SOLUTION 1

Corby Kummer

senior editor of The Atlantic and author of The Joy of Coffee

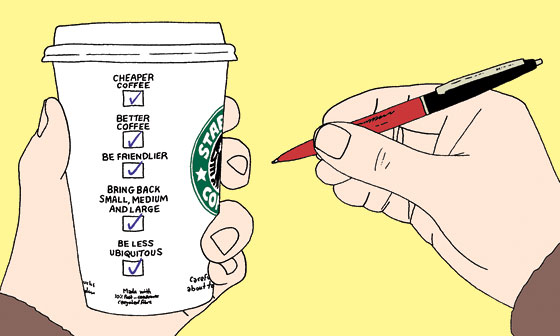

Fix the food. It’s dull, predictable, often has the texture of sawdust, and changes so seldom you’re certain it’s ancient even when it isn’t.

Fix the coffee. Yes, Starbucks routinely overroasts—but it doesn’t overroast well, the way those artful Italians, who often use much, much more mediocre beans, do. Plenty of the beans Starbucks starts with are more than decent, even distinctive. But uniform overroasting, and central roasting plants that ship coffee halfway across the country, almost guarantee coffee that tastes uniform and stale.

Train baristas to know what they’re talking about. Now that you’ve bought the company that makes the Clover—the showy, theatrical single-cup brewer which I was entertained by and wrote about here—pick beans that taste better brewed than as espresso, roast them a little less, and tell your sales associates enough so they can really sell them.

Make more locations feel like home. Boston, where I live, has three of the numberless Starbucks where the staff always knows you and is lighthearted and friendly to everyone, where customers nod and greet each other, where people take pride in leaving behind offbeat reading material. Clone their managers.

SOLUTION 2

Danny Meyer restaurateur

Starbucks has put an entire adult population through Coffee University. To grow, it now must build a graduate school for the multitudes it has prepared for an advanced degree. A new generation of stores run by passionate coffee geeks has lapped Starbucks qualitatively, and while none has the scale to threaten Starbucks’ market dominance, collectively they pose a huge threat to the underpinning of Starbucks’ historic business advantage—a pricing justification keyed to being “the best.” If I were in charge, I’d buy (or pay enormous consulting fees to) four of the smaller, elite players from across the world who are doing it right: Monmouth Coffee (London), Blue Bottle (San Francisco–Oakland), Intelligentsia (Chicago), and Joe the Art of Coffee (New York). Drawing on their collective intelligence, I’d develop the ultimate connoisseur’s coffee bar—based on a relentless pursuit of the superior cup of coffee. I’d launch these fresh stores as a separate new luxury brand with the working title STARbeans—that would confer a halo effect on Starbucks coffee, as Purple Label has on Polo Ralph Lauren. I’d bring in folks from my team as chief hospitality and service consultants and would dispense with specialty drinks and most of the food. At STARbeans, we’d charge 25 to 50 percent more than run-of-the-mill Starbucks outlets and we’d scale up at a slow enough pace to assure quality, hospitality, and prestige.

SOLUTION 3

Jonathan Rubinstein

owner of Joe the Art of Coffee

Focus on the three elements of excellent coffee:

Beans: Their roasting needs to be adjusted to fit the more sophisticated palates Americans now have. People want to taste coffee—not just roast. Customers also want their beans to be freshly ground seconds before brewing a pot of coffee—not pre-ground before delivery, or ground in the morning to last the entire day.

Baristas: Spend the money and train them well to be coffee artisans. A three-hour retraining session doesn’t cut it. Don’t just hire button pushers on some giant robot—that goes against everything Howard Schultz originally envisioned. It’s hard to control quality with so many baristi, but that can’t be used as an excuse to become an Automat.

Espresso machines: An essential element in the third wave of coffee is the barista, something that Starbucks deemphasized completely when they chose to go to fully automatic espresso machines. It’s ironic that a second-wave pioneer like Starbucks is now in an unlikely position to join the third wave. Find a way to go back to real manual espresso machines where trained baristas have control over every drink. Oh, and please get rid of the tallsoyhalfcafpumpkinfrappuccinoinagrandecup drinks—stat!