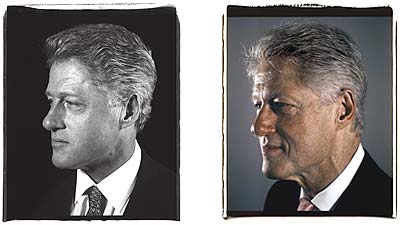

There’s a tangible, almost merciful way that the postpresidency agrees with Bill Clinton. Here in Africa, where he’ll be spending the next seven days, he’s relaxed, smiling, pink. On the first night of our trip, in a faded old colonial hotel in Mozambique, he comes bounding to the dinner table in bright-white pants, a bright-white shirt, an almost-as-white sweater (knotted around his shoulders), and brand-new canary-yellow running sneakers, like some Queer Eye project gone cheerfully awry. I will soon discover that these running sneakers perfectly match one of his ties—he’s brought a whole array of pastel cravats for the Southern Hemisphere.

“You guys ordered already, right?” His appetite is back. He’ll shortly be plunging his fork into everything. “Hey, girl.” He gives my shoulder a squeeze.

And as soon as he’s seated, Clinton launches into stories. He’s a furious chatterer, talking in uninterrupted spurts; interjections are difficult, rejoinders impossible. His unscripted conversation is a combination of highbrow and bawdy, shrewd and reassuringly profane. It’s also Arkansan once again—over the course of this week, I will hear “It’s the darnedest thing,” “I wouldn’t take a nickel to see the cow jump over the moon,” and (my favorite) “That guy’s lower than a snake’s belly,” among other regional aphorisms. During appetizers, he throws in an impersonation of Natan Sharansky’s reaction to a proposed withdrawal plan from Gaza:

I come from the biggest country in the world to one of the smallest countries in the world, and you vant me to cut it in half? I don’t sink so.

“Natan,” Clinton tries to plead. “You were not in the biggest country in the world. You were in a jail cell this big.” He extends his arms, approximating the dimensions.

I don’t sink so, Natan repeats.

Today, one could say the former president has the best of both worlds: He still visits with heads of state everywhere he goes, yet “there are no earthshaking adverse consequences,” as he puts it, if he declines to take up a cause. Though he no longer flies on Air Force One, private jets don’t seem to be in short supply. (For this particular trip, Issam M. Fares, the business magnate and deputy prime minister of Lebanon, lent us his private jet, a fabulous flying wonderland of retro suede recliners, wood paneling, and mirrors—one half expects Austin Powers to pop out of the loo.) He still stays in the finest hotels, yet he’s also regained some measure of privacy: In Zanzibar, two young women in bikinis, each roughly proportioned like Jessica Rabbit, spot him as he wanders by the pool and leap out of their chaise longues to chat. He loves it, lingers. Could he have done this before, without the tabloids wrenching some double-entendre headline out of the moment? One gets a perspective now that Ken Starr’s cloying legion of moralists could never fully appreciate: To Clinton, the world’s a seascape of temptations. And the hip-shaking sensuality of the pageantry here—so awkward for other world leaders they haven’t a clue where to put their eyes—seems perfectly of a piece with who he is.

“I loved being president,” Clinton tells me later that night. “I’d have done it again if there hadn’t been term limits, until the people threw me out. But now, I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve woken up and said, ‘Gosh, I wish I were still president.’ I just don’t do it anymore.”That may be so. But to come from nothing and become president of the United States, a person has to be metabolically preposterous, a freak cluster of aspirations and desires and appetites. To assume that this hunger would fade away after the presidency is naïve. In Kigali, Rwanda, I watch Clinton spend three minutes trying to coax a smile out of a long-faced child with AIDS; he simply will not leave until he’s managed to do so. In Lesotho, he jumps out of the car as we’re headed to the king’s palace and starts grabbing people’s hands. Why? For the simple joy of the contact? Because he’s still running for something?

Clinton is still a man of huge public-service aspirations. He’s still adored abroad. And he’s still considered president by the nation’s estranged, bluer half. Yet he’s also still deeply wounded, burdened by a sense of both underappreciation and unrealized promise. Much more than his successor, Clinton understood exactly which direction the world was headed when he twice took the oath of office, yet he didn’t, for reasons both circumstantial and of his own unlovely making, deliver some of the things he valued most: universal health care, a shored-up system of social security, energy independence, security at home and in the Middle East. He can’t rest on his laurels. So what does a man do with all this feral hunger—to do more, to set the record straight—and all this hurt, God, so much hurt, which steams off him with such intensity it practically blurs the air?

“I figured, Well, I have great relations with most leaders of the world,” he says, as he sits on the deck of his presidential suite in Zanzibar, stares at the ocean, and explains the most important piece of his new life—his AIDS work, which he’s been promoting here all week. “I think I can talk people into, you know, doing the right things. I figured if we could cut the cost of drugs, we could save a lot of lives in a hurry.” He chomps on an unlit cigar. “I really believe this is the worthiest thing I could have done as the main initiative of the administration at this point in history.”

Administration?

“Not administration,” he quickly corrects. “Foundation.”

Five years after his presidency, Clinton still thinks like a world leader. In some ways, it’s more complicated: He thinks like the leader of the world. While there’s no official means to be president of the planet, other than as U.N. secretary-general—a prospect constantly floated by Clinton supporters, though it’s practically impossible—he certainly seems to be trying hard to invent one. On September 15, the former president will be hosting the grandly titled Clinton Global Initiative, a conference timed to coincide with the World Summit at the U.N. The guest list features an impressive and eccentric mix of moguls, heads of state, and problem-solvers—from Sonia Gandhi to George Soros to Rupert Murdoch—who, after three days of panel-going and furious rubber-chicken consumption, are expected to sign pledges to do something about bettering the world.

At least, that’s the theory. It’s possible the conference won’t look very different from Davos, Aspen, the Renaissance Weekend, and other high-end policy huddles. “They’re still trying to figure out how not to make this another yak-yak,” says Mike McCurry, the former Clinton press secretary. The cost of attending the CGI, $15,000, has also raised more than a few eyebrows, considering so much of it dwells on eradicating poverty (Clinton’s people say the fee will be waived for those invitees who can’t afford it). And because this is Clinton we’re talking about, it’s likely the program will be in chaos until the curtain comes up. Organization isn’t exactly his strong suit. “He’s … flexible,” says Bob Dole, the former Senate Republican leader and Clinton’s presidential challenger in 1996. “He’s almost loose.”

But never mind: For the former president, it’s finally a chance to press forward, to shore up his legacy—to throw an inaugural ball, really, for his third term. Before this moment, Clinton hadn’t had a career so much as big projects to complete: millions in legal bills to pay off; a $180 million library to design, curate, and pay for (it’s still not paid for); a $10 million autobiography to write; and, most unexpectedly, two heart surgeries from which to recover.

No longer. Clinton, the man people accused of trying to be everything to everyone, can now embrace just that role, recasting himself in purely global terms. Since leaving the White House, he has traveled to 67 countries. On this African sweep, he manages to squeeze in six in seven days. “I think there are three people who are universal, whose prestige truly extends way over borders,” says Hernando de Soto, the Peruvian economist and author of The Mystery of Capital (and a key participant in the CGI). “There’s Nelson Mandela, Kofi Annan, and Clinton. The problem with Kofi is that he leads the world’s biggest bureaucracy. And Mandela is basically an African. He’s never had something to say about Asia. He’s never said, ‘I like mambo.’ Strangely, the only one who does this is Clinton, and he doesn’t even speak a foreign language.”

He pauses. “I mean, say Jacques Chirac retires,” says De Soto. “He can’t do the Chirac Global Initiative.”

The question is, how will Clinton translate his own iconic status—not to mention his considerable intellect and political skills—into something concrete and influential that goes beyond this conference? The Jimmy Carter good-works model comes closest to what appeals to Clinton, but that’s not exactly right; Carter is far less dynamic, and when he first left office, he had little international or domestic clout to exploit. “The contrast is interesting,” says Harold Varmus, the former director of the National Institutes of Health. “Carter’s done great work. Yet it somehow comes across as prissier.”

Like Carter, Clinton has a foundation dedicated to good works. But it has attracted only intermittent attention at home, constrained as Clinton is by a shoestring staff (his foundation’s non-AIDS budget is just $6.5 million, though this doesn’t include in-kind contributions, like the use of private jets), a wife he shouldn’t eclipse (especially if you believe in her prospects for 2008), and an American media with other, larger fish to fry (at a New York event featuring Clinton and Ted Turner in June, I was stunned by the number of unclaimed name tags that lay on the table).

Nor does it help that the former president is a bit like a bug with eyes all over his head. Though the AIDS pandemic is currently the Clinton Foundation’s highest priority, it lists many other objectives: helping small inner-city businesses, encouraging citizen service, promoting religious reconciliation, curbing childhood obesity, fighting global warming, alleviating global poverty through empowerment measures. As a result, Clinton’s postpresidency has yet to become synonymous with anything. It’s as if we’re back to the opening days of his administration, when the aides were young, bright, and large-hearted; pandemonium reigned; and the president, eager to do everything, didn’t quite seem to stand for anything.

“I don’t think something’s not worth doing just because I can’t spend a lot of time on it, particularly if I can leave something good behind,” says Clinton, who’s particularly sensitive to this charge. He lists, as examples, the American India foundation he started in the wake of the Gujarat earthquake in 2001, and the tsunami relief he did with Bush 41 and the U.N. “If I hadn’t done any of those things,” he says, “I cannot honestly say that we’d be further along than we are with AIDS, because there’s only so much of the technical stuff I do.”

Which may also be true. Like Clinton, who turns 59 this week, his postpresidency is still young, and no one can say his AIDS efforts are dilettantish or unimpressive. After three years, his foundation has helped put 170,000 people in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean on anti-retroviral treatment, which may sound like a small number, but in fact (appallingly) accounts for roughly 20 percent of the people receiving anti-retroviral treatment in developing nations.

“What Clinton has to do is find a way of organizing his influence,” says De Soto. “But for us in the Third World, we don’t see that as a problem. We’re continually inventing things. Ask Vladimir Putin whether his political party existed eight years ago. Ask any African leader whether his party existed ten, fifteen years ago. What an individual can do in the United States is limited compared to what an individual can do abroad. So I told him, with all due respect to the presidency, that I think he can be a bigger historical figure in his postpresidency—if he plays his cards right.”

“Watching him today, with the self-assurance he has with foreign leaders and the knowledge of the world he’s acquired, it’s impossible not to think, Oh, if only he’d known all that when he was president,” says Richard Holbrooke.

On a blue, sunshiny day in Johannesburg, Clinton meets Nelson Mandela for lunch at his home. It’s more modest than one would expect, pretty and mustard-colored with a surprisingly low wall surrounding it, though it’s deceptively well defended by other devices, including an intricate nest of security cameras. Before Clinton heads inside, Mandela comes out to greet us—perhaps a contingent of a dozen or so—and looks, still, as if he’s never been through the world’s most pointless and unimaginable horrors. His eyes shine; his face is as unlined as a stone. Like Clinton, he’s fast with a rejoinder, capable of putting everyone at ease (a good thing, since a fair number of people who meet him spontaneously burst into tears). When greeting the woman in front of me, who Clinton informs him is from Chicago, he smiles with evident delight. “Chicago!” he says, shaking her hand. “How is Chicago? How is Oprah?” Clinton bursts out laughing. The two head inside for lunch.

Abroad, Clinton draws much simpler reactions than he does at home, affection generally uncomplicated by ambivalence. As the Lewinsky scandal garishly unfolded, Clinton spent a lot of time abroad, including eleven days in Africa. When Mandela later accepted the Congressional Gold Medal, he swept to the president’s rescue with a subtle and eloquent defense.

“Africans saw it for exactly what it was: an abuse of power,” Clinton tells me. “They got it here. And all across the world.” Seven years later, the ordeal of his impeachment still has a vibrant, ever-present life in Clinton’s mind. “During that time, a lot of world leaders would ask, What is going on? Is this serious? That kind of stuff. I kept assuring them that nothing bad had happened to America, but that we periodically went through”—he rummages for a word—“spasms.”

At home, Clinton also has another problem: To involve himself too heavily in politics would look petty and small. As a rule, he refuses to bluntly criticize George W. Bush, whose political skills he considers “extraordinary” and whose father he genuinely likes. When I ask whether he enjoys playing good cop around the world to George W.’s bad cop, he punts, saying, “It’s not true that people dislike W. all over the world. In Russia, they probably like him more than they like me.” When I mention that both McCurry and Sandy Berger, Clinton’s former national-security adviser, told me that Clinton, too, would have gone to war with Iraq, he doesn’t deny the possibility, though he doesn’t confirm it either, saying, “I’m still not exactly sure what the intelligence really said. But I can tell you this: I would have asked the Congress for authority to use force if Saddam did not allow the inspectors back in, or did not cooperate with them, or we found weapons of mass destruction. Because he never did anything he wasn’t forced to do, at least in my experience.”

Only at one point in our discussion does he allow something harsh about his successor. “I always thought,” he says, “that bin Laden was a bigger threat than the Bush administration did.”

Were Clinton to engage himself in his own party’s doings, at least directly, he’d also have problems—namely in stirring up resentment. This is precisely what happened when word got out that he’d told Good Morning America that the Democrats needed a Social Security plan of their own. Before he knew it, his phone was ringing off the hook from Democratic congressional leaders: Did he have any idea what would happen if they proposed a Social Security plan when the Republicans hadn’t even done so?

But the most powerful incentive for Clinton to concentrate his energies abroad—one that dare not speak its name—is that it keeps him out of the media spotlight, and instead keeps it shining on his wife. “Obviously, he’s not going to say anything that causes Hillary a problem,” says Dole. He reconsiders. “And if he does, he’s not going to say it more than once.”

Clinton claims, rather dubiously, not to think about Hillary’s 2008 prospects very much—“I literally spend as close to no time thinking about this as possible”—but at one point during our discussion, he unwittingly reveals the obvious: Of course he does.

What, I ask him, should the Office of the First Man be?

He chuckles, waves his hand. “I don’t know.”

But I’d really like to see a female president in my lifetime—

“I would too.”

Okay, so . . .

“Okay, I’ll give you a straight answer to that,” he says. Though at first, it doesn’t seem so straight. “On more than one occasion,” he says, “I have been invited to try to do things for the White House. The most visible, obviously, was to do that tsunami thing with George Bush’s father. And the most ceremonial was to go to the pope’s funeral.”

At this point, I interrupt and ask if he’s misunderstood my question: I was asking what the Office of the First Man should be, not the role of an ex-president. “I’m coming to that,” he says. “So I think if there were a president in my party again, no matter who it was, and I was asked to do anything, I would do it. And obviously, I feel Hillary gave me all those decades and was unbelievably good, in a thousand ways, and made a real difference to my public service. So if she asked me to do anything, I would do it.”

If she asked you to do anything, you’d do it, I repeat.

“Anything,” he answers.

Without realizing it, Clinton had answered my general question with a very specific answer. What should the Office of the First Man look like? Whatever Hillary wants it to.

Clinton has decided to take a spontaneous stroll in Stonetown, a coastal trading center in Zanzibar. Whenever he does something like this, it makes his security detail, now considerably diminished, go slightly nuts. Startled residents begin to follow him by the hundreds, choking off the town’s coral alleyways; merchants line the narrow sidewalks, beckoning him into their shops. The Secret Service forms a compact solar system around us, appraising our strange surroundings: The streets are labyrinthine, and there are open balconies everywhere. Complicating matters, Clinton is wearing a bright-white pair of pants and a pylon-orange polo shirt. He might as well be wearing a bull’s-eye.

The former president, naturally, looks oblivious to the potential hazards of the situation. The locals are repeating the same plea—“Your hand, sah, your hand”—hoping for a shake. He grabs as many as he can, his eyes both vacant and alert, the inevitable product of megacelebrity and a life that demands polite listening and aggressive solicitation in equal measure.

I have now seen this kind of hysteria over and over in Africa. In a health clinic earlier, nurses in purdah were whispering excitedly into their cell phones; in Lesotho three days ago, crowds lined the road the entire way from the airport to the king’s palace, the men cheering, the women ululating at the tops of their lungs. Later, Clinton was knighted. More ululating ensued.

The irony is that Clinton, when he was president, had a much less engaged relationship with this place than he did with other parts of the world. In fact, one could easily make the case that Africa was worse off in 2000 than it was in 1992. There was the genocide in Rwanda, where the president turned a blind eye and 800,000 people died in 100 days. There was a devastating war in the Congo, in which the president pursued a similar policy of non-intervention. And from 1992 to 2000, AIDS cases more than doubled in sub-Saharan Africa. Yet in 1998, he barely mentioned AIDS on his first trip to the continent.

“We didn’t want it to be a flies-in-the-eyes trip,” says McCurry. “So we focused on the emerging trends that showed where things were going well, making the argument that Africa didn’t have to be a basket case in our minds. If you focused on the AIDS pandemic, you just put Africa right back in the basket.”

Yet during Clinton’s presidency, Africa did, to his credit, come alive in three dimensions on the map, which may be the main reason Africans still love him. He made two trips here, said slavery was wrong, and forgave many African nations their debt. He also engaged Africa as he did so many developing nations—with a trade bill—which may ultimately have an even bigger impact than doubling aid to the continent, the objective of the G-8 Summit last month. “More than anything, he gave the people on the continent a sense of self-respect,” says Charlie Rangel, the Harlem congressman who first encouraged Hillary to run for the Senate. “Racism is so embedded in the world that even African leaders felt the need to get white wives.”

Back in Stonetown, Clinton is trying to help the local economy in his own small way: by shopping. “Say, look at this!” he exclaims, fiddling with a beaded, wooden object. “I love folk instruments.” He emerges from the store having purchased not just this but a bongo. He goes on to buy gourds, baskets, spices, jewelry, and wooden giraffes, forcing three of his aides to double as sherpas, humping his spoils through the streets. As he wanders back to his hotel, three men reach out simultaneously to touch him. They lean so far over, their kaffiyehs fly off their heads.

Clinton may say he loves his new civilian life, loves his new house in Chappaqua. But that doesn’t mean he’s mentally decamped from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. “I thought that if I had six more months,” he tells me, “I could make peace in the Middle East. I’d have figured out what was really keeping Arafat from saying yes.”

What was it?

“I don’t know.” He shakes his head. “But I think I would have. And I think I’d have gotten more help from the other Arabs, a couple of whom he told he was gonna take the deal.

“I also wish,” he continues, “I desperately wish, that I had been president when the FBI and CIA finally confirmed, officially, that bin Laden was responsible for the attack on the U.S.S. Cole. Then we could have launched an attack on Afghanistan early. I don’t know if it would have prevented 9/11, but it certainly would have complicated it.”

The sentiment sounds both sincere and self-justifying—both a regret and a preemptive exercise in legacy protection.

The gaffes and conflicts of Clinton’s administration, self-created and not, also still plainly cling, still sting, and so does the criticism he continues to endure, even if it’s for more highbrow policy choices. When I ask Sandy Berger how often he talks to Clinton, he answers, “Usually when he sees something critical of his foreign policy in the newspaper and wants to revisit it.” Similarly, when I ask Clinton what his first February as a civilian was like—he’d said in My Life that Februarys make him miserable—he launches into a screed about his frustrations over media coverage of his final days in office.

“I was really mad about the setup I got on the way out the door,” he says, referring to (in retrospect) a completely inane dispute about whether the Clintons had left the White House with furniture that was rightfully theirs. “It was totally bogus, totally manufactured, totally false. The people running the White House suggested we take the furniture, and I said, ‘Well, I’ll pay for it, it has sentimental value … ’ ” The story goes on and on, for what seems like ten minutes at least. “The whole thing was just one more lie,” he says, giving his cigar clipper an emphatic snap. “I was really angry.”

Did he call the Washington Post, which broke the story, to explain?

“No, I didn’t call them,” he says. “After the way they, you know … they were an extension of the special counsel’s office.”

And then, before I know it, he’s off and running on a related topic: “And the same thing was true about the pardon deal … ” Another ten minutes about Marc Rich follows.

This is the Clinton you just want to shake: the defensive Clinton, the one who can’t concede he might have had a hand in his own undoing—perhaps not in these particular instances, but in the bullheaded, fingers-in-the-ears manner he attempts to bat them away. Then again, Clinton had the peculiar misfortune of presiding over an era of prosperity—one he helped usher in, no less—which often gave a bored White House press corps little to do but write process stories, inconsequential little play-by-plays about what was happening behind the scenes, rather than policy outcomes. Their bellicosity, combined with Clinton’s relentless indignation, produced some pretty foul chemistry.

I ask Clinton why the Bush administration has gotten much softer press coverage than he did. He gives a variety of explanations, including September 11 and the rightward drift of the media. Then he gives an explanation that’s surprisingly tart: “The Bush people didn’t have anybody working for the White House who, as far as I could tell, had an inexplicable, craving need that a lot of the young people did who worked for me in that first year to talk to the press—even when they didn’t know what they were talking about.”

Wow. Kids, you know who you are.

It may be true that every former president obsesses this way. But it’s striking how hurt Clinton still is by Al Gore’s choice to distance himself from his administration’s record. “When he changed the theme of the campaign to ‘Don’t put your prosperity at risk,’ there was an astonishing closing of the gap,” he says. “He picked up like a rocket, you know. And won the race. You can go back and look. Watch the polls.”

During the 2000 campaign, Clinton says, he even suggested to Joe Lieberman, Gore’s vice-presidential nominee, that he and Gore try to use Clinton’s impeachment to their advantage. “I mean, heck, if a pollster called me and asked me if I approved of Bill Clinton’s morality based on Monica Lewinsky, I’d say no too,” he says. “But I thought this was really a great opportunity for two people who no one would ever suspect would make a personal mistake to say, to say, ‘What Bill Clinton did was wrong, but he paid for it. What the Republicans did was worse, because they trashed the Constitution. You can’t afford to give them the executive and legislative branch—because they will abuse power.’ ”

The disarray of Clinton’s party continues to rankle him. You can hear it in his voice; he’s constantly fretting to friends. When the Swift Boat ads were saturating the airwaves, Clinton told John Kerry that he should immediately call for a town-hall meeting with Bush and Cheney, so that everyone could “sit around and talk about what they did during the Vietnam War.” The campaign didn’t listen.

Why?

“I don’t know,” he says at first, then reconsiders. “But I do know that when voters hear all these attacks, they may not necessarily believe them, but they give great weight to how you deal with them.”

A big part of the GOP’s success, he ventures, “has been the increasing capacity of Republicans like Karl Rove to go after Democrats as people and as Americans.” But, he plaintively adds, “if they keep beating us with the same old strategy, we have to say it’s as much our fault as theirs.”

“I want to thank you for coming today,” says Clinton. He’s in Zanzibar at one of his foundation’s community centers for people living with HIV/AIDS. Twenty-two women and three men are sitting on benches and a giant rug on the floor. Some have brought their children. One woman has an emaciated infant in her lap. “I know,” he adds, “that it means overcoming a big stigma.”

The room is small, stuffy, humid. At first he talks simply, without tenderness even, about his foundation’s AIDS work. Then he gets much more personal.

“You know,” he says, “many of you may feel very lonely in your illness. But you should know that there are people out there in the world who think about you every day. We get some money from governments, but some of our money also comes from regular people.”

The translator converts this sentiment into Swahili. The women seem surprised to discover this.

“Back when AIDS was discovered in 1981,” he adds, “America had the worst problem with the disease. And starting about twenty years ago, I knew people personally who contracted it, and they didn’t make it. I buried them. By the time I became president, we were fortunate enough to have the medicine, so we could just give it to everybody who needed it. And we’re going to try to do the same here.”

When Clinton started his foundation, AIDS was already well-covered ground: by the Gates Foundation, the Global Fund, the World Bank, Unicef, Doctors Without Borders. But when Ira Magaziner, currently director of the Clinton HIV/AIDS Initiative, met with foreign officials, he kept hearing the same thing: No one was working on getting AIDS patients into treatment. “It was all education and prevention,” says Magaziner. “The subtext from the Western world basically was, Africans die all the time.”

In July 2002, Clinton and Mandela both spoke at the International AIDS Conference in Barcelona, where it became clear that the high cost of anti-retrovirals was killing AIDS patients in developing nations. At the time, the average cost of treatment was $1,600 per person annually. In most of the African countries the foundation was looking at, incomes averaged $400 per year.

Today, the foundation is working directly with fourteen governments on AIDS-treatment programs, using 200 paid employees and 100 volunteers. Its work varies considerably from place to place. In India, it just announced a program to train 700,000 new doctors. In Lesotho, it just helped launch a program to treat 750 kids.

But the AIDS initiative’s most significant contribution, perhaps, is having bargained down the cost of treatment to just $160 a person per year, mostly through pharmaceutical companies in India, South Africa, and China. That’s still far too much money for most Third World AIDS patients to pay, of course, but it’s cheap enough to entice their own governments to finally subsidize their care. Clinton’s AIDS initiative has also received $17 million in private donations this year, including nearly $1 million from the Elton John AIDS Foundation, and benefactors donate their private jets for almost every trip (on this one, the plane would otherwise have cost $800,000). Most important, Clinton has personally lured the governments of wealthier nations to contribute directly to the AIDS efforts of the countries with whom his foundation’s working. Ireland, for example, has just pledged $50 million to the government of Mozambique, and the Norwegians have pledged $25 million to Kenya and Tanzania.

It’s hard to underestimate the power of a Bill Clinton imprimatur in these countries. When a governor in an African nation tried to demand kickbacks for AIDS treatment, Clinton picked up the phone, and the matter was cleared up in minutes. After Sonia Gandhi’s coalition took control of India’s Parliament, Clinton called and suggested working with her; two weeks later, Magaziner was on an airplane to Delhi. When Clinton hugged an AIDS activist in China, the prime minister went to visit an AIDS clinic a few weeks later.

Two years ago, at Nelson Mandela’s 85th-birthday party—a 1,600-person extravaganza whose guest list included everyone from Bono to F. W. de Klerk—Clinton and Thabo Mbeki, the current president of South Africa, got up in the middle of the festivities, trailed by Magaziner. “They just … walked out,” recalls Richard Holbrooke, the former U.S. ambassador to the U.N. “And went into a private room.” They returned half an hour later. It was after that meeting that Mbeki, famously reluctant to even acknowledge that HIV caused AIDS, agreed to allow the Clinton Foundation to assist his government in preparing an AIDS-treatment plan. (It was adopted by the Cabinet the following November.)

Back in Zanzibar, Clinton concludes his visit to the community center with a group photo. Two kids climb into his lap and instinctively lean in when the camera snaps. “Bye,” he tells them, before getting up. “I wish I could play.”

The whole week of August 30, 2004, Clinton noticed a persistent tightness in his chest. By that Thursday, he noticed his chest was clenching even when he was at a standstill. We all know what happened after that: bypass surgery on September 6, followed by surgery for obscure complications on March 10. Clinton says that in retrospect, he was symptomatic as far back as 2001.

What were his symptoms?

“Well, uh … ” He pauses. “The one I feel comfortable mentioning is that although I lost a bunch of weight in 2001, I couldn’t run a mile without stopping and walking. It didn’t make any sense.”

Which is interesting. Though now, of course, I can’t help but wonder what symptoms he’s not comfortable mentioning.

What should the Office of the First Man look like? “Obviously,” says Clinton, “I feel Hillary gave me all those decades, and made a real difference to my public service. So if she asked me to do anything, I would do it.”

Either way, Clinton’s health, as far as I can tell, is basically restored, though his aides still beg him to slow down. He’s not jogging, but he walks four or five miles when he can, and he goes to bed very, very late (on this trip, he never retires before four in the morning). His schedule, which borders on lunacy, is quasi-presidential: He and Hillary have basically given up on connecting each weekend, though they speak every day by phone. (The one conversation I overheard sounded … utterly normal. Sorry. He was describing a golf course he glimpsed in Dar es Salaam.) When in Europe, he also tries to pop in on Chelsea, who’s doing a health-care consulting project in the London office of McKinsey & Company. (They spoke four times the day of the second London subway bombings. Clinton, sounding more like a dad than a man who used to receive daily intelligence briefings, said the terrorists were just trying to spook Londoners.)

Clinton’s Harlem office continues to hum. He receives 14,000 pieces of mail a month; the job offers keep rolling in. (Recently, he got three separate offers to do movie cameos, all declined.) He still gives three or four paid speeches per month, at anywhere from $150,000 to $250,000 a pop, though his aides say the money he receives from poorer countries goes into his foundation.

But what enlivens Clinton most, still, is clearly politics. He plumps like a sponge when discussing it. You can just tell how much it kills him to be benched. Shortly after Bush released his first budget, Leon Panetta, Clinton’s former chief of staff, recalls chatting with his old boss and listening to him try to formulate the Democratic response. “At some point,” Panetta says, “I began to think, That’s great, but I’m here in Carmel Valley, 3,000 miles away.”

Protocol dictates that former presidents, especially ones of a recent vintage, can’t spend much time in Washington. So Clinton keeps up mostly by phone: with John Podesta, his former chief of staff, who now runs a think tank; Rahm Emanuel, a former policy aide who’s now chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee; his former campaign advisers; Berger; and, naturally, his wife.

But with the exceptions of Emanuel and senators Christopher Dodd and Ted Kennedy, he doesn’t chat very much with members of Congress, unless they want his campaign advice. (For this, they call him all the time.) “Clinton didn’t leave Democrats with a new sense of mission and direction, a legacy they could build on,” says Robert Reich, the president’s former Labor secretary and one of his less bashful critics. “There was no Clinton doctrine, no Clinton approach to foreign or domestic policy. But he is one of the best political strategists in America. So how does he use his skills to the utmost? Beyond doing what he’s been doing, I only see him getting his wife elected president.”

Unlike Al Gore and John Kerry, Hillary will certainly take Bill’s advice. She already has. One can already hear it in her speeches—not just in her deft and gingerly discussions about abortion, but in the general moderation of her tone. (The day before I attend a Democratic Leadership Council event in New York where Bill is the headliner, it’s reported in Roll Call that Hillary has joined the DLC.) Unfortunately, playing consultant to his wife will, in some cases, make it harder for Clinton to play consultant to others. As Bob Kerrey, the former Nebraska senator and current head of the New School, points out, “Presidential candidates would have to phone and ask, ‘Say, have any good ideas about how I can beat your wife?’ ” He pauses for a minute, reconsidering his syntax. “Wait. Please say defeat your wife. I meant defeat.”

(Though now, inconveniently, Hillary herself has to defeat Jeanine Pirro in 2006.)

But politics is something Clinton knows, at least. What he’s doing now is improv, and he’s not quite sure where he’s going. Watching him invent his new life is fun, intoxicating, but a tad bittersweet too—sometimes he seems to be taking a mulligan on his presidency, doing the redo, and he often repeats himself, retelling almost verbatim anecdotes he’s written for My Life. His aides, like faithful spouses, have heard his stories dozens of times, and if the setting is informal, they cluster toward the end of the table and talk among themselves as he entertains. Many still wind up playing cards with him until the small hours of the morning.

These young aides are now the backbone of his life. Clinton may be treated like royalty abroad, but on this trip, he travels with a corps of just a half-dozen or so, which seems pathetically meager for a man with so many lingering ambitions. “I think he misses the ability to say ‘Do this’ and it happens,” says John Breaux, a recently retired senator from Louisiana. “He’s very impatient.”

The irony is that Clinton has never been better equipped for elected life. “Watching him today, with the self-assurance he has with foreign leaders and the knowledge of the world he’s acquired,” says Holbrooke, “it’s impossible not to think, Oh, if only he’d known all that when he was president. I feel it. Everyone feels it. He’s now operating at a level so extraordinary, you know he’d have accomplished more. But that’s life.”

Clinton is staring out the window of his SUV, the sumptuous, feminine hillscape of Kigali flying by. “A lot of the borders in African countries are just as artificial as the borders in the Middle East,” he says. “But Rwanda, as you see, is highly mountainous, so it’s basically been a mountain kingdom for 500 years … ”

“Lookie here,” he interrupts himself. “That is a big wedding.” We stare at hundreds gathered outside a brick church.

Kigali is the one place in Africa where I do not see Clinton getting a hero’s welcome. At the moment, we’re on our way to the genocide memorial. As he waves to people standing by the road, almost none wave back.

“So,” he continues, “the Hutus and Tutsis and the Twa, they’re used to working together and living together. While it’s true that they have historically had conflicts and tensions, it’s also true they’ve lived together for very extended stretches without mauling each other.”

More waving. Few responses.

“I say this,” he concludes, “because whether it’s Milosevic and Bosnia or the Hutu leaders here, you can bet your bottom dollar that whenever somebody tells you there’s an inherent religious or ethnic conflict, there’s a politician behind it trying to get power, money, or both.”

Clinton has often said that his failure to intervene in the 1994 Rwandan genocide was one of the greatest regrets of his presidency. Yet as Samantha Power meticulously chronicles in A Problem From Hell, it’s not like he felt any urgency to stop the butchery as it was occurring. During those three-plus months, he never once convened his top advisers to discuss the genocide. On April 8, the State Department held a press conference and mentioned the slaughter in Rwanda, but gave far greater emphasis to its concern over foreign-government bans of Schindler’s List. Power notes that no one, at least back then, made a connection between the two.

Clinton has certainly made that connection today. At lunch with President Paul Kagame, the Tutsi rebel who ultimately ended the butchery, he suggests that perhaps Steven Spielberg could do for the Tutsis what he did for the Jews through the Shoah Foundation—record their stories. Kagame, a surprisingly slight man with intense eyes, seems intrigued. Clinton says he’ll phone Spielberg when he gets back to New York. Then he leaves to do a foundation event on AIDS. “I’m obsessed with this AIDS thing,” he tells a local journalist. “Rwanda is so small that if we can have effective health care here, we can have a model for every country to adopt.”

Clinton, a devout Baptist, actually has a second chance in Rwanda. Eight hundred thousand people here are now infected with HIV—the same number, as it turns out, of victims who were slaughtered in those 100 days. (In fact, that number is so high in part because of all the rapes during the terror.) By helping to ease the nation’s AIDS patients onto anti-retrovirals—there are 12,000 out of an eligible 100,000 currently in treatment—Clinton may help avert another slower, more insidious form of mass extermination. And Ira Magaziner, one of the key players in Clinton’s ill-fated health-care plan, can even give them universal access to badly needed medicine.

“In retrospect, I think Clinton didn’t think we’d done enough on AIDS,” Sandy Berger tells me before I leave for Africa. “We increased money on anti-retroviral drugs and NIH research, and we talked about it as a national-security issue at the U.N., but I think, when he left … ” He cuts himself off. “You know, when you’re hurtling through the day, you don’t have a lot of time to pause and separate the urgent from the important.”

At the genocide memorial, Clinton and I get out of the car and tour the museum in two different groups. It is, as one would expect, highly moving, so understated in places it’s almost telegraphic—in one room, visitors stand in total darkness and simply listen to the whispered names of the dead. When Clinton emerges, he’s visibly moved. He points to the man who led him through. “That guide?” he says. “He lost his brother and sister-in-law. His aunt lost her husband and six children. He said 76 people in his family died. Seventy-six. And he just … does it, you know? He just took me through.”

At the end, when Alexander the Great saw there was nothing left to conquer, he supposedly wept. Clinton doesn’t seem much like a weeper. He seems more like the kind of man who’d throw a conference when business gets slow. “Every time you talk to him, you sense he misses us all sitting around the table,” says Donna Shalala, his former Health and Human Services secretary. “Lots of smart people talking, as opposed to individual conversation.”

If Clinton’s presidency couldn’t quite take us where he wanted us all to go, then his Global Initiative, scheduled for September 15 through 17, will at least allow him to explain where he meant to take us. “He’s very, very good at answering the question of what’s going on, and then connecting it to people,” says Bob Kerrey (who notes, with some regret, that he has not been invited to the CGI—yet). “He’ll say, You’re an auto manufacturer: Here’s what globalism means to you. He’ll notice, Iran’s the only country that’s had the same outcome four straight times in elections. He’ll say, Here’s what’s going on in South Africa. You may disagree with it, but he can answer.” He pauses. “I mean, I haven’t even read the paper today.”

The CGI is divided into four topics: promoting good governance, reducing global poverty, improving the environment, and religious reconciliation. Dozens of world leaders are scheduled to attend—Tony Blair, Shimon Peres, and King Abdullah among them. Because Clinton wants the conference to be bipartisan, he personally invited Rupert Murdoch and Arnold Schwarzenegger. (Condi is also attending.)

What he hopes will distinguish it from others will be its outcome. “Ideally,” he says, “if between 500 and 1,000 people actually fill out those little forms and say, This is what I’m going to do to fight poverty, in terms of investing in Gaza or helping a country abolish their school fees, or This is what I’m going to do to fight global warming—as the head of company, I’m going to save the equivalent of 100,000 cars a year on the highway … ” You can almost hear the man who came of age during the sixties speaking, until he comes up with a perfect third-way description of the event: “It’s social entrepreneurialism!” And perhaps it will be, if it works—as well as a means for him to deliver on the goals of his presidency, even if it’s after the fact. How funny that Clinton had to form a nongovernmental organization—“become his own NGO,” as he likes to say—in order to finally fulfill his promise. Then again, maybe that’s appropriate for a man who gave an elegy for Big Government in his 1996 State of the Union.

“Whenever I hear him speak,” says McCurry, “I’m struck by how he still talks about wanting the United States to emerge with noble purpose in this incredible age we’re in. It’s what he wanted his presidency to be about, but it got diverted for a number of reasons, some less savory than others. Some just because of the realities of the times.”

Perhaps that’s the loveliest thing for Clinton about being released from public office: As a politician, he was a pragmatist, but as a civilian, he’s an idealist again. Watching him in Africa, it’s impossible to feel an ounce of cynicism about his motives. He’s genuinely delighted that Kenya has abolished its school fees. He really does think that the AIDS crisis is a problem that can be solved. He could be playing golf right now. But he’s not—he’s in sweltering AIDS clinics in Zanzibar at four in the afternoon.

And maybe—just maybe—he’ll figure out a way to use this new, internationalist phase of his life as a dress rehearsal for his future and final act, as secretary-general of the U.N. When he’s 75, say. “I just don’t know,” Clinton says, stammering a bit, as he leaves the genocide memorial and heads back into his SUV. “There’s never been an American secretary-general. So you know, I just, I, I can’t imagine it would ever really happen.” He considers. “I mean, if Hillary weren’t in politics, if we didn’t have anything else to do, if I were lucid and strong, if someone really wanted me to do it, I guess I’d think about it.”

Then he jumps into the car and heads to the airport, where he’ll shortly be leaving for the Canary Islands—a seventeen-hour flight, to a place where he’ll spend a single day.

The African CampaignJuly 19

At Nelson Mandela’s home, Johannesburg, South Africa.July 19

With students from City Year, Johannesburg.July 22

Inspecting a guard of honor, Nairobi.July 22

City Primary School, Nairobi.