The Cardinal came to bless the computers. One million dollars’ worth of new PCs and dataports in the renovated library of the College of New Rochelle. After accepting an honorary degree and two standing ovations from students and faculty, Cardinal Edward Egan smiles and waves his hands over the Dells, those gleaming, blinking agents and symbols of modernity, openness, and the free flow of ideas.

Then the archbishop of New York flees the information age, sneaking out the library’s back door.

The New Rochelle campus is not a large place, however. All exits are being watched. Now a dozen minicams and fifteen reporters stampede toward Egan.

“Cardinal, what about the pedophile priests?”

“Archbishop Egan, have you heard from the district attorney?”

“Who are the six priests you suspended?”

“Do you have anything to say to the victims?”

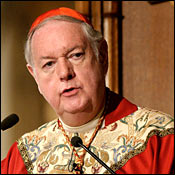

Imposing at six foot two and well over 200 pounds, regal in black cassock and red skullcap, Egan never breaks stride. The scrum of reporters backpedals, trips, tangles. Egan never makes eye contact. He remains as serene as the lush green spring grass. His only words are to his beleaguered spokesman, Joseph Zwilling. “Which way are we going?” he says in a low rumble, having momentarily lost sight of his waiting black limo, the one sitting curbside with the engine running. Zwilling points. Egan picks up speed.

The rear door of the limo opens. The media pack closes in. Egan bends, sits, the door slams shut. The limo races away, déjà vu rising in its exhaust. This scene has been played many times before, but it lacks one detail: A cop’s hand on the top of Egan’s head, that oddly gentle gesture of concern for a perp’s skull as the accused is folded into a squad car.

When it comes to coddling perverts, the record of Boston’s Cardinal Bernard Law is far worse. But somehow, Cardinal Egan acts guiltier.

As the headlines about sexual abuse and Roman Catholic priests have grown more revolting and frequent, Egan, one of the American church’s most influential figures, presiding in the nation’s media capital, has grown ever more remote. “I have no question about his deep faith and piety and devotion,” says a frustrated New York cleric who is friendly with Egan. “But I really don’t understand what he is doing. He lacks a pastoral sense – the touch of understanding what goes to the heart of faith and of the mystery of the sacraments and of the church and of the Gospel. He acts as if he had something to hide – or that he’s just above it all.”

The dismay over Egan isn’t just quibbling about style. “He’s got a tough job, and I want to help him,” an anguished Upper West Side priest says. “I just wish he’d make it easier to help him.”

And Egan, in one sense, is also a victim: of the Vatican’s flawed promotion process. The city’s Catholic flock has been whipsawed between John O’Connor, who was charismatic but who nearly bankrupted the archdiocese, and Egan, a wizard of finance in a moment crying out for prodigious empathy. Parishioners see the archbishop of New York as a public leader, but Pope John Paul II has different priorities when selecting key lieutenants. “This pope rewards loyalty much more than competence or creativity,” a veteran city priest says.

The nuances of power inside the Beltway are simple compared with those inside the Tiber, and Egan has long been a master of the Vatican’s arcane politics. Openness and empathy are not what propelled Egan to the highest honor of his career. It was a skill for climbing bureaucratic heights that earned him the nickname Alpine Ed.

The cardinal enjoys using his substantial power over the lives of New York priests, dictating everything from budgets to altar design. “In private, he comes across like a gangster,” says a New York cleric who has known Egan long and well. “But our gangster, on the right side.” This senior official admires Egan but nonetheless keeps a cautious distance. “He’s tough, very tough, very caustic in his judgments of things that he thinks are being done wrong. Very candid about who’s up, who’s down, who’s screwing up. He’s a political, streetwise operator – not for nothing he’s a Chicago kid.”

From the outside, it may look as if Egan is engaged in a Nixonian coverup. But the cardinal is ever focused on the inside game: His actions are apparently driven by his astute readings of the Vatican politburo. At the highest levels of the church, the sexual-abuse scandal is also the latest skirmish in a long-running power struggle between the American bishops’ conference and the Vatican. The conference leadership pushed for a “one strike and you’re out” sexual-abuse standard during the recent Vatican summit. The pope and his inner circle demurred – leaving power in the hands of the Vatican and individual bishops, even if it was terrible P.R.

Egan is solidly in the Roman camp, and the relations he cares about aren’t remotely public. His defensive strategy has played far better in the Vatican, a place to which Egan would happily return. “He’s been a hierarchical apparatchik all his life,” says a priest familiar with Egan’s life and thinking. “Don’t get me wrong – I think he’s a very devout believer, a prayerful man, a man of great personal integrity. But he’s very ambitious, and has a very clear trajectory in mind as to what God and the church want him to do. He has an astonishing confidence in his own judgment. That undoubtedly has everything to do with why he has such a narrow circle of consultation – or none at all.”

And he isn’t about to change now, at the age of 70. “Ed,” says Father Dick Ehrens, a pal of Egan’s since they were teenage freshman seminarians, “is indomitable.”

Oak Park, Illinois, is famous as the birthplace of Ernest Hemingway. It is Edward Egan’s hometown as well. The Oak Park of Egan’s childhood, in the thirties and forties, was an upper-middle-class Chicago suburb, with masterpiece Frank Lloyd Wright–designed houses and leafy, shaded streets. “The cardinal is lace-curtain Irish,” an Egan supporter says. “Not like me – shanty Irish.”

Egan was the third of four children, and the second son. Polio struck him down as a 10-year-old. “Father Tim Lyne was then a young priest at St. John’s in Oak Park, and he would take Eddie Communion in the mornings, at Ed’s home,” Ehrens says. “For a kid to be getting Holy Communion like that was kind of special.” Those priestly house calls were the first in Egan’s string of attachments to powerful patrons: Lyne became the second-highest-ranking bishop in Chicago.

Egan’s father was a successful salesman, his mother a teacher, and he was close to an uncle who was a doctor. “Ed’s father would have been happier if Ed had gone into business,” Ehrens says. “But Ed had his calling.”

Ehrens remembers visiting the Egan house on weekends and vacations. “At the end of dinner, we’d all gather around the piano and we’d sing everything,” he says. “Ed could play anything, from the classics to the modern stuff. His mom would sing as loud as the rest of us. The dad, though, he’d slip upstairs. Ed has got the drive his father had, but he’s got the softness his mom had.”

First in his class every semester, student-body president, Egan was a star seminarian, and at 21, he was selected for polishing in Rome. Egan fell in love with Vatican politics and the ancient city itself. Though he has served in important American roles – first as an apprentice to Chicago cardinals Albert Meyer and John Cody (“Ed knew all the people in power in Chicago, how to deal with them; he knew their tactics,” Ehrens says), then as bishop of Bridgeport – Egan has always seemed most at home in Italy. Egan’s only brief experience as a common priest was in 1958 – and not in some scruffy neighborhood parish but at Chicago’s Holy Name Cathedral. A short teaching stint, a judgeship on the Vatican’s highest court, and a series of weighty executive jobs mean Egan has spent most of his 45 years as a priest behind desks.

Egan has a graduate degree in canon law, and in the early eighties, it landed him a coveted position redrafting the code of canon law. Part of the job entailed sitting with the pope each morning at breakfast, explaining the changes. Father Roger Caplis remembers Egan visiting from Rome once during those days. Caplis, a seminary pal of Egan’s, invited his illustrious friend to appear on a Catholic TV show he hosted in Chicago. “Ed had always been one of the more articulate guys, and on the show he was searching for a word – this is unbelievable for Ed,” Caplis says. “Afterward, I said, ‘Eddie, what happened?’ He said, ‘You know, I think in Latin.’ “

John O’Connor’s smarts were honed in far different places: his blue-collar family home in West Philadelphia and the U.S. Navy. In 1985, the pope dispatched Egan to work for Cardinal O’Connor in New York, as vicar for education. The friction started before Egan even unpacked. O’Connor needled the new man by saying Egan had requested an apartment spacious enough to accommodate his grand piano. “He has indicated that he’ll be needing very large quarters, and I have found them,” O’Connor said. “Across the river, in Newark.”

In 1988, Egan gladly accepted appointment as bishop of Bridgeport. Then he got a look at the diocese’s multi-million-dollar debt.

The fiscal mess enabled him to build a reputation as a management genius. He demonstrated a gift for reeling in donors, many of them top corporate executives: Louis Gerstner, IBM’s boss; Lawrence Bossidy, the head of Allied Signal; and NBC’s Bob Wright. GE’s Jack Welch became such a cherished friend that Egan acted as a personal Roman tour guide for Welch’s then happily married second wife, Jane. A 1993 Egan fund-raising campaign with a goal of $30 million raked in $45 million. Egan also revamped the recruitment of potential priests and dramatically increased vocations in Bridgeport.

Considering Egan’s public aloofness and brutal managerial hand, it is startling to hear the private man repeatedly described as engaging, entertaining, and witty. “He’s a very affable, very friendly man,” says a New York bishop who is nonetheless afraid to be quoted by name. “He’s extraordinary in his kindness toward the people who work in the residence, people who cook for us and clean and look after us.”

“When you meet him, he’s thoughtful, he’s got a great sense of humor, he’s extremely well versed in music,” says Peter Flanigan, the UBS Warburg adviser who helped launch New York’s Student Sponsor Partners, which places students in Catholic schools and pairs them with tuition donors, adding 1,600 kids and $6 million to the church-school roster annually. Flanigan has been friendly with Egan since 1987. “He has gravitas and force, but he’s in no way stiff,” Flanigan says. “He had an opera gala night in Bridgeport, to which a lot of people from the Met would come and perform. I’ve been to the opera with him; we went to Fidelio, and I remember saying, ‘This is my favorite opera.’ And he said, ‘Mine too.’ “

Richard Gilder, the conservative Wall Street financier, has chewed over education policy with Egan. “He’s much warmer than O’Connor, and I think less of a bullshitter,” Gilder says. “I always thought O’Connor was sort of a little bit of a blowhard. This guy isn’t. He’s much more of a man’s man.” Gilder pauses. “I shouldn’t say that in this connection. He’s just a good guy.”

Egan inherited a second ugly problem from his predecessor as bishop of Bridgeport. Lawsuits alleging sexual abuse by diocesan priests began cropping up in the early nineties. At first, Egan spared the church substantial embarrassment and costly settlements. His strategy was simple.

“Egan dug his heels in. He refused to budge,” says Raymond B. Rubens, the lawyer for the Reverend Raymond Pcolka, former pastor of Sacred Heart Parish in Greenwich. More than a dozen people, men and women, had accused Pcolka of molesting them in various parishes from 1966 to 1982. “I recall talking with attorneys for the other defendants, who’d been hired by the diocese, and telling them they were nuts – the diocese had to settle these cases,” Rubens says. “I said, ‘If there’s any truth to this, it’ll damage the church.’ And they told me, point-blank, as long as Egan was there, there wasn’t going to be any settlement. Obviously, Egan wanted to become a cardinal.”

But a 1997 case finally forced Egan to publicly confront the issue. The Reverend Laurence Brett was accused of sexually abusing Frank Martinelli, a student at Stamford Catholic High School, in the early sixties. Brett had been sent to New Mexico for psychiatric counseling after admitting he bit a boy’s penis to prevent him from ejaculating during oral sex, then continued to work under the supervision of the Bridgeport diocese until the early nineties, well into Egan’s term.

In 1997, Martinelli sued the Bridgeport diocese for damages. Egan claimed he was scheduled to be in Rome and couldn’t show up in court, but he agreed to testify on videotape. In his answers, Egan debates semantics and expresses no sympathy for the victim. He argues that priests are “self-employed” because they draw salaries from individual parishes.

William Laviano, the plaintiffs’ lawyer, asks Egan about a diocese memo distributed while Brett was away for treatment. The memo says, “A recurrence of hepatitis was to be feigned should anyone ask” about Brett’s absence. “Is it your understanding of this reference that if anybody asked why Brett was gone, somebody should lie and say he had hepatitis, right?” Laviano says on the video.

“If you want to interpret it that way,” Egan replies, “but that is not what it says.” Laviano asks Egan about the meaning of the word feign. Egan tries to play it off to sloppy writing: “What you have here is a young priest, who was vice-chancellor, using a word with a certain flair.” Egan’s combative testimony in the Brett case drew little attention beyond Connecticut; Martinelli and the diocese agreed to a settlement in April 2000.

That same month, the pope was preparing to send Egan to rescue another diocese with massive debts: New York. In choosing Egan, the pope overruled a Vatican nominating committee – and disregarded the wishes of Cardinal O’Connor, who’d made one last trip to Rome to lobby against Egan as his successor before succumbing to a brain tumor in May 2000. Egan’s selection as the new archbishop of New York set off a flurry of action in Bridgeport as well. “Once Egan left,” says Rubens, the Connecticut defense lawyer, “the settlements took place in jig time.” The diocese, admitting there had been “incidents of sexual abuse,” paid roughly $12 million to settle 26 cases against five priests.

Egan had already moved on without major damage to his personal reputation, though, and now he had far bigger numbers to worry about in New York.

By the end of O’Connor’s sixteen-year tenure, the archdiocese of New York was bleeding $20 million annually. Egan slashed civilian staffing inside 1011 First Avenue, the archdiocese headquarters. He tabled most construction projects. Egan also saved money and sent a message by shrinking Catholic New York – the weekly archdiocese newspaper became a monthly. Under O’Connor, CNY was a closely watched political organ. “Egan doesn’t write,” says a senior New York priest who considers the cardinal a friend. “O’Connor was an incessant writer and communicator. And Egan is an overachiever on a number of scores, but on no score so much as demonstrating that he is not John O’Connor.”

Parish priests complain that Egan has kept them in the dark on issues large and small, switching their health-insurance carrier and replacing the leadership of St. Joseph’s Seminary without warning. “He came in and said, ‘If your name is not on this list, you’re not working here anymore,’ ” one priest says.

Egan raised the goal of the yearly Cardinal’s Appeal, a spring fund-raising drive, by as much as 150 percent in some parishes and brought in Community Counselling Services, the corporate consultant he’d used in Connecticut, to run it, inducing widespread grousing. The Appeal has raised just $8.2 million toward its goal of $15 million, so its deadline has been extended until the end of June.

As a pastor, Egan also draws mixed reviews. He is keeping to his promise to preach two Sundays a month in churches other than St. Patrick’s until he visits all 413 parishes in the archdiocese, which includes Westchester, the Bronx, Manhattan, and Staten Island. When the World Trade Center was attacked, Egan’s initial response was a healing one: He went to St. Vincent’s Hospital, expecting to help comfort survivors.

Still, Egan’s whereabouts in the days after September 11 became a source of controversy. In early October, he stuck to his schedule and flew to Rome to preside over a monthlong bishops’ synod. Egan conducted a special, poignant Mass for rescue workers at St. Patrick’s, but his low profile led to the myth that Egan had high-tailed it to Italy on September 12 and refused to return.

“That was a real bum rap,” says a priest who is generally no fan of Egan’s. “But the reason he got accused this way was that he was so damn invisible in the media. He was here, but he wasn’t doing things publicly the way the cardinal archbishop of New York should. He has no appreciation for his symbolic leadership role.”

For all the bumps, though, after two years in charge, Egan was well on his way to another victory. His touch with the elites remains deft. In March, Howard Rubenstein, the public-relations man who is one of the city’s savviest power brokers, hosted a dinner for 35 at his East Side home with Egan as the guest of honor.

“He’s made a really good impression on a lot of people,” says Rubenstein, who is on the board of directors of the church-affiliated Inner-City Scholarship Fund. “He pays attention when you’re talking to him; he really focuses on you. We were talking about Israel, the heritage that Catholicism grew from, and he was able to quote from the Old Testament and the New. He amazes me in his knowledge, of Judaism as well as Catholicism. He’s got a great sense of humor. He talks about Chicago politics with a real glint in his eye.”

Egan is on target to cut the $20 million archdiocese deficit in half by September, and eliminate it completely in the next fiscal year. When he came to New York, analysts predicted a wave of Catholic school closings; so far Egan has kept open all but three. So it must gall him that the magic he’s performed with New York’s financial morass, the whole reason he came here, is quickly being buried by the clamor about old sexual misdeeds.

At first, Boston’s Cardinal Law was the scandal’s leading villain. Then, in March, the Hartford Courant published sealed transcripts of Egan’s depositions in a 1999 pretrial hearing. Suddenly the behavior of Raymond Pcolka came back to haunt Egan. A dozen former altar boys and parishioners had accused the former priest of heinous acts. “Let us please remember,” Egan said, according to the Courant, “that the twelve have never been proved to be telling the truth.”

Cindy Robinson, the plaintiff’s lawyer, asked Egan if he was aware that the cases against Pcolka involved oral sex, sodomy, and beatings. “I am not aware of any of those things,” Egan said. “I am aware of the claims of those things, the allegations of those things.”

Robinson parried: “And you are clearly aware of the number of people that are making these similar claims during the same period of time, over a long period of time, involving Father Pcolka, correct?”

“I am aware,” Egan said, “that there are a number of people who know one another, some are related to one another, have the same lawyers and so forth, I am aware of the circumstances, yes.”

Later, according to the transcripts published in the Courant, Robinson questioned Egan about his stewardship of another accused priest, Laurence Brett: “He admits apparently that he had oral sex with this young boy and that he actually bit his penis and advised the boy to go to confession elsewhere?”

“Well, I think you’re not exactly right,” Egan replied. “It seemed to me that the gentleman in question was an 18-year-old student at Sacred Heart University.”

“Are you aware of the fact,” Robinson countered, “that in December of 1964 that an individual under 21 years of age was a minor in the state of Connecticut?”

“My problem, my clarification, had to do with the expression ‘a young boy’ about an 18-year-old,” Egan said.

“A young – all right, a minor, is that better, then?” Robinson said.

“Fine,” Egan answered.

Egan is a skilled lawyer, so his narrow responses under hostile questioning were appropriate. More damaging is an Egan memo from 1990, regarding a meeting with the egregious Brett. “All things considered, he made a good impression,” Egan wrote in his notes as quoted in the Courant. “In the course of our conversation, the particulars of his case came out in detail and grace.”

Robinson isn’t objective; she was trying to win money for her client. But her impression of Egan’s performance in Bridgeport squares with other people’s memories. “What’s absent in Cardinal Egan and what’s so disturbing is any sense of pastoral concern for victims who are all part of the Catholic faithful,” Robinson says now. “He operates like a businessman. The striking thing with Egan during the whole course of the litigation was that he refused to comment on it. The first words I recall Egan saying publicly that indicated any sympathy or support or concern was most recently, when he’s been under attack and issued a statement through his office in New York.”

Some expected Egan to adopt a more sophisticated public approach when the current crisis broke. “This thing blew up in Boston, but we knew it was going to come to New York,” a city priest says. “The archdiocese should have gotten ahead of the story. Isn’t that what you always want to do? As soon as questions were raised here, they could have said, ‘Look, we’ve already gotten all of our files and we’ve referred anything of interest to the district attorney; we’ve already done that.’ That would have taken the steam out of the story. But there’s something in the Catholic culture about ‘We don’t deal with the media.’ It’s paranoid. And good priests are taking a beating because Egan doesn’t give us any support.”

On Palm Sunday, from the St. Patrick’s pulpit, Egan made his most extensive remarks on the scandal, vowing to prevent future abuse. His main comments have come in four written statements notable for their chilly, legalistic tone and for Egan’s claim that he’s relied on the evaluation of psychiatrists to determine which accused priests were fit to return to work. Egan’s first and longest document came with a gag order: Pastors should not sermonize on the very subject that was foremost in parishioners’ minds. “Why is the bishop trying to muzzle me from speaking about something that is so urgent to our people?” asks an outraged Manhattan priest. “It shows no faith in us. And why couldn’t the letter have had some empathy in it? I mean, Con Edison could have written a warmer letter! Their statements don’t say, ‘Gee, our attorneys won’t let us say we’re really sorry that your gas is off.’ “

In early April, as complaints about his intransigence escalated, Egan forwarded old sexual-abuse allegations to the Manhattan district attorney. Later, he announced he would suspend any priests accused of misconduct. Yet even Egan’s friends are saddened and astonished by his clumsiness in managing the scandal. “He wants to tamp it down, but you can’t do it this way,” a longtime associate says. “You subdue the frenzy by dealing with the frenzy up front. It’s painful to see him go through this. My guess is he’s talking to Rome and getting his advice from there.”

Inside Egan’s bunker, they’re indignant about all the criticism. “He’s communicated directly with the parishes in letters that have been sent out; it’s a matter of public record,” seethes a crusty monsignor. “What the papers are sore about is that he doesn’t deal directly with them. That’s the way he’s selected to do it, because they’ve misquoted him and put wrong stories in. Why should he be bothered acceding to any request they’re making?”

Egan is right to be skeptical of the media. But not all his communication problems are the fault of microphones and newsprint.

One week after returning from the sexual-abuse summit in Rome, Egan invited his diocesan priests to Yonkers. Five hundred showed up, willing to listen, but many with clear memories of the first time Egan had asked them all to St. Joseph’s Seminary for a chat.

It was July 2000, a month after Egan’s arrival in New York, and the occasion was an informal get-to-know-you barbecue. “It was an attempt to reach out, and that was good,” one priest says. “He was gregarious.” In smaller social settings, Egan drops the lugubrious baritone that he uses from the pulpit, the medieval tone that makes him sound as if he were playing a priest in a Vincent Price movie. Yet even out on the seminary lawn, Egan wasn’t completely at ease. “He wore a green sports shirt,” a Manhattan priest says, “but he didn’t allow anyone to take a picture of him in it.”

Inside the St. Joseph’s Seminary gym on the morning of April 29, priests gathered around small tables and listened anxiously to the archbishop. They were reassured by hearing a somber Egan express sincere sorrow for the abused children. They were curious about his plan to raise money for a legal defense fund that would be strictly separate from archdiocese accounts. They weren’t surprised when Egan complained about the media harassing him – only that he took evident delight in keeping the press guessing as to the exact number of New York priests who’ve been suspended.

Far more disturbing was Egan’s proportioning of victimhood. “He thinks the innocent priests and the church are the martyrs in this, not the kids,” one appalled priest says. “He still just doesn’t get what people are angry about.”

Perhaps for once, Cardinal Edward Egan could direct his gaze down the church ladder instead of up. He’d see the only true Christian charity to emerge from this tawdry saga. In a cramped midtown rectory, a priest puts down the morning’s tabloids, their headlines announcing the summary dismissal of six unidentified Catholic pastors. The priest’s hands are shaking. He has no sexual-abuse worries of his own, but he’s rattled both by the evil in the church ranks and by his leadership’s cold-blooded response to the crisis.

“Every priest swears an allegiance to the archbishop of New York,” the priest says quietly. “Do I like him? I don’t know. But I am called to love him.”