By the spring of 1972, Susan Sontag had spent nearly two years away from New York. She had directed her second film, Brother Carl, in Stockholm, and put it in the can. Two months in Paris followed. There, Simone de Beauvoir handed the 39-year-old essayist-auteur the rights to adapt her novel She Came to Stay to the screen. As Sontag later told a Berlin conference, she considered Europe to be “liberation”—most specifically, the sojourn, with its focus on filmmaking, represented freedom from the writing of essays, a torturous multi-draft up-all-week slog. Europe had also liberated her from her increasingly smothering American celebrity.

As she prepared for her return to New York to resume writing, Sontag confided to her publisher, Roger Straus, that she felt more than a little hesitant about her homecoming. Straus was the perfect confidant to hear her qualms about celebrity; he continually confronted them. Since the 1963 appearance of her first novel, The Benefactor, Straus had served as Sontag’s greatest patron and savviest publicist. Sontag’s return to New York prompted fresh bouts of anxiety over her role as an arbiter of cultural and intellectual debate. Only now, Sontag seemed resigned, thanks to a sheath of ironic self-insulation, to her “pop celebrity fame.” She wrote Straus, “I’m back in the race to become The Most Important Writer of My Generation and all that shit.”

Her sardonic crack betrayed an emotion that Sontag had a hard time shaking in her remaining three decades: ambivalence. As a thinker, she frequently found herself driving in reverse. After urging critics to unbutton and enjoy the pleasures of popular culture, she spent her last decades straining to reclaim serious-minded moral authority. She lamented the desensitizing flood of photography in one book, then recanted her warnings and celebrated the medium’s empathetic power in another. Early condemnations of the “arch-imperium,” America, were followed by impassioned support of Bill Clinton’s interventions in the Balkans and further followed by a New Yorker essay attributing 9/11 to wrongheaded American policies. But of all the circles she tried to square, none proved more nettlesome than the reconciling of her responsibilities as an intellectual and the realities of her rock-stardom, the awkward coupling of the “Important Writer” and “all that shit.”

In conversations with friends, that anxiety frequently surfaced. The poet Richard Howard told me that she considered the notion that she was an intellectual “rather to her horror.” He added, “She didn’t want to be called an intellectual. She answered the call when it came. When addressed that way, she would respond. But she didn’t like it.” Instead, Sontag preferred to think of herself as a novelist—an eccentric choice, given that critics held her essays in far higher regard than her fiction.

Indeed, Sontag had even more compelling reasons for distancing herself from the New York–intellectual label. When she first fully emerged on the scene, with the coolly composed 1966 broadside Against Interpretation, “New York intellectual” came loaded with meaning. It described a self-identified coterie of a particular time and place, arguing in little magazines like Partisan Review and Commentary, with a very specific critical and political mission, marching under the dual banners of modernism and Marxism. Sontag—with her championing of European modernism, her unabashed intellectuality, and her left-wing ideological commitments—could plausibly be placed on this row of the periodic table of American intelligentsia, alongside Alfred Kazin, Dwight Macdonald, and Lionel Trilling. She may even, in a way, be the last significant member of this crowd.

But this was also where her ambivalence appropriately kicked in. In her critical writings, and in her public persona, she reflected—and directly contributed to—the demise of the older breed of New York intellectual. Her celebrations of pop culture erased the old boundaries that limited the acceptable subjects for serious criticism. Against Interpretation made a powerful case against the Partisan Review style of literary criticism, which focused on the moral and social content of art. “Like the fumes of the automobile and of heavy industry which befoul the urban atmosphere, the effusion of interpretations of art today poisons our sensibilities,” she wrote in the book’s introductory essay. “Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art.”

There was an even more profound, albeit less intentional, way in which she shattered old taboos and remade the world of the New York intellectuals. As her writing gleefully stomped on the old distinctions between high- and lowbrow, so did her persona. She became a fixture of the popular culture—a magazine cover girl, grist for Saturday Night Live, a reference in Kevin Costner movies, a subject for gossip columnists. The great theorist of camp had become an objet de camp. New York’s intellectual life hasn’t been the same since.

The critic Irving Howe—Jewish, socialist, and reverent toward T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, and the other modernist masters of the twenties and thirties—perfectly represented the old style. By the late sixties, he joined Partisan Review founders William Phillips and Philip Rahv in despairing about the trajectory of American politics and culture. Howe believed that his colleagues in the intelligentsia bore a large part of the blame for the culture’s new vulgarity. At the end of that decade, he put down these thoughts in a piece for Commentary called simply “The New York Intellectuals.”

As he looked back on the world of his youth, Howe waxed both nostalgic and dyspeptic. He celebrated the old-world innocence of West Side intellectuals (“the immigrant milk was still on their lips”) and their achievements (“to the minor genre of the essay the New York writers made a major contribution”). But the old intellectuals had run their course and dissolved in disarray—“unhealed wounds, a dispersal of interests, the damage of time.” He lamented that they had been replaced by a younger generation of critics who brought along what they called a “new sensibility.” Although Howe couldn’t precisely define this new sensibility, he knew how to define the new enemy: Its name was Susan Sontag. The essay piled attack upon attack. “Susan Sontag [is] a publicist able to make brilliant quilts from grandmother’s patches.” In her writings, Howe argued, old modernist ideas reappeared in swinging-sixties lingo, although she had managed to sap them of complexity and genuine critical edge. She represented a “highly literate spokesman” for those “who have discarded or not acquired intellectual literacy.”

Howe’s ill will sprung from substantive disagreement with her aesthetics. But his harsh rhetoric bears the marks of sharp feelings of betrayal. Indeed, Sontag had initially arrived in New York in 1959 with the hope of joining Howe and the Partisan Review intellectuals, not upending them. Sontag’s friend Steve Wasserman, the editor of the Los Angeles Times Book Review, says that she first discovered Partisan Review as a 14-year-old girl at the International Newsstand on Hollywood Boulevard. “She told me that she took the issue home and found it utterly impenetrable. Somehow she came away with the feeling what these people were talking about was of the most enormous importance, and she was determined to crack the code.” When she moved to the city in her mid-twenties, living as a single mother—by way of Chicago, Boston, and Oxford—she encountered Partisan Review editor William Phillips at a party.

“How do you write a review for Partisan Review?”“You ask,” he replied.

Sontag’s friend William Phillips lamented, “A popular conception of her had been rigged before a natural one could develop.”

“I’m asking.”

She quickly became Partisan Review’s theater critic, a chair formerly occupied by Mary McCarthy, who in many respects was the anti-Sontag, a popular novelist who still hewed to the magazine’s highbrow religion.

Almost every male New York intellectual of a certain age can recount with precision the first time he saw Sontag’s figure, even if it was a fleeting encounter. “I met her at Columbia in the sixties and we exchanged pleasantries,” Victor Navasky told me. Many men can recount such encounters, because for all the books and essays Sontag produced, she was a famous procrastinator, who logged many late nights and turned into somewhat of a downtown party fixture. She became enough of a presence at the Factory that Andy Warhol filmed her in a screen test. Even into her late sixties, she ran the book-party circuit, and would cross the rope line with the likes of Lou Reed and Ethan Hawke. (Sontag once joked that her son, David, spent his childhood sleeping on piles of coats hurled onto beds by her fellow partygoers.) “Susan didn’t turn down invitations,” one friend recalls. In part, she leaped into the scene with enthusiasm as a release from her stifling marriage to Philip Rieff. And in part, she leaped because she hadn’t discovered her social prowess until her twenties. “I remember once walking in Paris,” Sontag’s friend Edith Kurzweil told me. “She said that she hadn’t realized that she was attractive until very late.”

But what made her entry into this world so noisy wasn’t just her physical presence. It was the way she transgressed so many of its first principles. During the fifties, the New York intellectuals, with the critic Dwight Macdonald taking the lead, had protested against the “lords of kitsch” and the conformist mass culture that settled over the country in the postwar years. In addition to hating the “masscult,” they despised “the midcult,” that is, the schlocky art masquerading as high culture—or, in Macdonald’s words, “the enemy outside … the swamp.” Macdonald’s venerable target list included the Museum of Modern Art, the novelists James Gould Cozzens and John Steinbeck, as well as magazines like The Atlantic and Harper’s that gave regular aid and comfort to the fifth columnists of midcult. If art wasn’t seriously highbrow, then it wasn’t worth taking seriously. As Sontag later wrote in The New Yorker, she had initially conformed to this sensibility, too. After a fight with her then-husband, Philip, in the mid-fifties, she went to see Rock Around the Clock in Harvard Square: “After the movie I walked home very slowly. I thought, Do I tell Philip that I’ve seen this movie—this sort of musical about kids, and it was wonderful, and there were kids dancing in the aisles? And I thought, No, I can’t tell him that”

Even before Sontag wrote her 1964 essay “Notes on Camp” and Against Interpretation, New York intellectuals had begun to collapse this strict cultural hierarchy. Robert Warshow had written about the movies for Commentary, where he questioned whether critics were entitled to claim a perspective any more Olympian than the average fan. Leslie Fielder played in the sandbox of popular culture, writing about comic books and horror films. Macdonald wrote about film for Esquire.

But it was Sontag who struck the biggest blow. She told the New York intellectuals to open their eyes to the world around them—photography, dance, as well as Pop Art and mass culture. She also told them to loosen up and to absorb art with the full arsenal of their senses, not just their intellects. “What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more,” she wrote in Against Interpretation. By embracing “the erotics of art,” she captured the sexual revolution and turned it into an aesthetic theory.

In the harsh but richly reported 2000 biography Susan Sontag: The Making of an Icon, Carl Rollyson and Lisa Paddock found a paper trail showing that Sontag initially wanted to publish “Notes on Camp” in a glossy mass-market magazine called Show, to get maximum exposure for her ideas. But when that fell through, she placed it in Partisan Review. By running in the lower-circulation journal, her essay actually had a far greater effect and enraged far more of her comrades. Philip Rahv and William Phillips quarreled over Sontag in splenetic letters, according to Edith Kurzweil, Phillips’s widow and another PR editor. Rahv wrote to Mary McCarthy in 1965 and sniped, “Susan Sontag. Who is she? … Above the girdle, the girl is square.”

It’s easy to read this hostility as sexism. (Mary McCarthy, to be sure, was as condescending as any male critic, calling Sontag “the imitation me.”) But more than reacting to her sex, they were reacting to her sensual aesthetic. The New York Jewish intellectuals were hardly sexually well-adjusted men, a tendency that Woody Allen, Saul Bellow, and Philip Roth would pillory, and embody, until it became a sitcom cliché. What’s more, they had spent the immediate aftermath of the Second World War maturing from radicals into celebrants of bourgeois democracy, a transformation many of them announced to the world in Partisan Review’s 1952 patriotic symposium on “Our Country and Our Culture.” Good believers in bourgeois society, they argued that it was wrong, in Howe’s words, to “entrust ourselves entirely to the beneficence of nature, or the signals of our bodies, as a sufficient guide to conduct.” Or as Rahv moaned in 1965, “Middleclassism à la Trilling is out, perversion is in.”

This split had begun as an aesthetic one, but it inevitably acquired a political dimension. Sontag’s thinking neatly gibed with the emerging New Left—a political movement that Howe and the other New York intellectuals despised for its crude “Up Against the Wall, Motherfucker” sloganeering as much as for its actual positions. That’s not to minimize the political differences. Sontag had joined with intellectuals like Jason Epstein, Andrew Kopkind, Noam Chomsky, and others who clustered around the newly created New York Review of Books in questioning the anti-communism of the Partisan Review crowd. When they made their case, they sounded intentionally disrespectful of liberal values and America. Sontag, who returned from Cuba and North Vietnam claiming to have seen the future, wrote in 1969, “Imperialist America is also Babbitt America. To us, it is self-evident that the Reader’s Digest and Lawrence Welk and Hilton Hotels are organically connected with the Special Forces’ napalming of villages in Guatemala this past year.”

Words like these earned her the eternal enmity of the right, which made Sontag-bashing one of its favorite pastimes. They also provide the context in which many readers understood her notorious post-9/11 “Talk of the Town” entry, where she asserted that the Al Qaeda attacks were “undertaken as a consequence of specific American alliances and actions.” In the end, those words would seal her final alienation from the magazine that created her.

A year after 9/11, William Phillips died. His friends arranged a memorial service for him on the West Side at the New York Society for Ethical Culture. In addition to publishing “Notes on Camp,” Phillips later took even more credit for shaping Sontag’s reputation, telling friends that he had “taught Susan how to write.” But where Sontag had turned hard-left in the sixties, Phillips had followed the more conventional Partisan Review career path, moving to the right, just a few paces behind Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz. At the service, Sontag sat near the front, next to Roger Straus, and listened to loving tributes to Phillips delivered by Cynthia Ozick, Morris Dickstein, and Norman Podhoretz. Describing Phillips’s editorial triumphs, the eulogists couldn’t avoid returning to Sontag’s “Notes on Camp.” These references caused the room to keep looking toward her in her prominent seat. Yet, to the surprise of the crowd, Sontag was not displaying pride or mournful sadness so much as acute discomfort. She shifted in her chair. A glower dominated her face. A rumor began circulating in the room: Despite the constant references to her—and despite having asked for time at the lectern—she had been strangely omitted from the program. According to Edith Kurzweil, who organized the occasion, the gap between Sontag and Phillips had become too wide to justify her inclusion on a short speakers’ list.

It was easy to attach a metaphorical meaning to the moment. Sontag had contributed one of the most important essays in the history of Partisan Review. But she had also traveled far beyond the magazine’s comfort zone and helped destroy the world it represented. When Kurzweil later called Sontag and asked her to contribute to the final issue of Partisan Review—an issue dedicated to the memory of William Phillips—Sontag turned her down. “She blew up at me,” Kurzweil recalls.

Susan Sontag, a passionate cineaste, would see almost anything projected onto the big screen, no matter the brow level, true to her earliest celebrations of popular culture. And, just as Against Interpretation dictated, she could respond with emotion. Christopher Hitchens recounts an evening spent with Sontag discoursing at great length on the emotional power of E.T., so strong that it brought her to tears. “If you go to Mr. Spielberg’s movie and you are a mammal, you will cry,” she told Hitchens. “Something in this ridiculous rubber-duck figure brings out the mammalian in you.” But Sontag’s passion for popular culture has been somewhat exaggerated in retrospective accounts of her work. She didn’t own a television. Aside from early essays on science-fiction movies and pop music, she wasn’t anything remotely like Andrew Sarris or Pauline Kael, the generation of critics who followed her, constantly applying their highbrow minds to the explanation of Hollywood pleasures. Mostly, she celebrated experimental foreign auteurs—Godard, Ozu, Bresson—not exactly generators of the images regularly consumed by most Americans.

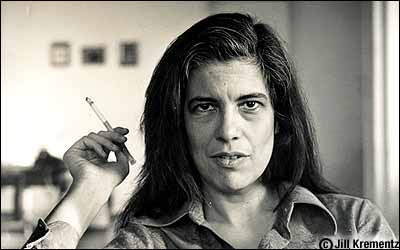

But it’s right to think of her as connected to pop culture. That’s because her visage, and her salt streak of hair, became a part of that culture. Over her career, she sat for portraits by Irving Penn, Philippe Halsman, Robert Mapplethorpe, Diane Arbus, Peter Hujar. In the mid-sixties, Joseph Cornell couldn’t resist arraying her face in one of his boxes, The Ellipsian. Sontag’s long (sometimes stormy) relationship with the camera fittingly culminated in an actual romance with Annie Leibovitz, the ultimate celebrity portraitist.

Photography obsessed Sontag and became the subject for two of her best books. Her preoccupation with photography is the single clearest example of her shifting a previously disregarded mass medium into the realm of acceptable highbrow discussion. The photograph, in her view, had changed the mechanics of memory. Our minds, she argued, no longer stored narrative; they stockpiled images. “The problem,” she wrote in Regarding the Pain of Others, “is not that people remember through photographs, but that they remember only photographs.” And in a way, that sentence anticipated her obituaries, which dwelled at length on the many photographs of Sontag.

Reviews of her books also cited her media image, and not often kindly. In an essay on her novel Death Kit, Ted Solotaroff wrote, “Like the celebrity that Miss Sontag appears to court with her left hand and disclaim with her right, her critical stance somehow managed to be both matter-of-fact and outrageous: a tone that gets under the skin in much the same way that those dust-jacket photographs of her—poised, striking, vaguely sinister—either seduce or repel.” As the Solotaroff review reveals, quite a large number of New York intellectuals were repelled. Even her friend William Phillips lamented, “A popular conception of her had been rigged before a natural one could develop.”

Sontag was hardly the first American intellectual to receive this attention. Time had devoted pages to the work of fifties sociologists like David Riesman, packaging their images and writing for the magazine’s massive postwar readership. But they were portrayed in bow ties, fusty caricatures without the movie-star qualities that photos of Sontag projected. (Not surprisingly, writings about Sontag endlessly invoked the ghost of Marilyn Monroe.) And the New York intellectuals had a rather stringent set of mores about their self-image that flowed from their hatred of masscult. As Howe put it in his 1969 essay, his generation had worried that publication in The New Yorker or Esquire was a “sure ticket to Satan.” They lived in a cloistered world. Howe wrote: “[P]recisely the buzz of gossip attending the one or two sometimes invited to a party beyond the well-surveyed limits of the West Side showed how confined their life still was.”

By the time photos of Sontag began to grace Vogue and Mademoiselle, the old taboos had started to fall away. Norman Mailer had published Advertisements for Myself in 1959, and ten years later ran for mayor of the city as a gonzo gesture in the same unabashedly self-aggrandizing mode. In his 1967 memoir, Making It, Norman Podhoretz exposed the intelligentsia to be fraudulent when it pronounced its disinterest in power, money, and fame. “Every morning a stock-market report on reputation comes out in New York,” Podhoretz wrote. “It is invisible, but those who have eyes to see can read it… . Was so-and-so not invited by the Lowells to meet the latest visiting Russian poet? Down one-eighth… . Did Partisan Review neglect to ask so-and-so to participate in a symposium? Down two.”Sontag could be self-conscious about her image. At a PEN dinner in the late eighties, she once sat next to an editor from Doubleday who turned to her and asked, “So, how long have you been in New York?” She replied, “You don’t know who I am?” A few minutes later she angrily left the dinner. The writer Edmund White, with whom she had a bitter falling-out, wrote a thinly veiled historical novel about Sontag, Caracole (1985), in which he nastily portrayed her as needy for this sort of public recognition. But she could be as disdainful of ambition as any old-time New York intellectual. While Podhoretz admitted to caring about money, Sontag sincerely showed no such concern. When cancer first struck her in the seventies, she didn’t have health insurance. New York Review of Books editor Robert Silvers organized a fund-raising campaign that scraped together $150,000 to cover the bills. Hitchens remembers that when a fire left her apartment open to the weather, she didn’t have enough money in her bank account to check into a hotel. Only in the eighties did friends push her to obtain a literary agent, Andrew Wylie, who could prod editors into forking over amounts closer to Sontag’s market value.

Even those who champion her exegetical and critical brilliance concede that her mainstream celebrity could be traced back to a combination of good looks and glamorous avant-garde flair. Credit also gets meted out to the public-relations genius of Roger Straus. It’s not a coincidence that Tom Wolfe—another celebrity writer with a trademark dust-jacket look—was another Straus author. (“PR stands for something other than Partisan Review,” Hitchens says.) And there’s another reason Sontag became so famous: She had boosters in the middlebrow institutions that Macdonald and Clement Greenberg so disdained. Time wrote about “Notes on Camp” upon its appearance in Partisan Review; The New Yorker profiled her. Given recent debates over the demise of the public intellectual, this coverage shouldn’t be quickly dismissed. They brought Sontag a much wider readership than anyone of Howe’s generation had known. On Photography sold 40,000 copies in hardcover, reaching best-seller lists; Illness As Metaphor did at least as well. Not too shabby for works of criticism.

The middlebrow media embraced Sontag near the height of its influence in the mid-sixties. It has been imploding ever since. During the seventies and eighties, important middlebrow bastions like Saturday Review and Life folded. Time’s authority dwindled; it spends far less time translating highbrow. Similarly, Harper’s and The Atlantic aren’t as deeply implanted in American homes as they once were.

Middlebrow may have been mind-numbingly earnest, and it may have lacked the critical faculties to consistently distinguish the worthy from the shoddy, as Macdonald and Greenberg charged. But middlebrow magazines treated intellectuals respectfully, even reverently, so much so that they actually paid attention to their thoughts and writings.

In the new media constellation, without any robust middlebrow presence to mediate the interactions between intellectuals and the public, high and low mingle much more freely. Intellectuals have been annexed to the celebrity culture, which deems them most worthy of attention when they have acquired a supermodel as arm candy or bitch-slap a hostile reviewer at dinner. Sontag suffered this fate. She earned gossip-column mentions for her relationship with Annie Leibovitz—and then when the New York Post accused of Leibovitz of cuckolding Sontag with the nanny caring for Leibovitz’s daughter. Even though many of Sontag’s close friends don’t know many details about the relationship, bloggers and activists flew into high dudgeon when obituaries omitted any mention of Leibovitz.

In the eyes of most Americans, Sontag became a vaguely meaningful reference in movies like Bull Durham and Gremlins 2. Sample line of Gremlins’ poetic homage, written in free verse: “Civilization, yes. The Geneva Convention, chamber music, Susan Sontag … we want to be civilized.”

Camille Paglia, the soi-disant wild woman of nineties academe, has carefully studied Sontag’s image, and wrote an essay on the subject, “Sontag, Bloody, Sontag.” This was no mere intellectual exercise. She intended to use Sontag as a career model—to discern pop culture’s reasons for celebrating Sontag and then exploit her findings to launch herself to similar stardom. “I’m the Sontag of the 1990s—there’s no doubt about it,” Paglia claimed in one of her typical bouts of modesty. Following Sontag’s lead, she let fly a string of provocative arguments, praising prostitution and announcing a new school of “drag queen feminism.” (Hard to camp it up more than that.) Working through “Page Six” and Entertainment Weekly, she attempted to bait Sontag into a fight, taunting her as “the heavyweight who used to be the bully on the block.”

For the most part, Sontag resisted these entreaties and turned away from Paglia’s stunts. “We used to think that Norman Mailer was bad, but [Paglia] makes Mailer look like Jane Austen,” Sontag said in the Sunday Times of London. It was telling that Sontag felt such chilliness toward Paglia. Over the last two decades of her life, Sontag became an eloquent critic of the culture’s turn away from “seriousness,” its relinquishment of Partisan Review high-mindedness for Paglia-like frivolity. She began to worry that her writings may have played an unwitting role in this change. In the 1996 introduction to a new edition of Against Interpretation, she wrote, “What I didn’t understand (I was surely not the right person to understand this) was that seriousness itself was in the early stages of losing credibility in the culture at large, and that some of the more transgressive art I was enjoying would reinforce frivolous, merely consumerist transgressions. Thirty years later, the undermining of standards of seriousness is almost complete, with the ascendancy of a culture whose most intelligible, persuasive values are drawn from the entertainment industries.” Irving Howe and her most persistent critic, Hilton Kramer, had been lobbing this very complaint against her for many years. Indeed, Sontag’s later critical work dwells on the matter of seriousness at such length that the only critic to invoke it more is New Criterion culture scold Kramer.

The trajectory of Sontag’s thought can be difficult to make out. “She went through phases, like a pendulum,” Victor Navasky says. It’s easy to think this about her politics and to clock her swing from one provocative stance to the next. In the sixties, she condemned America for its gaucheness; in the eighties, she turned anti-communist; then, after 9/11, her New Yorker piece seemed to show a reversion to New Leftism. But, in the end, the 9/11 essay might best be regarded as an anomaly. The piece irreparably damaged some old friendships—Leon Wieseltier never spoke to her again—and even caused her to quarrel with her son, the writer David Rieff. Other friends maintained relations with her by proffering rationalizations for the outburst. They say that she wouldn’t have seemed so heartless if she hadn’t witnessed events from afar in Berlin. Indeed, there’s evidence that she came to regret the 460-word piece. In interviews, she refined her argument, nearly to the point of retraction. She told Salon a month after the piece’s publication, “I’ll take the American empire any day over the empire of what my pal Chris Hitchens calls ‘Islamic fascism.’ I’m not against fighting this enemy—it is an enemy and I’m not a pacifist.”

This statement might not quite put her in Hilton Kramer’s camp, but nevertheless finds her not far outside of it. In fact, a closer inspection of her politics reveals that over time they grew considerably less Marxian and more genuinely liberal. Aryeh Neier, head of the Open Society Institute, watched the transformation up close. He saw how, under the influence of Eastern European émigrés like Joseph Brodsky, she came to recognize the horrors of the communist system. During the eighties, he watched her mount a vigorous campaign of solidarity with Salman Rushdie as Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa sent the Satanic Verses author underground. She publicly supported Rushdie at a time when Norman Mailer and Arthur Miller shied from protesting the fatwa on Good Morning America. Finally, Neier argues that the humanitarian interventions of the nineties gave Sontag new appreciation for American power. In 1993, Sontag famously sojourned to besieged Sarajevo, producing performances of Waiting for Godot and living in a bone-cold Holiday Inn with bombed-out rooms and sniper fire spraying into windows. Neier claims, “There’s no question that she had become a liberal—and that’s how she thought of herself.”

In other words, her political story is less like a pendulum and, strangely, more like the rightward drift of her old colleagues from Partisan Review. Of course, an enormous gap separated Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz from her—although Sontag, as a University of Chicago undergrad, did have a healthy interest in the neoconservative guru Leo Strauss. Where they became blind partisans, Sontag never relocated to another political movement. But like them, she looked back with discomfort at her younger self. She also followed them in acquiring an admiration for bourgeois democracy—the common ground she and her son shared when they forcefully made the case for intervention in the Balkans.

Whenever Sontag changed course and reconsidered a position, it was often greeted as mere posturing or the annoying tendency of a fashionista jumping on the next intellectual trend. “A Writer Who Begs to Differ … With Herself,” the Times headline of a Michiko Kakutani review of Regarding the Pain of Others quipped. Sontag was never permitted the luxury of sincere self-revision that the preceding generation of New York intellectuals enjoyed. The ur-critic of photography might have anticipated this fate. As she repeatedly pointed out, modern human beings, a group that presumably includes her highbrow comrades, remember the past as a series of images. Sontag, such an appealing and ever-ready target for the camera, survived flash-frozen in a fixed generational pose. She could never escape those Arbus and Penn spreads from her youth—radical, radically chic, fiendishly engaged in Pop Art—images that supplanted the more complicated narrative of her life. On Photography, written nearly three decades ago, made this point in a memorably wistful tone:“Today, everything exists to end in a photograph.”