The Mercer lobby at dusk. A great hush envelops the room, as if there has been a demand that tones are kept classy and collegial, but over the faint clink of silverware on china, some things carry.

“The most important step after this conversation is to see Richard Serra … ”

“The political nature of the firm is such that you will not be able to develop those ideas autonomously … ”

“As it is written, this is a man who has never gotten his way in life, and we must have someone who reflects the vulnerability of that position … ”

“Richard Gere!”

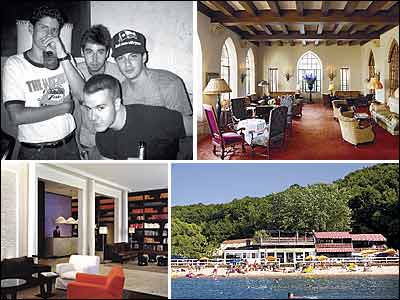

In a corner nook, beneath the flattering white light of a rectangular hanging lamp, sits André Balazs, sybarite and businessman, the proprietor of the Mercer and a small empire of exceptional hotels, as well as a newly minted condo developer, or, in his parlance, a “creator” of “residences.” You could call him Soho royalty, and he would like that: Balazs has lived in the neighborhood since 1984, what some might call the beginning of the end, and he can tell stories of what it was like to live above the old Dean & DeLuca, just down Prince Street from where we’re sitting, or how, during a blizzard, he scaled a snowbank with Calvin Klein to visit Keith McNally in the semi-constructed Pravda, the three of them underground in the storm’s dead silence.

André Balazs is a small man and very handsome. This is his real name, though he is not French, as you might fairly assume. At 48, his face is barely creased with age, and there is nothing about him that is blemished—the shave is close, hair freshly cut, expensively understated clothes well pressed. A gray-stone pot of tea sits in front of him, and I order one as well.

“That’s good,” he says. “That’s good.”

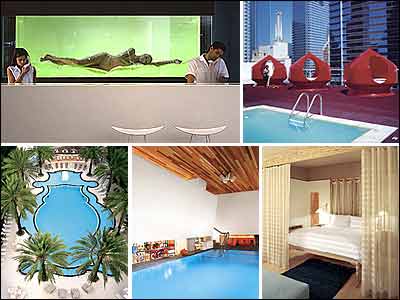

It’s a compliment, I suppose, because Balazs is one of the city’s great authorities on sophisticated living. Creator, though it sounds silly, is perhaps the best description of what he does. He does not aggressively finance and acquire properties, and his forte is not managing properties or being a real-estate investor. He is a performer: Much like a nightclub impresario, his own investment is secondary to his ability to bring money and architecture together to create a significant hotel experience, and more than any other hotelier today, he has proved himself able to keep the cool people when they come. The Raleigh in South Beach, the Sunset Strip’s Chateau Marmont, Sunset Beach on Shelter Island, L.A.’s two Standard hotels, Hotel QT in Times Square—these are all his. Each provides a socially salubrious experience, a kind of swishy Club Med for young urban tastemakers. The obvious comparison is Ian Schrager and his battalion of boutique hotels, but Balazs’s hotels are far more unique and eclectically designed. He does a little advertising, and the press has been almost universally kind to him and his properties.

As careful as a politician in his speech, Balazs is quick to say that his hotels and new condos, Richard Gluckman’s One Kenmare Square and Jean Nouvel’s 40 Mercer Residences, are “not for everyone, but they appeal in a strong way to a very select group.” Very clever, Mr. Balazs, for who can resist when the select group has traditionally included movie stars, like his current girlfriend, Uma Thurman, or Russell Crowe, he of the telephone toss at a Mercer desk clerk this summer, or, perhaps, Rupert Murdoch and Wendi Deng, who stayed in the Mercer for months before they purchased their Soho apartment, now on sale for $28 million. The Murdochs commissioned Paris-based furniture and interior designer Christian Liaigre, designer of the Mercer, to design their entire apartment, “soup to nuts,” says Balazs. This morning, the “House & Home” section of the New York Times quoted Deng on her vision for her apartment. “We just thought we want something like that style [of the Mercer],” she said. “But better.”

“Ah,” Balazs says uneasily, sipping his tea. “That’s very, very sweet.”

Balazs’s hotels are wonderful, frivolous, artistically free, as true to the spirit of boutique-hotel godfather Morris Lapidus as good-time icons like the Paramount or Balthazar or the Maritime, but none of them will necessarily be landmarked buildings—they are about temporal experience, and some are only as good as the guests housed within. Today, Balazs wants to compete in a bigger game. One Kenmare Square, whose 53 apartments all sold before the interiors went into the building, was the initial gambit, and not everybody thinks it’s a masterpiece. “It’s a unique solution to the problem of the site,” says Balazs. The building has a wave in it like a modern Finnish vase and is set on a sorry excuse for a “square” on Lafayette Street below Spring. “If there was one thing I’d do differently, I don’t think the windows, the glass, is light enough—the darkness did surprise me,” says Balazs. “It gives it a slightly ominous look.”

Creating a building even better than the Mercer is Balazs’s current fixation as he enters the façade-finishing phase of construction on 40 Mercer Street, a fifteen-story condo building between Broadway and Mercer on Grand, to be completed by next August. Prices range from $2.3 million for 1,222 square feet to $12.5 million for a duplex with a private pool. Twenty of the 40 apartments are sold. It is the first residential project in the U.S. by the neo-modernist Nouvel, known for wearing black every day of the year except during the month he summers in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, when he wears only white. It is glass, like everything that is new at the tippy-top of the market today, all these voyeurs hovering in their pseudo-case-study apartments up in the downtown sky.

“The challenge is, how do you build an unabashedly modern building in a historical neighborhood?” says Balazs. “Do you do something like the Tribeca Grand and try to pretend the building was built a hundred years ago? Or do you probe deep and try to find the essence and build something new but appropriate? To me, the Disney-esque approach of doing a faux building was just repulsive. To me, it violated the very Soho that I’ve known for 25 years. Soho is a gritty former mercantile area that has, of course, evolved into the most bourgeois neighborhood in New York. If the reason this district is landmarked is because at one time it embraced a tremendous modernism of the time, then the most authentic thing is to approach it anew.”

It was a sunny day indeed when Herbert Muschamp wrote his review of the building upon its approval by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2001, calling the decision of “breathtaking importance for the future of architecture in New York.” In one of Muschamp’s greater flights of fancy, he wrote that the building was “made for Moody’s ‘Mood for Love’ as performed by King Pleasure, on a rainy weekday afternoon, downtown… . Not least, this design is about sex.”

One rainy day, Balazs looks up at the great concrete skeleton of his building from in front of the sex-aids dispensary Toys in Babeland. “This is everything I wished I could have had at the lofts in Soho I’ve lived in, everything I loved having at the Mercer, and everything I wished I could have at the Mercer,” says Balazs. He realizes where he is standing and chuckles.

It certainly sounds nice to have in-house parking and a concierge and a pool, and to be able to move the seventeen-by-twenty-foot sheets of glass that are your windows with an electronic button. There is a shared bathhouse, including a sauna and steam room—“for birthday parties!” says Balazs, who seems to have made it a personal mission to bring shvitzing to the elite; he is a patron of the Tenth Street Baths, his downscale Hotel QT in Times Square has a sauna and steam room, and the new Standard in Miami is more a spa than a hotel, including a large hammam. Baden-Baden was the first hotel Balazs visited as a kid. “A spectacle,” he says. “I remember it was everything.”

The notion is that at 40 Mercer, with a buyer’s brochure that includes a children’s book about two Soho dogs who fall in love and move into the building, you can live as though you are at a fabulous André Balazs hotel every day. On the building’s top floor, a view of the spires of downtown spread at his feet, and romantically enhanced by the rare graffitied water tower, Balazs wades his Prada shoes through the construction crew’s cigarette butts and Pepsi cans floating in deep puddles. “I don’t know if I’ll move in here,” he says, a smile spreading over his face. “I haven’t decided.”

Balazs is in the enviable position of having his celebrity precede him these days. To have Uma Thurman as a girlfriend could provide mystique to Michael Bloomberg. There is not a hint of the striver about Balazs, though his voice bears traces of a Boston accent. The son of educated Hungarian immigrants who left their country during World War II, resettling in Sweden and then Cambridge, Massachusetts, Balazs grew up in a Swedish-Danish-designed home. “My parents always kid that the things I’m into today are the same things they had back then,” he says. His father taught at Harvard Medical School, and his mother is a psychologist. Balazs went to prep school and doesn’t have particularly fond memories of Cambridge. “It’s surprisingly close-minded,” he says. “It’s scared. There’s a fearfulness there. To me, the most charming quality of New York is its open-mindedness.” At Cornell University, he studied humanities and wrote short stories with Harold Brodkey, a mentor and friend, and started a Playbill-type publication for upstate New York rock concerts. After college, he attended a joint journalism-and-business master’s program at Columbia University.

“For my thesis, I checked into the Bowery Mission,” he says. “I lived there for a week, as though I were homeless. There was one guy who had been an accountant, became an alcoholic, and his very bourgeois and seemingly secure life changed into complete abandonment and loss. Despite everything that the shelter could offer—shelter, food, clothing—all people wanted was a woman, a place of their own, and a job, in that sequence.”

Balazs decided against journalism, though he worked briefly for David Garth on Bess Myerson’s Senate campaign. Then father and son founded Biomatrix, a Ridgefield, New Jersey–based biotech company, and Balazs was able to secure his nest egg. It was the mid-eighties, and he was living in a fifth-floor loft in a Greene Street building otherwise occupied by rag merchants. He went to nightclubs. He met Eric Goode, who was founding the legendary M.K. “Eric approached me and said, ‘Do you want to do a nightclub? We need more money,’ ” says Balazs. “There was a big dichotomy between the life I was leading in New Jersey and everything I was interested in. I had a desire to merge the work and private life.”

Today, sitting in a red chair in his jewel of an office in the Puck Building, Balazs is surrounded by well-thumbed design books and mementos, like a candid photo of Helmut and June Newton (Balazs was at the hospital when Newton passed away, after a car accident outside the Chateau Marmont). A faux–Egon Schiele drawing leans against a wall: Balazs had it commissioned as a lark, collaborating with a group of artists to produce a show of fake masters at a gallery in Japan. It was performance art—they estimated the cost of materials to make the painting, an hourly wage for the artist, and expenses like the cost of a six-pack of beer, then calculated the difference of a real Schiele. Balazs calls this spread the “fetish value.”

“It’s sad, in some ways, what happened to Soho,” says Balazs. “It is still the most complete and yet most unique neighborhood in the city. It is missing the art world. That’s one of the sad and inevitable evolutions. But it is an evolution, and instead of it comes something else.”

Earlier, in the bustle of Mercer Street, with its new cobblestones and aging bistros, high-stepping models and sauntering tourists, Sunglass Hut and Yohji Yamamoto, he says, “I like to think of 40 Mercer as the last artwork in this neighborhood.”