Emoji are like good-natured aliens, dropping into our lives by way of smartphones and spreading across the world. And, with their newfound ubiquity, linguists are just starting to figure out how they work.

It’s increasingly clear that they act like gestures, adding much-needed clues to tone that get left out as vocal speech has been flattened into text messages. But they also behave differently than regular words: As Rachael Tatman, a linguistics Ph.D. candidate at the University of Washington, is discovering, emoji are bidirectional: Not only can they express actions, but they can also directly represent spatial relationships. Emoji are a special case for her discipline — linguists disagree about whether they’re even words, and society’s use of them is maturing before their collective eyes.

This is technical, linguistic-y stuff, so probably the best way to wrap your mind around it is with a rather well-illustrated experiment that Tatman ran through her blog, Making Noise and Hearing Things. She recruited what ended up being 127 people via Twitter and presented them with a sequence of three images. After each image, she asked them to select the chain of emoji that best described what was happening in the image; then, they were asked to write a sentence describing the scene. Together, the results show how emoji can be written — and read — with two different kinds of logic.

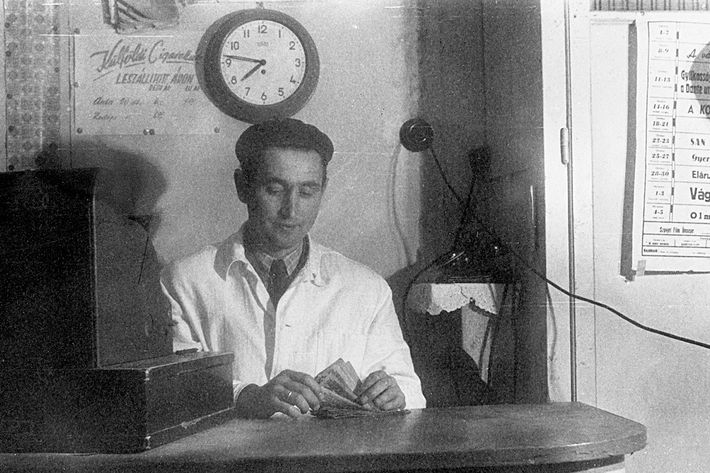

Here’s one of the photos: A Man Counting Money.

Would you write that 👨💵 or 💵👨? Over 80 percent of respondents did the former, which, Tatman says, is indicative of what linguists call an “agent-patient relationship.” There’s an agent — a subject doing a thing; in this case, a man — and a patient, or a direct object being acted upon. Because the agent-patient relationship (the action, in other words) was so clear, the emoji were arranged like words in a subject-predicate sentence. But this is not always the case.

Consider picture two: A Man Walking by a Castle.

Here, the plot thickens. There isn’t a super strong “agent-patient relationship”; red-shirt guy is casually strolling by the castle, not really doing anything to it. He’s also, one must say, on the right right of the image, and he’s one of the smaller objects within the composition. The question, then, is if people will use emoji to represent the layout of the image, rather than an action: Is it 🏰👨 or 👨🏰?

The results: Three-quarters of respondents selected 🏰👨 . But here’s the thing: Over half of people’s textual descriptions read the opposite way, where “man” preceded “castle.” The takeaway: Emoji aren’t just used as substitutes for words, following the grammatical sequence of a sentence —they can represent the ways things are physically arranged, too.

They’re “a way of orthographically representing spatial relationships,” Tatman added in a follow-up message. As in: “If you’re looking at a scene and there are two people in it who can be described using two different emoji, then you’re more likely to write the emoji so that the emoji on the right looks like the person on the right in the scene, and the emoji on the left looks like the person on the left,” she said. “You’re more likely to use emoji in an order that visually matches what you see in the scene.”

The first two images and the way they were emoji-described showed that depending on the composition of an image – like if there’s a clear agent and patient in the mix – people will deploy emoji in different ways. But what if those relationships aren’t as clear?

Enter photo three: A Man Photographing a Model.

So is this 👩📷👨 or 👨📷👩? This time, about 40 percent went with the former and 60 percent with the latter — a relatively even split. What jumped out to Tatman was how the emoji and sentence descriptions ran parallel to each other. If your sentence was “A man photographs a model,” then you’d be more likely to select 👨📷👩, but if it’s something like “Photo shoot by the water,” then you’d more likely go with 👩📷👨.

Taken together, the experiments show that emoji don’t have a “fixed syntax” like language does. “There’s so much free variation in how they get used,” Tatman explains. “They’re languagelike in some ways, but they don’t seem to be developing the type of robust emergent structure that we see in, for example, Nicaraguan Sign Language,” which developed spontaneously in the 1970s when deaf people from all around the Central American country were able to gather in large numbers for the first time.

With the exception of emoji like the pistol (🔫), where you have to point it at the thing being “shot,” she says that when you’re describing a scene like in these experiments, there’s likely no way to order emoji in a way that gives you an instant reaction of that can’t be right, like reading a sentence like “Picks girl cherries the.” In this way, emoji are kind of like paintings or music: never quite right or wrong, and (almost) always interpretable.