donald Trump pauses to reflect for the first time in our conversation. “That’s interesting.” He gets a faraway look in his eye, and for a second I think he’s going to say something sentimental—touching, even. Fat chance. “I think they also got closer to me because I’m very business-oriented,” he concludes, “and as they got older, they got more interested in the business.”

Though the success of The Apprentice has made their father busier than ever, the Trump kids agree that the show has been good for the whole family. For one thing, their dad needs them around to help mind the store. But more than that, the show has humanized their father—or “Mr. T,” as he’s known around the office. The appeal of The Apprentice—indeed, the show’s very premise—is Donald Trump as a kind of national father figure. Perhaps it’s the way he seems to care for the contestants, even as he is firing them. Judging by the show’s success, people love his brand of tough love.

In reality—not “reality”—it is Donald Jr., Ivanka, and Eric who are the Apprentices, and Don Jr. is the furthest along in his training. “The Apprentice has been excellent for my dad,” he says. “Before, there was always that kind of corporate, Napoleonic evilness to Donald Trump. Now people see him interacting with normal—barely normal—individuals, and it’s like, ‘Wait a second. He’s a regular guy!’ People realize that he’s not this Ken Lay, Mike Milken type who spends his days screwing people over. So, it’s been great for him.” Then he adds, “Beyond all of that, it has been great for the brand, and ultimately, that is something that’s very important to all of us.”

With this last comment, it’s clear that Donald Jr. is truly his father’s son. A few weeks ago, I woke up and was shocked to find the younger Trump’s mug in the place where both his parents have reigned for so long: the tabloids. He was taking a beating for being “tacky,” a “cheapskate,” and “taste-deprived” after he proposed to his girlfriend, Vanessa Haydon, described as a “sometime model and aspiring actress” (which, of course, sounds an awful lot like the type of girl for whom his father has gone weak in the knees). It wasn’t the proposal that raised eyebrows; it was the fact that he popped the question in the presence of reporters and photographers at Bailey Banks & Biddle in the Short Hills Mall in New Jersey. Classy, no? The assumption was that he got the $100,000, four-carat ring on trade for turning what many would consider to be the most private of moments into a publicity stunt. The Donald couldn’t have orchestrated it better himself.

In the end, it seems, none of us can avoid turning into our parents. But if Don Jr. is becoming just like his father, perhaps that’s not such a bad thing. Let’s face it: The Trumps may not be monsters after all. Indeed, there is something surprisingly lovable about them. Perhaps the children have not just survived their strange parents, but thrived because of them.

For more photos of Donald Trump and his children, see the December 13, 2004 issue of New York Magazine.