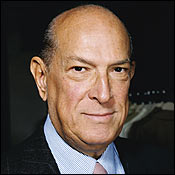

Oscar de la Renta is trying to eat his hamburger. This is a challenge, what with the burnished ladies and regal gentlemen sauntering by every few minutes to say hello, to say he looks terrific, to ask after his wife, to ask after the First Lady (and the former First Lady), and to congratulate him on his continued success. The 72-year-old fashion designer is seated at a central table inside Michael’s, the midtown restaurant favored by powerful people who like to be observed eating lunch by fellow powerful people, an establishment where the De la Renta presence—impossibly crisp suit, elongated resort-bronzed face, narrow brown eyes—is a familiar one.

“You know, as I get older and I look back, I think that I have been probably working harder now than I’ve worked in my whole life,” he says, having just exchanged hellos with yet another “good friend” before returning to the subject at hand: how, when most of his contemporaries are either happily retired, governed by clunky conglomerates, or no longer living, he is launching new lines, developing young talent, wooing younger women, opening his first boutiques, revamping, reviving, rethinking, cementing a plan of succession for the day when “I will no longer be around.”

De la Renta, who was born in the Dominican Republic and always seems to be slyly grinning at a private joke, speaks in a charismatic, heavily accented purr. “I remember when I was a little boy living in the island that I come from, time went soooo slow,” he continues. “Now … well, very seldom do I go out to lunch. When I started working—going back 25, 30 years ago—I went out to lunch every single day, you know? But I don’t drink—well, I like to have a glass of wine at night—but if I drink during the day now, I get very sleepy. Please pardon me. I am famished and need to eat for a moment.”

He relieves the medium-cooked hamburger of its bun. Using a fork and knife, he cuts himself a small piece of meat. Carefully dipping it into some Dijon mustard, he brings the bite to his lips, when suddenly—

“Oscar, hel-lo dear.”

He is forced to go hungry a little longer.

People are saying hello more than usual this afternoon, and this is just fine. (“I hate to be alone,” De la Renta is fond of saying. “More than anything, I hate to be alone.”) It’s the day before President Bush’s second inauguration, 24 hours before Laura Bush will appear—at the podium as her husband is sworn in as leader of the free world, at the balls afterward where she’ll celebrate this swearing-in—wearing head-to-toe De la Renta, a series of outfits that will be widely applauded in the following days. It is all very similar to what Hillary Clinton had experienced during her husband’s second inauguration, way back in a different America.

“Congratu-laaa-tions with the inaugu-raaa-tion,” the woman coos, sounding like she’s praising the winner of a middle-school science fair. De la Renta stands up—he is a man who always stands in the presence of women—kisses the woman’s professionally exfoliated cheek, and thanks her graciously. Then, once she’s vanished, he takes his seat, sighs, sips his Pellegrino, and, at last, devours his hamburger in quick, minuscule bites. After a moment, he leans in to his table companion and whispers, “Do you know who her husband is? He’s Gerry Schoenfeld. He owns all the Shubert theaters.”

It is a perplexing, and revealing, moment. Here is De la Renta—consummate host of the city, the insider’s insider—making an outsider’s comment, a striver’s comment, the sort of utterance being whispered just then by those seated at less-prime tables, living less-prime lives. Do you know who that is? That’s Oscar de la Renta. He designs gowns for First Ladies.

You can be having dinner with Oscar and the Clintons, and he’s a vivacious host who takes care of everything,” says Vogue editor Anna Wintour, summing up the charming bipolarity that makes Oscar, Oscar. “Then, after the meal, he’ll go back into the kitchen and play dominoes with everyone who prepared the meal.”It’s an approach to life that guides De la Renta’s business as well. He’s always been something of a throwback, a reminder of an opulent, ruffled, conservatively glamorous era that in all likelihood never really existed. But he’s also up-to-the-minute, having recently introduced a new line, O Oscar, in which no single piece retails for more than a hundred dollars. On Monday, under the tents in Bryant Park, the designer will show his fall collection—his 40th year doing so since leaving his post at Elizabeth Arden in 1965 to design his own label. In that time, he’s built a sizable personal fortune (estimated net worth: $100 million, making him, by one list, the 29th richest Latino in America) as well as one of the more eclectic, iconic social networks of anyone in town (close friends: the Clintons, the Kissingers, Sarah Jessica Parker, Gore Vidal, the doorman of the Ritz). As the fashion world has gradually mutated into a blander, more corporate beast, he’s remained a constant: the elegant gent who makes clothes for elegant women, designer of choice for ladies who lunch and First Ladies like Jackie Kennedy and Nancy Reagan and Hillary Clinton and, most recently, Laura Bush.

These days, he’s gearing up to capitalize on this legacy. In an era in which most major designers have watched their companies flounder after being sold to corporate conglomerates—Donna Karan to LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton; Gucci to Pinault-Printemps-Redoute—De la Renta is the last of the independent old guard, and he’s using it to his advantage. “I have resisted corporate ownership,” he says, sipping a decaf coffee after lunch. “Not that I haven’t been tempted. I have had offers in the past”—he declines to go into specifics—“but I always am very worried about the private investors. From the moment you sell a big percentage of your business, you know that you no longer control your business. I always thought, If I had private investors, I’d be able to expand my business, but we’re doing it now without any outside help. We’re masters of our own destinies.”

The key word in that last sentence is we. While De la Renta’s company bears one name—his own, punctuated by his famously suave signature—it has become a family affair. We, specifically, constitutes two people in particular: Eliza Bolen, the youngest daughter of De la Renta’s second wife, Annette, and for ten years, vice-president of the $250 million licensing department, and her husband, Alex Bolen, who was named the company’s chief executive when Jeffry Aronsson jumped ship for the corporate gloss of LVMH after nearly a decade with De la Renta. Spend time in De la Renta’s bustling, creamily lit headquarters, one of the last where wrinkled seamstresses hunch over drafting tables stitching the clothes in-house—and you’ll hear a great deal about how we are changing De la Renta. We are involved in exciting new developments (in addition to O Oscar, there’s a fledgling home collection overseen by Miles Redd). We are only starting to tap into our true brand recognition (a Madison Avenue boutique opened in November, followed by Miami, with Las Vegas on the way and Europe in the crosshairs). We are hoping to turn an elite brand into a global empire catering to a larger clientele (much like Ralph Lauren, to name the visionary designer we most admire).

Bolen’s appointment was something of a shock: Was he really the best man for the job? Or was this merely the crass hand of nepotism? A carnivorously ambitious, West Virginia–raised 37-year-old, with close-cropped sandy hair, he has no background in fashion. (Which is becoming more commonplace; Robert Polet, Gucci’s new CEO, comes from the world of frozen foods.) He worked in finance, founding and then selling an asset-management company before joining Bear Stearns, and, as the market stalled, consulted part-time for De la Renta while the designer searched for a new CEO. It didn’t take long for Bolen to win over the fashion set. “A lot of what you’re seeing with Oscar has to do with Alex coming onboard,” says Wintour. “He’s come up with some kind of master plan to expand Oscar’s empire, and I think it’s a correct one. Oscar deserves a bigger platform.”

“When the chief-executive offer first came up with Oscar, I was more than a little hesitant,” Bolen says, sitting in his corner office, adjacent to his wife’s. “Working with my wife, with my father-in-law—it just seemed like a recipe for disaster.” Furthermore, the fashion world is populated by a different personality type—affectedly eccentric, unpredictably sensitive—than he was used to on Wall Street. “On Wall Street, let’s face it, everything is motivated by money,” he says. “In fashion, everyone understands it is a business, but you’re still really dealing with … I mean, these people are really artists. I think, for me, one of the biggest challenges has been learning patience, and how to manage personalities.”

The personal dynamic between Bolen and De la Renta is a curious and entertaining one to observe. De la Renta likes to joke, always in the presence of his son-in-law CEO, that Bolen will one day fire him. (“I think you’re safe for a few more days,” Bolen replies.) Bolen, who always seems to be within fifteen feet of De la Renta, barking about various business coups and pitfalls, often can’t help but make design suggestions. (“Alex,” De la Renta replies, “fashion school is on the corner. I believe they have night classes.”) As personalities, the two are polar opposites. Bolen wears a tie because he’s the boss; De la Renta because “it’s one of my very few complexes. I see people in a colorful shirt and I think, My God, I would really love to wear that, but then I am afraid that when I walk into the door, the host will say, ‘I’m sorry, but the Latin band walks through that other door.’ ”

De la Renta likes to joke that his son-in-law Alex Bolen will one day fire him. “I think you’re safe for a few more days,” Alex replies.

The designer’s capitalistic urges are cloaked by courtesy, indefatigable charm, and an ability to talk for hours about the texture of fabrics. Bolen is brusque, fast-talking, a natural-born intimidator who turns almost any subject of conversation into one about the business’s future. (As it happens, employing his stepdaughter and son-in-law almost never became an option: When De la Renta asked Annette to marry him, in 1989, she didn’t say yes immediately. “She didn’t want to get married,” he says with a laugh. “She thought there was no need to. But I’m a Latino, so I believe in the institution.”)

The Bolens’ effect on the De la Renta identity is most evident in the designer’s recent—and successful—push to court younger women. Eliza Bolen will often look at his designs and proclaim, “My friends will never wear this,” at which point De la Renta does some rethinking. At the same time, the designer views his current renaissance in sociocultural terms, defining himself as something of a postfeminist designer who made his mark in a prefeminist age. “Certainly, what is exciting about fashion today, especially in my field, is that never in history has there been a time when a woman has as much control over her destiny as she does today,” he says. “I always tell this story: When I started, the woman went to the store to buy a dress. She saw it in pink and red, and then she remembered that the husband, who is probably going to pay for the dress, loves it in pink. So she buys the pink. Today, the same woman goes to the store and remembers the husband likes pink, and she buys the red.

“I think that probably what has made my business so successful today is because the most important consumer now is the professional woman,” he continues. “Back in the seventies and eighties, she was going into the men’s world. She felt she had to dress in very, very boring clothes. And then, you know, a woman knows that she can look great, that being a woman is an asset. And this is what I have always known. And so, perhaps, this is my time.”

It’s been rumored that the true motive behind the current rush of activity is to ready the company for a sale, and while Alex admits that “the crude fact is that everything is for sale, for a price,” he is adamant in pointing out that “there is no endgame plan,” adding that keeping the business in the family is critical to preserving the De la Renta identity.

But family can be a complicated affair, a fact De la Renta has learned watching his adopted son, Moises, come of age—and take up interest in fashion. These days, the 20-year-old can be seen milling around the studio—a taciturn, handsome, frenetic kid who has been known to spend his nights crushed into sleek banquettes with Paris Hilton and other members of the empire-spawn diaspora. Last year, Moises dropped out of Marymount Manhattan College, and decided, seemingly on a whim, to become a designer, something his father struggles to process. “Moises has always needed a lot of help, which you can get in school, but once you get to college, you have to seek that help; it doesn’t come to you,” De la Renta says at Michael’s. “His first year in college he did really badly. He came to me and he said he didn’t want to stay. I felt unbelievably bad about it because I kept saying to him, ‘Moises, as a father, all I can give you is an education. I lost my mother when I was very young, and I have been working since I was 21 years old, and I didn’t have the opportunities that you have.’ But, you know, young people don’t understand.”

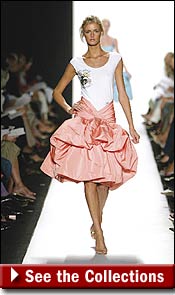

Moises, who’s studying at F.I.T., started working in the studio last year, asking for the lowest position possible, in the pattern room. But such humility had its limits. His first stab at designing was a hipster-looking T-shirt emblazoned with the logo ROCK AND ROLL, HEART & SOUL that his father featured in his fall runway show, paired with a ball skirt, an unexpected marriage of the old and new school. Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar raved about the edgy elegance, and the T-shirt, which sells for $150 and is prominently featured in the upcoming Mario Sorrenti–photographed ad campaign, ended up being the first item purchased at the Madison Avenue boutique. Moises decided that he was now a professional designer, too. On January 13, he debuted a small, mainly denim collection of his own at NA, Damon Dash’s nightclub, at a shoddily executed group show that was the opposite of everything his father’s name—which Moises uses for his line after deciding against “Moi”—has come to represent. (The event was produced by a company called Stop the Glamour.) Given his surname, Moises had little trouble attracting a certain kind of attention. The Post, for instance, wrote a profile of Moises (headline: THE SON ALSO RISES), describing him as building “his own fashion empire.”

“I was very upset about that article,” De la Renta says one afternoon in his office. “I think he has talent, a certain eye. Of course, parents are always very biased, but I do think he has something. I try to tell him, ‘You only get that kind of attention once.’ ”

“I always tell Hillary not to wear black. The problem is that everything else she has is mine, and with Mrs. Bush also wearing something of mine today … ”

Over lunch, he goes into more depth: “Moises did a little line, five or six pieces. But that doesn’t make a fashion designer. I say, ‘Moises, when I started the business, I became well known because I was making clothes that were bought by a store, and women went to that store and bought those clothes, and then people started to talk about me.’ Today, unfortunately, you have a lot of young kids who get a tremendous amount of press who haven’t sold a single dress. It’s fantastic and great to have your clothes photographed in Vogue, but”—he looks down at his $28 hamburger, which he will eventually insist on paying for—“that doesn’t buy you a meal.”

In 1983, the year before Moises was born, De la Renta’s first wife, Françoise, former editor of French Vogue, died of cancer. He and Françoise—whom De la Renta married in 1967—were a beloved institution, their East Side apartment known as the place to find Norman Mailer talking to Alan Greenspan behind the back of Candice Bergen. (De la Renta’s current wife, then Annette Reed, was also a fixture at such gatherings.) In 1980, the metaphysics of the De la Rentas’ dinner parties were deconstructed in The New York Times Magazine, in an article that deemed their home a “latter-day salon” with influence on the “New York–Washington axis.” To many, Françoise, who played no formal role in the company, was the secret weapon to De la Renta’s success—forging many of the relationships that created his deep foundation in society. “She is the éminence grise of Oscar,” Marie-Helene de Rothschild told the Times Magazine. (Similar remarks are made about Annette. “She makes Oscar more extraordinary,” says Wintour. “She is his best friend, his companion, his judge, his critic.”) He and Françoise had no children, and her sudden death left De la Renta without a family.

“That’s the time I adopted my son, between marriages,” De la Renta says, his grin subsiding a bit, his expression growing uncommonly solemn. “I never thought that I would get married again. I thought my son and I would have each other. I am very much involved in an orphanage in the Dominican Republic, and he was the youngest orphan. I’ve known him since he was 24 hours old.” Moises is De la Renta’s emotional core, his connection to his past, and his worries are indicative of an upscale version of the classic immigrant’s dilemma: De la Renta’s son was adopted into the kind of glamorous American world De la Renta (whose own father ran an insurance company) had to work to gain membership in. “He’s the sweetest, nicest human being,” De la Renta says of Moises. “But he is unbelievably naïve. He has a heart of gold. If you give him $10 and tell him ‘Here, pay for a cab,’ he will walk outside and find a homeless person. He has no sense of self-preservation.”

At which point De la Renta sips his coffee silently. It’s time to change the subject.

“What’s Senator Clinton wearing?” the designer wants to know. It’s Inauguration Day and De la Renta is in his studio, too busy tweaking his new collection to attend the festivities. He is squinting at Chrissy Haldis, a tall, willowy, and by all accounts mannequin-mute brunette who has served as his house model for the past two collections. She stands rotating in slow circles, sheathed in rare, velvety Uzbekistani fabric that, when hemmed and cut, will become a long coat retailing in the neighborhood of $10,000. In De la Renta’s adjoining office, the inauguration is being broadcast over the Internet—there is Laura Bush, pert and stately in a pearly De la Renta cashmere dress, though the designer is currently concerned about the clothes another client, Hillary Clinton, has chosen for the event.

“She’s wearing black,” someone points out.

De la Renta frowns. “What?”

“It’s a black jacket, and a—”

He cuts her off. “Oh, I always tell Senator Clinton …” He pauses delicately. “Well, I mean, I’m sure she looks beautiful. Hillary is a beautiful woman. But I always tell her not to wear black. She looks tough in black”—he tenses his fists and jaw to illustrate his point—“and she is more than just a tough lady. The problem is that everything else she has, every other piece of clothing that’s not black, is mine, and with Mrs. Bush also wearing something of mine today … ”

After a moment, De la Renta simply laughs. The designer, who grew up under a dictatorship, seems to find politics most compelling, not as an engine of policy and social change, but as a theater of bombastic personalities kept in line by social formality.

“I’m a nonpartisan voter,” he says with a smile. “I vote for the man, not the party. I voted for Clinton, but I voted for Bush. I also voted for Reagan.” He pauses. “Black! I cannot believe she’s wearing black!”

De la Renta’s interest in the marketing of femininity dates back to age 7, when the designer, playing in his large backyard, attempted to manufacture perfume. “I thought if I woke up very early, I could collect the dewdrops off the flowers, I could make perfume,” he recalls. “And then I realized the perfume was not involved in the dewdrops. I couldn’t understand how the liquid comes out of the flower!”

Imagine the designer back then, the only boy among six sisters growing up in a protective Dominican family. (“While other boys were playing in the street, of course I was not.”) At 18, he left the island for Spain to become a painter. His mother, sick with multiple sclerosis, allowed him to go, knowing she wouldn’t see him again. His father was skeptical about art. To prove to his father that he could earn money, De la Renta took fashion-illustrator jobs at newspapers. He was talented, and he had a certain verve that allowed him access into the world of fashion. Soon he was hired by Balenciaga as an illustrator, then as a designer. He moved to Paris. He painted less. In 1963, feeling the future of fashion was in ready-to-wear, De la Renta moved to New York for a job with Elizabeth Arden. He met Alex Liberman, the editorial director at Condé Nast. And John Fairchild, the editor of Women’s Wear Daily. And Diana Vreeland, the editor of Vogue. Within two years, he had his own line. By 1971, he was one of the most established names in the business and had just bought a country estate in Kent, Connecticut, for $110,000.

It was the sort of speedy ascent that instills in someone an innate grasp of the importance of first impressions. Who better to understand what a First Lady goes through?

Ask De La Renta why First Ladies feel so comfortable with him, and first he’ll tell a joke—“I hope it’s not my age”—before explaining that, much like himself, the First Lady is the ultimate outsider turned insider. “When you come from the middle of the country, and you arrive in a certain society, I think it’s very difficult for every First Lady,” he says. “After all, she’s not elected. The men are elected. But people do have expectations—more in this country than any other country. Do you know who Chirac’s wife is? Mitterrand’s? Exactly. Here people do care, people are looking. And we are so influenced by what we see visually, you know?”

Hence the gnawing effect Hillary’s black outfit has on De la Renta. When he started to dress Clinton, the first thing he did was eliminate black from her wardrobe. “The perception of what people had of her was different than what they have now,” he explains. “First of all, she is an extremely intelligent person. And caring person. And loving person. And full of charm. And full of laughter. And people never really saw her that way. So I said, ‘Let’s stop wearing black. Let’s dress you now in pale blue and pale pink.’ ” A switch to pastels isn’t quite the same as passing, say, universal health care, though the public perception of Clinton did change tremendously, which certainly came in handy during her Senate run.

The designer was surprised when Laura Bush approached him. “With Mrs. Bush, Vogue magazine was going to photograph her when she was going into the White House,” he recalls. “Anna Wintour called me and asked if I would send some clothes to Vogue. I told Anna, ‘You know, I have been so closely identified with Mrs. Clinton that I don’t think Mrs. Bush would want to be photographed in my clothes.’ She said, ‘No! No! No! Please send some clothes.’ So I did send some clothes, and apparently Mrs. Bush arrived at the shoot in a red suit of mine that she had bought in Austin, Texas. She asked if there were any other clothes of mine there, so they showed her, and she chose another pantsuit for the shoot.” De la Renta sent the First Lady a thank-you note, and shortly after received a call from the White House: Mrs. Bush was going to be in New York and wanted to stop by his studio. “This was the very first First Lady that had come to Seventh Avenue, which I found extremely nice and kind. The very first time I met her—have you ever seen her in person? No?—well, I have never seen blue eyes like hers. They’re like sapphires! The very first time I met her, I said to her, ‘Mrs. Bush, I’m going to ask you a very indiscreet question, and I hope that you won’t consider it rude. Do you wear contact lenses?’ She laughed and said, ‘No, I don’t.’ Ha!”

Later that morning, reps for Penélope Cruz call the office to let it be known that the actress would like to wear De la Renta to the Oscars—possibly-maybe-definitely —but would need to see some sketches first, before finalizing her decision. While De la Renta speaks highly of many stars—he credits Sarah Jessica Parker with having helped revive his image by fawning over a De la Renta gown in an episode of Sex and the City—he is not particularly well versed in celebrity, and in general doesn’t admire actresses.

“They are more of a hassle to deal with than anything else,” he says. “They tend to be insecure people. Insecure and capricious. These are two bad qualities.”

He turns to his assistant.

“Send her the sketches,” he says.

A week after Inauguration Day, De la Renta flies down to Miami to celebrate the opening of his store, which is located in the luxurious Bal Harbour Shops mall. The boutique—a cozy, brightly lit, high-ceilinged quarters with walls tiled in stone from a Dominican quarry near De la Renta’s home there—is packed with types who, depending on your aesthetic tastes, are either freakishly stunning or stunningly freakish: the face-lifted, the orange-skinned, the heavily bejeweled, all with suspiciously white teeth. They drink passion-fruit Bellinis and make good use of the word fabulous. A 15-year-old model from South Africa who looks 25 weaves her way through the room in a series of De la Renta gowns being stroked by strangers. Alex is on hand, ever the micromanager—picking up a shawl that fell off its hanger, shaking hands, keeping an eye on De la Renta, who’s dapper in a dark pin-striped suit, at all times. When asked how he feels about the store, he says, “The cash registers apparently are working, so that’s a plus.” Then he notices something in the distance and excuses himself. “Oh, Oscar’s talking to the store’s landlord. I need to go make sure he doesn’t say something he’s not supposed to.”

Annette de la Renta spends the majority of the event sandwiched inside a display, half-hidden by two of her husband’s gowns, talking with Miles Redd, the magnetic, high-cheeked, Georgia-born creative director for Oscar de la Renta Home. As Redd explains his role in the store’s look—“These plaster palm trees,” he says, pointing at the ones framing two gigantic mirrors, “that’s me”—a drag queen named Elaine saunters over to Annette, who smiles through her teeth.

“Oh, let me get a picture of the two of you,” says Redd, pulling out his camera phone. Annette shakes her head.

“Come on! I’ll e-mail it to Eliza!”

Annette, shy but witty, throws an arm around the transvestite.

“Okay. Take a picture.”

After the opening, De la Renta holds a dinner at André Balazs’s Raleigh hotel—a gathering of about 40 friends, not clients. Paella is cooked out by the pool. Jane Holzer kisses De la Renta’s cheeks; so does the photographer Bruce Webber. As everyone takes their seats at a long, family-style dinner, whispers can be heard that “Lenny has landed”—Lenny Kravitz has dropped by. In the presence of socialites, Kravitz, in a conservative gray suit and tie, appears oddly boyish, calling everyone “Sir” and “Miss.” The rock star sits next to De la Renta, discussing his own upcoming clothing line. Before the sorbet course, Paul Wilmot, the ubiquitous publicist, decides he is the man to make a toast. “I think tonight is a night that’s all about one thing: first names,” he says, inaccurately. “It’s a night where you’d say, ‘I went to this store owned by a guy named Oscar. Then I had dinner with a guy named Lenny. And a guy named Bruce. And so … well, to first names.”

“To first names!”

De la Renta, as always, is at once the central figure and the man off to the side, checking everyone out, making sure they are okay.

“I’m tellin’ ya,” says his bodyguard and driver, a sardonic guy named Lou Perno, who speaks with a heavy Queens accent. “Mr. De la Renta is as comfortable talking to a janitor as he is a president. The man knows everyone. One time, I’m with Oscar, and we’re at some New York hotel to meet the president of the Dominican Republic. We’re in the elevator, and it stops on one floor, and there’s Gerald Ford and his wife! Both of them in tennis clothes! I’m like, ‘I can’t believe it’s Gerald Ford.’ And what’s he do? Immediately he leaps at Mr. De la Renta and gives him this huge hug. When he got off the elevator, I turned to Mr. De la Renta and said, ‘Is there anyone you don’t know?’ ”

At just that moment, De la Renta comes over to say that he’s tired—he has an early flight in the morning so he can work through the weekend on his collection. But before heading off to bed, he puts a tanned hand on Lou’s shoulder, squeezes, and says, “There are so, so many people I don’t know.”

He seems to mean it.