If you’ve been labeled a bastard, you may as well play the part. In mid-November, John Bolton, the newest American ambassador to the United Nations, issued an ultimatum: He planned to hold the U.N. budget hostage unless certain reforms he particularly coveted were made part of the deal. Even by American standards, and even from a man who once suggested the U.N. could do without the top ten floors, this was a rather startling—some might say insolent—threat. Today, just a day before Thanksgiving, his colleagues are sufficiently vexed that they’ve decided to say something about it.

“We’re not in favor of holding any individual items, or the budget, hostage to other issues,” says Sir Emyr Jones Parry, the British ambassador, to a scrum of reporters who’ve gathered outside the Security Council. He has a cautious bearing, as one might expect a British ambassador to have, and his face has the appropriately versatile, anonymous look of a diplomat. He is careful never to mention the United States, much less Bolton, by name, but it’s quite clear who and what he’s speaking about. “The EU position,” he adds, “is that we want the budget adopted in the normal way.”

“Wow,” says a veteran U.N. reporter after he walks away. “That’s the first time I’ve heard the EU tell the United States to fuck off.”

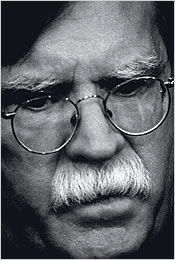

Just minutes after that, Bolton himself emerges, wearing gray pinstripes, a signet ring, and a maroon-and-gold tie so frankly unattractive it’s endearing. He’s smaller than one might expect, maybe five foot eight, but still commanding, and not just because he arrived at the U.N. brightly branded by a former State Department colleague as “a quintessential kiss-up, kick-down sort of guy.” A U.N. official had recently mentioned to me that there’s something compelling, almost Asperger’s-ish about the United States’ new ambassador, and when I see him at close range, it’s clear what he meant: Bolton is savantlike yet socially awkward, alert yet more attuned to his internal rhythms than external ones. He doesn’t make small talk. He launches straight into his remarks, which are direct and concise. He takes only a few questions, the last of which is a holiday softball: “At a time of world crises, what do you have to be thankful for this Thanksgiving, now that you’re here?”

Outside the United Nations, Bolton’s answer, highly political, would probably seem appropriate. But within its walls, at a time when the United States has turned its back on the Kyoto treaty and gone to grammatically tortuous lengths to defend its use of torture, his answer sounds strangely impolitic.

“That I’m an American citizen,” he says.

When George W. Bush nominated John Bolton as America’s ambassador to the United Nations this past March, it seemed like the president had finally found the man with the personality to match the arrogance and unpleasantness of our country’s present reputation. Bolton, a former undersecretary of State for arms control, proved unconfirmable by the Senate, and his failed confirmation hearings left a series of startling impressions, not just physical (the jowl of a basset hound, the walrus mustache of a state trooper) but characterological: He had a genius for obsequiousness, said former colleagues. A bad temper. An intolerance for dissent. Now, at this fragile juncture, Bolton was supposed to represent us at the U.N.?

Most of Foggy Bottom assumed that Bush was sending Bolton to New York because Condoleezza Rice didn’t want him in Washington. Bush had to appoint Bolton as U.N. ambassador during the August recess, when Congress was out of session. No one expects he’ll be confirmed at the beginning of 2007, when the Senate is required to try again. The shot clock is running.

So what happens when a man who appears to regard the U.N. more as a nuisance than a help to American interests is suddenly asked to show up there every morning? Especially when he knows his days are numbered?

Contrary to expectation, Bolton has not, as many feared (and secretly hoped), ground his colleagues to a pulp beneath his kicking-down shoes. Most ambassadors report the same thing about their interactions with him: He is correct, no-nonsense, even funny on occasion. He has paid nearly 125 courtesy calls to his fellow permanent representatives (or “perm reps,” as they’re called), and he’s paying them still. He has thrown a number of receptions at the American residence in the Waldorf Towers; he attends receptions, in spite of his ascetic 9 p.m. bedtime; and he mingles with colleagues in the delegates’ lounge. The first day he took his seat at the Security Council, he did not wait to be introduced, as is the custom, but went around the room and shook everyone’s hands, ambassadors and non-ambassadors alike.

“The initial reaction was startled amazement that he didn’t have horns,” says John Dauth, the Australian ambassador, and possibly the building’s funniest. “And that he was actually a highly courteous human being. There’s been a determination to see everyone, to leave no one out, and in that respect, he’s done a lot better than his predecessors—they weren’t nearly as active and engaged as this.”

Of course, Bolton has had more than enough incentive to prove his honorable intentions. To do so would both humiliate his critics and make his own life a great deal easier. The more urgent question, raised but never answered by his confirmation hearings, is what his true motives are. Has he come to the U.N. to change it? Or to lay dynamite beneath the floorboards and blow it up?

From the moment Bolton arrived, he spoke of a very particular agenda—namely, to make a nimbler, more transparent, more sensible institution out of a place that could produce the Oil-for-Food scandal, which wound up enriching Saddam Hussein by $10.1 billion, and the infamous Commission on Human Rights, a travesty of a body that includes countries with appalling human-rights records such as Saudi Arabia, Zimbabwe, and Cuba. He said he wanted whistle-blower protection, an ethics office, a secretary-general with power to actually control the U.N. agenda.

All reasonable goals, and ones that most of our allies share. Yet starting in November, Bolton deployed a staggeringly confrontational tactic to get them, threatening to hold up the U.N. budget if real reforms weren’t in place by December 31 and to allow only a three-month interim budget to slip through.

No one was happy. Yet just before Christmas, Bolton more or less prevailed, with the General Assembly signing off on a six-month budget, the rest of its funding contingent upon its progress on management reform. It was an impressive feat, but not without cost: The EU had to bear the brunt of the negotiation, and Lord knows how many more brunts it will be willing to bear in the future. The developing world, meanwhile, got even angrier.

To a significant part of diplomatic New York and Washington—rational, unhysterical people, a group not especially prone to partisan paranoia—this was simply more proof that Bolton hadn’t come to the U.N. to reform it but to emasculate it. His tactics, in their view, say it all: He tends to talk off the top of his head; to float radical ideas in small settings before modifying his rhetoric in large ones; to bargain in as ham-handed a fashion as possible, pulling back from the brink (if he ever does) only after all hell has been loosed upon the halls and his bosses in Washington have intervened to restore the peace. How could such a person be sincere about reforming the U.N.? He’ll push for it, sure, but only in ways that ensure reform never happens (artlessly, with all the subtlety of a swinging fist), rather than by pulling together logical coalitions of nations who’d favor it. Then he’ll make a great show of giving up, leave the U.N., write a book about how unreformable the place is, become a hero of the Republican Party, and run for public office.

We’ve seen some version of it before. Daniel Patrick Moynihan ran for the Senate directly after his time at the U.N., which he called “a dangerous place.” Many of these same people, in fact, believe that Bolton might not even be that interested in serving his boss—that Condoleezza Rice has far more interest in multilateralism than he does. “Bolton has his own agenda,” says Stephen Stedman, former special adviser to Secretary-General Kofi Annan. “He honestly believes that anything on paper is meant to constrain the United States, and the United States is so strong it can get whatever it wants without agreeing to constrain itself. Yet we couldn’t call Condoleezza Rice every day and say, ‘Do you know what your guy is doing?’ ”

It’s also possible, however, that bluster and brinkmanship are simply Bolton’s style—he asks for the moon because he believes it’ll help him control the tide. Abdallah Baali, the Algerian ambassador and only Arab currently sitting on the Security Council, remembers his reaction to America’s first draft of the resolution condemning Syria. “When I saw it, I knew what were the issues that were put there just to annoy us,” he says, laughing. “And then, at the end of the process, they would just disappear. I’m a professional diplomat. I know this kind of thing. You put in this and that, knowing it’s unacceptable to the other side. And then you drop this and you drop that, and you make it look like a huge concession.”

No one is yet in a position to divine what Bolton’s true motives are. But this much is indisputably true: Bolton is an expert on the organization he distrusts. Even his biggest detractors concede that he knows the United Nations better than any American representative since Thomas Pickering, the legendary ambassador appointed by Bush the elder who was fluent in six languages, including Arabic and Swahili. Recently, I asked the Chilean ambassador, Heraldo Muñoz, whether his colleagues had been nervous before Bolton’s arrival. He let out a hearty laugh. “Oh, no! By no means. It was rather amusing to read the newspaper and see the television.”

Why?

“Because we know how this organization works,” he said. “It doesn’t adapt to a new ambassador. A new ambassador adapts to the organization.”

But to what pickled creation, exactly, is our new ambassador adapting? Step into the U.N., and you’ve slipped not just into another country (or 191 of them) but through a wormhole in space, where it’s 1950 all over again. One still hears plenty of French in the elevators and the halls; people still smoke in the delegates’ lounge; the committees sound as though they were named by Khrushchev. (An actual outgoing voice-mail message: “You’ve reached the office of the special adviser on the follow-up to the report of the high-level panel.”) The Security Council, with its horseshoe-shaped table and clunky plastic headsets, looks like the set of an old spy movie—Dr. Evil addressed a far sleeker room in Austin Powers when he asked for his million dollars—and the palette of the General Assembly is taken directly from an Edward Hopper painting, with plaster chairs of lime green and sky blue. On the floor, the delegates from Iran and Iraq sit next to each other—such is the tyranny of the Roman alphabet—and the ambassadors from Eritrea and Ethiopia are separated only by the gal who represents Estonia. There’s a singularly unresolved quality to the place, as if it can’t decide whether it’s a multicultural Utopia of collective action or a monochromatic dystopia of pencil-pushing futility.

People seldom make jokes about the place, even though the organization by its very nature is the setup to a joke. (A Greek, an Irishman, and an Italian all walk into a room.) Perhaps the funniest observation ever made about it is commonly attributed to Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, the former secretary-general from Peru. Someone asked him how many people worked at the U.N. He thought for a moment, then gave his answer. “About half.”

“I don’t think the U.N., frankly, is taken particularly seriously by anyone very much,” says Australia’s Dauth. “The problem is that there is no global consensus on anything anymore. Much as some people profess to be interested in effective multilateralism, very few countries are—particularly developing countries.”

“He said, ‘So how is the U.N.?’’’ says the Chilean ambassador. “And I said, ‘Well, it’s not as good as it was before you invaded Iraq.’’’

There is an inevitable dysfunctionality, or structural neurosis, to any place that tries to accommodate the desires of 191 nations. Countries that in other multilateral settings would be allies are in this setting nipping at one another’s skirts, because all of them (theoretically) have an equal say. What the developed world wants, the undeveloped world often does not. And no one has a clue what to do with the United States. The U.N. seems to be the one place where the rest of the world can work out its anger toward America; for some countries, humiliating America is de rigueur, a simple matter of course. This impulse is precisely what infuriates conservatives like John Bolton. “In the United States,” explains Jean-Marie Guéhenno, the appealing, highly cerebral undersecretary-general for peacekeeping operations, “there seems to be a perception that the U.N. is not favorable to American interests. But the perception in many countries is that the U.N. is very close to the United States. That is the paradox you see.”

This central tension makes almost every attempt to reform the organization a ludicrous struggle. The developing countries, known as the G-77 (or Group of 77, which in fact is now a group of 132), are convinced, not unreasonably, that the U.N.’s vast bureaucracy—collectively known as “the Secretariat”—is dominated top to bottom by Europeans and Northerners. The Security Council, the only body with any real power, has just five permanent members (the United States, Britain, France, China, and Russia) and ten rotating non-permanent ones. In order to retain what power they have, developing countries insist that most power, especially of the purse, reside with the General Assembly. But the General Assembly tries to operate by consensus, and it’s 191 countries large. One can imagine more efficient ways of conducting business. Like underwater.

The U.N. budget is controlled by something rather ominously called “the Fifth Committee,” whose very name seems to have rolled off the loom of Terry Gilliam’s imagination, or perhaps George Orwell’s, as the preeminent example of something double-plus ungood. I have asked perhaps 50 people whether there are any good Fifth Committee jokes floating around, including how many Fifth Committee members it takes to change a lightbulb. No one could think of any. It turns out the committee more or less counts lightbulbs. This past June, the General Assembly passed a resolution, produced by the Fifth Committee, that prescribed the ratio of printers to desktop computers in peacekeeping missions (one to four).

The secretary-general is powerless to stop this kind of thing. Contrary to public perception, he’s not like a CEO but a chief administrative officer. His powers are few, and every year, because members add more rules, his powers diminish even more. In 2002, Kofi Annan sought to give himself the ability to move at least 10 percent of his employees—970, out of a total of 9,700—according to need, to meet the demands of a tsunami, say, or an earthquake. One year later, the Fifth Committee gave him 50—and this was after the U.N.’s Baghdad headquarters had been bombed. It took sixteen months more to bulk up security at its other posts around the world, because Annan lacked the authority to do it on his own.

It’s hard to imagine another organization with similar mandates—keeping peace, feeding the hungry, overseeing elections—operating under the same constraints. It’s a miracle, given this kind of information, that the U.N. works at all.

And yet the U.N. does work, in some cases quite well. For all its shortcomings, it remains the best hope the developing world has to make its voice heard, and it’s the one organization that can legitimize the use of power by larger nations. The U.N. today feeds 89 million through the World Food Program and has more soldiers on the ground (in eighteen countries) than any army besides the United States’. The Rand Corporation recently came out with a study showing that U.N. peacekeeping troops are far less expensive to maintain than U.S. troops. Last year, the U.N. oversaw elections nearly every two weeks. And it was one of the first organizations on the ground during both the tsunami and the Pakistan earthquake.

To expect the U.N. solely to be a house of reform is, in the end, rather parochial. Its mandate is broad and wide. Reforming the U.N. is hardly what smaller countries care about. They care that the U.N. expand the Security Council and make the council’s meetings more transparent. They want commitments to the Millennium Development Goals, designed to drastically reduce poverty, illiteracy, and the spread of aids by 2015. Certainly, making the United Nations more efficient and accountable would improve the organization—and Annan has just hired Rajat Gupta, a senior partner from McKinsey & Company, to advise him on this subject—but from their perspective it’s hardly the most urgent matter facing the institution.

The irony is, these countries probably would benefit from the reforms Bolton is so crudely pushing. “The biggest problem at the U.N. is not the United States,” says Dauth, “but the G-77, whose tactics are too often screwing the place.”

Baali, Algeria’s ambassador, tells a great story about Richard Holbrooke, Clinton’s U.N. ambassador who hoisted the United States out of its arrears after years of deadbeat neglect. “He knew I had my pride,” says Baali, sitting in his office. He’s imposing and attractive, fluent in Arabic, French, and Spanish. Some find him too slick, but he’s also outspoken and funny, which in this organization counts for something. “He would tell me, ‘Oh, Mr. Baali, you know that you’re the star of Africa,’ ” he continues. “Or, ‘You are the best diplomat.’ This kind of stuff. And I’d say, ‘Okay, Dick. What do you want?’ ”

Each diplomat has his own style. Holbrooke flattered and bullied by turns, which often worked, because he was insanely charming when he wasn’t rude, and he was so cerebral he could get away with it. Bill Richardson, his gregarious predecessor, was more of a sunny politician, glad-handing his way through the halls, smoking cigars and chatting with representatives in the delegates’ lounge. (Until a colleague suggested he stop, he greeted Sir John Weston, the extremely stiff ambassador from Britain, by thumping him on the back and shouting, “Hey, Weston!”)

Bolton’s calling card is directness. For some colleagues, this style works just fine. “People are grateful to you when you put on the table all your cards,” says Baali. “Our discussions have always been to the point and rational,” says a European ambassador. “But if I told this to my local press, they’d question my mental health.”

At the Security Council, Bolton speaks linearly and without notes, but he takes them when others speak, which is the reverse of the usual pattern. He has little patience for procedural rituals; once, in the middle of a long Security Council debate about how best to handle the Iranian president’s call to “wipe Israel off the face of the map,” he grabbed a piece of blank paper in exasperation and drew a map of the region without Israel, exclaiming to colleagues, “This is what we ought to be discussing.” At press stakeouts, he’s proved quite accessible, speaking in colorful hyphenates, garnishing his observations with sarcasm. “Reform is not a one-night stand,” he recently told a group of reporters. Shortly after: “Green-eyeshade, bean-counting business-as-usual is not the solution.” A few days later: “I’d be delighted to address that question … I haven’t given up on the possibility that sweet reason will prevail.”

At receptions, Bolton’s wife, Gretchen, a financial planner, provides a lot of the social grease—she’s sweet-faced, warm, and unafraid of grabbing guests by their arms and leading them into the dining room. He, on the other hand, rises at 4 a.m. to read the foreign press and send out e-mails and in social settings often seems at loose ends. Muñoz, from Chile, tells a story about the first time Bolton paid a visit to his office. “He said very bluntly, ‘So how is the U.N.?’ This is before we even sat down.” Muñoz smiles. “And I said, ‘Well, it’s not as good as it was before you invaded Iraq.’ ”

Bolton can be rude to the help, as advertised. During the negotiations leading up to the World Summit, he repeatedly told members of Annan’s staff, “You have no standing here.” To fellow perm reps, his directness can also come across as crassly undiplomatic. During the summit negotiations, he suggested a compromise on a particular matter to Stafford Neil, the Jamaican ambassador and chairman of the G-77. Neil said he’d have to check with other members of the G-77 first. “Great,” Bolton said, according to someone close to the negotiations. “I’ll throw it into an interagency process in Washington, and we’ll see who gets an answer first.”

“He has a style that is complicated for some colleagues,” says Muñoz. “He tends to lecture. Perhaps he doesn’t fully realize that he’s dealing with individuals who have as much or more diplomatic and political experience as he has—and who have gone through many difficult situations throughout their public life.” He takes a sip of coffee. “Maybe that’s his style,” he continues. “But when one has been in jail, like I have … ” He drifts. “You have to understand that if you’re facing people at the U.N., it’s because they have experience.

“But I’ve been very impressed by him,” he says. “He is extremely well informed. And he has a very dry sense of humor.”

And Bolton has not been rude in the way so many American officials have been rude in the past—namely by requesting meetings with fellow ambassadors, then insisting the ambassadors come to the American mission, rather than going to the representatives’ own turf. Baali remembers being summoned into Madeleine Albright’s office—an office he had loaned her, no less. Albright had graduated from U.N. ambassador to secretary of State by then, but still. “I said, ‘No way,’ ” says Baali. “ ‘She wants to see me? It will be in my office.’ ” He shakes his head. “Bolton,” he declares, “would never do that.”

On a recent morning, Bolton is asked by reporters what he thinks of a New York Times editorial accusing him of “all muscle and no diplomacy.” He smiles. “There are some things that make me happy in my job,” he says. “And that was one of them.”

Whether as a matter of tactics or temperament, Bolton can be stunningly impolitic. In November, he told a group at a New York dinner that U.N. officials lived in a “bubble” and the organization itself is “a target-rich environment.” He also told reporters that Americans, if unimpressed with the U.N., would eventually seek “other institutions, other mechanisms” to resolve their troubles. When later asked about this comment, Kofi Annan offered seven words: “I’m not the interpreter of Ambassador Bolton.”

For a while, Bolton publicly flirted with the notion of the United States’ contributing only to U.N. programs with “à la carte” dues, such as the World Food Program and unicef, because they’re better run—an interesting idea but highly impractical for everyone working on 44th Street, including the secretary-general. “My perception was that his style was more of a prosecuting attorney than a diplomat’s,” says Alexander Watson, Pickering’s deputy ambassador, who dealt with Bolton when he was still an assistant secretary at the State Department. “His interventions were not particularly helpful to achieving our objectives.”

This time around, his colleagues learned this same lesson almost immediately, and quite vividly, in the weeks leading up to this September’s World Summit, a three-day policy rave involving more than 150 heads of state. For months preceding the event, the president of the General Assembly had been trying to write a document leaders could endorse at summit’s end. This prospectus, known as the “Outcome Document,” was supposed to chart the course of the United Nations for decades to come.

Then Bolton arrived. Almost immediately, he sent out a letter to his colleagues saying he harbored reservations about the document—roughly 700 of them. Among them were all references to the Millennium Development Goals. “Even the secretary-general reacted,” recalls Baali, from Algeria. “The Millennium Development Goals are like the Holy Koran.”

It’s entirely possible—likely, even—that if Bolton hadn’t done so, others would have intervened to rewrite the Outcome Document, too, and the United States had made known various objections to the document from the beginning. But as soon as Bolton forced the issue, it was a free-for-all. Libya, Cuba, Iran, Pakistan, Egypt—all of them declared open season on the document, because they objected to its tougher stances on human-rights violations and nuclear proliferation. And Bolton was perfectly content to work with them. “Right from the start,” says Stedman, one of the architects of the document, “Bolton was intent on dealing only with the spoilers.”

By summit’s end, the Secretariat itself had to intervene to produce the compromise Outcome Document, maneuvering around Bolton and instead going directly to Condoleezza Rice and British foreign secretary Jack Straw. The Millennium Development Goals stayed. But the document contained neither a definition of terrorism nor a statement about nuclear proliferation and disarmament, arguably the most urgent concerns of the United States. (Annan called the latter omission “a disgrace.”) Its language about the Human Rights Council, meant to replace the Commission on Human Rights with something that actually worked, got watered down to a few paragraphs. On a December day, I visit Munir Akram, the ambassador from Pakistan. He has a reputation for being smart and as unyielding as leather, formidable both for his eloquence and the feline softness with which he speaks. I want to know whether it was useful to have the United States in his corner during the World Summit.

“It is always useful to have the United States in your corner,” he says, chuckling. His thick hair is pomaded back in such a way that implies a ponytail at the end of his head, though there is none. He lights a brown cigarette—a Cuban Cohiba.

I ask if this is the only remaining building in New York where one can have a cigarette at one’s desk.

He drags deeply. “Actually,” he says, releasing a long stream of smoke, “it’s illegal.”

“Every country in the world, in a way, defines itself a bit vis-à-vis the United States, so it’s a difficult job to be its ambassador,” says Guéhenno, the undersecretary-general for peacekeeping operations, sitting in his corner office on the 38th floor. “It’s easier to be an ambassador to a small country,” he says, “because not everyone pays attention to your words, moods, and statements.”

Though the United States is hardly popular in the corridors of the U.N. right now, this is hardly the country’s nadir. During the mid-nineties, when we were deep in arrears, animosities toward the United States were just as acute, perhaps even more so. Complicating matters, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the Egyptian secretary-general, had no great love for the U.S. and even less love for our ambassador, Madeleine Albright, whose criticisms he once deemed “vulgar.” The Bush administration has kicked in more money for peacekeeping than Clinton did, mostly because the president has been able to convince the Republican Congress, in a way that Clinton never could, that it’s a good idea. Condoleezza Rice and Stephen Hadley, Bush’s national-security adviser, speak regularly with various people in the Secretariat. And if the U.S. were held in such low esteem, an American judge would not have been reappointed to the International Court of Justice in November.

The truth is, ambassadors come and go. Governments reconstitute themselves; new presidents are elected. “There isn’t one American foreign policy,” says a European ambassador. “Bolton represents one part of the United States. One has to be blind not to see this country contains multitudes.”

Yet in the U.N. at the moment, Bolton is the emblem of American exceptionalism, an attitude that much of the world sees as the problem. He’s delighted to play the role of the Ugly American. And maybe that’s not such a bad thing for the world to see—at least it knows what it’s getting.

For now, the one reform at the U.N. Bolton can be sure of is of the building itself, which is badly in need of repair. The latest renovation plans call for refurbishing it ten floors at a time. When he heard about it, the first thing he did was tell colleagues it wasn’t his idea—and he was happy to see the ten floors at the top restored, just like every floor below.