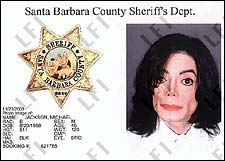

I’m looking at Michael Jackson’s Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Department mug shot, and I’m thinking it’s no longer technically a human face (it’s Lily Tomlin melting, or Lily Tomlin as reconstructed by a mortuary makeup artist). It’s now, chiefly, a metaphor. It represents, of course, self-transformation gone horribly awry, and self-hatred, and self-destruction.

But it also represents a collective fear: that it’s not bad parenting, stolen childhood, or music-industry insanity that’s to blame for Michael’s ongoing meltdown. Celebrity culture has done this to him. And, so, by extension, have we.

He’s our Michael, our icon—a (formerly) gifted artist—and we let him do this to himself. He’s our American tragedy.

Michael Jackson’s nose is just the crumbling tip of the iceberg.

The corroded 45-year-old man we see today is arguably just a logical outcome, an extreme outcome, of an off-the-charts case of celebrity-entitlement psychosis. The former King of Pop now seems to be, somehow, the perverse product of the limitless love he enjoyed from fans in his prime. He doesn’t know he’s been deposed; he lives in (clueless) exile in a hermetically sealed world tailored to his own tortured specifications. He’s reimagined Neverland, his gated little patch of Santa Barbarian paradise, as not just his personal Disneyland but his private ancient Greece. Carnival rides plus man-boy sleepovers.

But as astonishingly reckless and delusional as Michael is (my God, love letters to a 12-year-old boy!), he’s somehow still part of a celebrity continuum. He’s an Über-freak, but of a type. Consider, for starters, his friends/former friends: Elizabeth Taylor and Liza Minnelli (and David Gest!).

And then consider the other conspicuously narcissistic celebrities (besides Liza and David) who have also suffered showstopping meltdowns lately: Paris Hilton and Martha Stewart and Rosie O’Donnell and Kobe Bryant and Rush Limbaugh. All of them caught in acts that betray their entitlement, their grandiosity, their neediness, their emotional greed, their expectations of blanket (or at least red-carpet-like) immunity. The world—with its petty little rules and restrictions and proprieties—is doing them a grave injustice.

Michael Jackson’s face is celebrity culture’s death mask.

Okay, yeah, we’re more celebrity-obsessed than we’ve ever been. But the ground, in that regard, has shifted rather radically beneath our (and their) feet: Our relationship to celebrity—and celebrity’s relationship to itself—has been so transformed over the past few years that these days it doesn’t take much to crack the veneer of celebrity news (even seemingly positive celebrity news) to decode what celebrity now means to us as a culture.

Almost entirely gone is the presumption that we’re interested in celebrities because of their talent or their work or because they’re leading exemplary lives or because they’re the first among equals in our supposedly egalitarian society, with America’s celebrity-watching being some sort of less inbred version of Britain’s royal-watching.

Rather, in the same way that, on the 40th anniversary of JFK’s death, it’s easy to observe that glamour has largely been drained from post-Camelot politics, we all regard celebrity glamour as a deeply suspect, ephemeral commodity. (Of course, the most salient feature of the JFK-anniversary TV orgy has been all the attention paid to the revelations about his medical ailments and sexual adventures. JFK’s image, in this revisionist moment, is now perceived to have been as engineered as, say, FDR’s.)

As celebrity has exploded, it’s also simultaneously been reduced (the Us Weekly effect) and pathologized (the “Page Six” effect) and deconstructed (the Behind the Music effect) and cheapened (the reality-TV effect). It carries with it a whole new set of signifiers and layers of meaning.

Not that all consumers of celebrity culture, and players in the celebrity-industrial complex, seem to grasp this.

When, earlier this year, Rolling Stone owner-editor Jann Wenner sat in Charlie Rose’s blacked-out studio and Charlie asked him why magazines are so celebrity-mad right now, Jann had a simple answer: “It’s uplifting to read about.”

Honestly, when I heard that, I practically did a spit take. In fact, I hit the instant-replay button on my TiVo to make sure he really said that (he did!). Then I thought, What planet is Jann living on?

Okay, on Planet Pop, where Jann owns several homes, I guess you could argue that stars are still gods. Bad behavior among rock and pop stars, of course, has traditionally burnished, not damaged, reputations. (Witness the unsettling sight of still-starstruck, supportive fans swarming Michael Jackson’s SUV after his arrest.) In fact, Jann is not only one of the original celebrity-editors (along with Hugh Hefner), he’s the Ur-fanboy-journalist, having created his magazine back in 1967 in large part to get close to the objects of his adoration. Jann and his team of golden-moment photographers (Annie Leibovitz and others) created one of the classic formulas for the deification of rock stars—a formula Tina Brown and Graydon Carter later adapted and turbocharged for Hollywood at Vanity Fair (where Leibovitz now works).

But the celebrity-industrial complex isn’t, duh, about uplift anymore. Just ask Paris Hilton, whose sex-tape scandal—suspiciously timed to coincide with the premiere of her new Fox reality series—is hardly scandalous. In fact, the only achievement her celebrity has ever reflected is that she’s a constantly-falling-out-of-her-clothes exhibitionist. A celebration of vapidness as a form of postmodern brand purity, Paris is a beautiful rich girl unencumbered by any agenda beyond ubiquity. Her sex tape merely reinforces her image: She falls all the way out of her clothes! And a video camera happens to be there! It was only a matter of time.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in Celebrityville, Queen of Nice Rosie O’Donnell, friend of chubby housewives everywhere, reveals herself to be a complete fraud—she’s not only not nice, she’s a dyke and a bitch—and proceeds to drive her eponymous magazine into the ground while berating a cancer-victim employee.

Michael on the Couch

By Daphne Merkin

Michael Jackson wanted to lookdifferent, to be different, to go back to his unhappy childhood and relive it and try to make things better. The differencebetween him and ordinary neurotics is that he could.

Homemaking goddess Martha Stewart takes an ungodly interest in the disposition of one foundering little chunk of stock among her vast holdings—as if selling on insider information, and lying about it, as the Feds maintain she did, is just as proper and artful as applying toile and acorns to a picture frame with a hot-glue gun.

Goody-goody Lakers guard Kobe Bryant allegedly turns into an arrogant kiss-my-prick sexual predator (or at least a clueless pickup artist who can’t fathom that not every woman wants to fuck him—his way).

Sadistic right-wing radio blabbermouth Rush Limbaugh is struck suddenly silent when the news gets out that he’s addicted to white-trash heroin OxyContin, which, it turns out, he used the help—his maid/dealer!—to secure for him.

Robert Blake molders in Hollywood, muttering slurs about his murdered wife, hoping Baretta will save the day.

And good old M.J.: It’s déjà vu all over again, because, remember, he bought his way out of boy-trouble almost exactly ten years ago. (At least, so far, there doesn’t appear to be video documenting his love life. His colleague R. Kelly—Michael was filming his new music video with R. in Sin City when the sheriff put out the warrant for his arrest—isn’t so lucky. His alleged trysts with a 14-year-old girl, documented by a camcorder, are sure to air in court.)

There’s a compulsiveness that these stars exhibit, making mistakes, sometimes over and over again, that are entirely in character—effectively branding their misbehavior.

We’re supposed to pretend to be shocked?

Of course, part of the reason the Church of Celebrity stopped beatifying saints—there will never be another Audrey Hepburn or Jimmy Stewart—is because it gave away every last one of its mythmaking secrets. There are no more certified miracles in Hollywood.

Anti-glamour, or deconstructed glamour—or pure roguishness—sells now partly because mere glamour (already in oversupply) doesn’t really sell on its own anymore. It almost always comes with myth-busting backstory.

As recently as the early nineties, the mechanics of glamour were largely opaque to the culture at large. Celebrity stylists and colorists and personal trainers and plastic surgeons were not celebrities themselves. InStyle—and before InStyle, the Condé Nast beauty magazine Allure—were just beginning to advance the do-it-yourself, do-try-this-at-home approach to celebrity glamour.

But since then, so many celebrities have let themselves unwittingly become walking infomercials—allowing the narrative that surrounds them to be about not only their “beauty secrets” but their conspicuous consumption and luxury-product choices—that celebrity, the word itself, has taken on its own stand-alone brand value. Drugstores stock the Hollywood Celebrity Diet and Celebrity White tooth bleach, and we understand implicitly what’s being sold. Celebrity isn’t about talent, it’s about getting what you want—now.

The InStyle mentality, spread through-out celebrity culture, leaves the net impression that even the seemingly natural Hollywood beauty is actually a confection, a collage. To be in InStyle (or its many imitators), you must confess (without, it seems, even really apprehending that you’re confessing) that you’re the sum total of your hair and makeup and wardrobe. You are your image—what the image-makers on your payroll dreamed up. You are, in a word, a construct.

A construct that can come apart at the seams at any moment the media decide to part the curtain, it turns out. All the celebrity weeklies have done scalpel-happy cover stories this year—the most recent being Us Weekly clone In Touch Weekly’s plastic surgery secrets package (MEG RYAN: BATTLING RUMORS ABOUT HER LIPS; PAMELA ANDERSON: REGRETS BREAST IMPLANTS?).

And just in time for Thanksgiving (though, really, it felt like an early Christmas gift), Star magazine’s STARS WITHOUT MAKEUP! COVER. A smaller headline reads LOTS MORE SHOCKING PHOTOS INSIDE!, but the photos, at this point, aren’t all that shocking (Britney Spears is a little ragged, Cameron Diaz is plain, Renée Zellweger is blotchy, and Barbra Streisand is a hag).

Which doesn’t make them any less irresistible, or at least salable. The makeup-less cover is already one of Star’s best-selling covers of the year—the tabloid’s editor, Bonnie Fuller, is reportedly set to get a $10,000 bonus for hitting a new circulation high with it.

Bonnie, of course, is the celebrity editor who is most widely credited with masterminding the new celebrity “journalism” paradigm. Her current reign was enabled by Jann Wenner, who, in an inspired moment in early 2002, hired her to run Us Weekly. Never a corporate loyalist, she quit Us this past summer to run the Star and American Media’s other tabloids for $3 mil a year.

The net effect of her tenure so far has been to reinforce the idea that not only is your average celebrity “just like us” (to use Bonnie’s signature Us Weekly–era phrase), but that he or she is badly in need of an intervention. Of Britney Spears, a “source” (probably the mailroom guy at the Star) observes, “She looks very tired.” The solution suggested: L’Oréal Touch-On Colour, Shimmering Bronze (just $8.99 at Walgreens). “Apply it,” a makeup artist helpfully explains in the magazine, “on the forehead, nose, cheeks, and chin.”

For the moment, the most perfectly realized form of celebrity—an old-school, untainted, high-glamour type of celebrity that allows the media, once again, to engage in undiluted hagiography—is the reality-TV celebrity. Us Weekly gives “Bachelor Bob,” of ABC’s The Bachelor, a cover and asks WHOSE HEART WILL HE BREAK? He’s holding a red rose.

Johnny Depp, this year’s “Sexiest Man Alive,” is half-crowded off the cover of People by Bachelor Bob and his chosen mate, Estella. “We want to make it last,” Estella coos in a big headline.

In Touch declares Trista and Ryan, of The Bachelorette, 2003’s “Most Romantic Couple.” (Jennifer Aniston, of Brad & Jen fame, is merely “Most Talked About.”) ABC is giving the reality-TV couple’s marriage—the culmination of their “televised true love story” from last season—royal-wedding treatment in a prime-time ceremony.

And just before Thanksgiving, Fox aired the American Idol Christmas special—starring Clay Aiken, Ruben Studdard, Kelly Clarkson, and Tamyra Gray—which, in its treacle and glee, recalled nothing so much as The Lawrence Welk Show.

Meanwhile, non-reality-TV stars—mere celebrity actors and singers who worked really, really hard to get where they are today—must continue their yeoman’s duty of serving as avatars of dysfunction (even if it means moonwalking to jail).

We keep them on as temp workers—watching their TV shows and movies or not, buying their albums or not, depending on our whims. We not-so-secretly hope they’ll crash big-time. (Ben and J.Lo. Gigli.) Until Clay succumbs to an autoerotic misadventure, or Bachelor Bob cheats on Estella (preferably with the paperboy), or Estella’s sex video (preferably with Tamyra) ends up on the Internet, they’re all we have.