If we’re being honest, most of us have at least some selfish aims – to make money, to win a promotion at work, and so on. But importantly, we pursue these goals while at the same time conforming to basic rules of decency. For example, if somebody helps us out, we’ll reciprocate, even if doing so costs us time or cash.

Yet there is a minority of people out there who don’t play by these rules. These selfish individuals consider other people as mere tools to be leveraged in the pursuit of their aims. They think nothing of betrayal or backstabbing, and they basically believe everyone else is in it for themselves too.

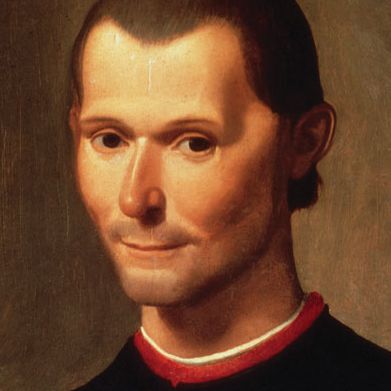

Psychologists call these people “Machiavellians,” and there’s a questionnaire that tests for this trait (one of the so-called “dark triad” of personality traits along with narcissism and psychopathy). People high in Machiavellianism are more likely to agree with statements like: It is wise to flatter important people and The best way to handle people is to tell them what they want to hear. Calling them Machiavellian is too kind. These people are basically jerks.

Now a team of Hungarian researchers from the University of Pécs has scanned the brains of high scorers on Machiavellianism while they played a simple game of trust. Reporting their results in the journal Brain and Cognition, the researchers said they found that Machiavellians’ brains went into overdrive when they encountered a partner who exhibited signs of being fair and cooperative. Why? Tamas Bereczkei and his team say it’s because the Machiavellians are immediately figuring out how to exploit the situation for their own gain.

The game involved four stages and the student participants — a mix of high and low scorers on Machiavellianism — played several times with different partners. First, the participants were given roughly $5 worth of Hungarian currency and had to decide how much to “invest” in their partner. Any money they invested was always tripled as it passed to their partner. The partner — participants thought this was another student, but really it was computer-controlled — then chose how much to return and this was pre-programmed to either be a fair amount (around ten percent above or below the initial investment) or a blatantly unfair amount (about a third of the initial investment). So, if the participant chose to invest $1.60, a typical fair return by the partner (according to the study design) would be about $1.71, whereas a typical unfair return would be about $1.25. After these transactions, the roles switched and the study participant became the trustee. Their (secretly computer-controlled) partner made an investment, which was tripled, and the participant decided how much to return, allowing them the chance to punish their partner’s earlier unfairness or to reciprocate their earlier cooperation.

As you might have guessed, the jerks — sorry, the Machiavellians — ended up with more cash at the end of the game than the comparison participants. This was mainly because, while both groups punished unfair play, the Machiavellians, unlike the non-Machiavellians, failed to respond in kind to fair returns or investments by their partner. This failure to conform to the social norm of reciprocity was paralleled by a fascinating neural difference between the two groups. Specifically, the Machiavellians showed a sharper uptick in neural activity compared with non-Machiavellians when their partner played fairly. The non-Machiavellians showed the opposite pattern, exhibiting a sharper increase in neural activity, compared with Machiavellians, when their partner was unfair. But when a partner played fairly, the non-Machs didn’t show extra brain activity — likely because, for them, like most people, this sort of reciprocity is just second nature and comes automatically.

Let’s zoom in on the specific brain areas involved. When their partner played fairly, the Machiavellians showed unusually high activity in brain areas involved in inhibition (the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, at the front of the brain) and creativity (the middle temporal gyrus, near the ears). The researchers interpret this as evidence that the jerk participants were inhibiting the human instinct to reciprocate fairness, including suppressing any emotional reaction, and simultaneously calculating how best to take advantage of their partner’s misguided sporting play.

Some brain scientists will likely balk at reading so much into these neural activity patterns. So-called “reverse inference” — where you interpret the meaning of brain activity patterns based on the functional reputation of different neural areas — is usually frowned on in neuroscience.

However, the researchers’ story does seem to fit with their prior research. For example, although psychologists say Machiavellians typically have poor empathy (including an inability to see things from other people’s perspectives), there’s evidence that they continually monitor other people’s behavior in social situations so that they can come out on top. Also, an earlier brain-imaging study found that Machiavellians showed enhanced neural activity (compared with non-Machiavellians) in a range of areas while playing a trust game, in line with the interpretation that they are always on the look out for ways to exploit other people.

In short, these new neuroimaging results suggest that when you’re mean to a jerk, his or her brain barely fires a synapse in response — it’s all that he expects from his fellow (wo)man. By contrast, if you show the jerk signs of fairness and cooperation, you’ll send his or her brain into a spin, as the manipulator works out the best way to take advantage of you. It’s a new and intriguing piece of evidence that we can add to the jigsaw puzzle of antisocial behavior.

Dr. Christian Jarrett (@Psych_Writer), a Science of Us contributing writer, is editor of the British Psychological Society’s Research Digest blog. His latest book is Great Myths of the Brain.