You may not remember Milo Yiannopoulos, the failed London tech entrepreneur who adopted a white-nationalist persona beloved by scores of 20-year-old white college bros convinced political correctness is the reason no one will sleep with them. If not, that’s understandable — his public visibility took a bit of a dive after he got banned from Twitter, in July, for sending the many Twitter-guppies who followed him around online after the actress Leslie Jones, leading to one of the worst and most famous Twitter-harassment incidents in the site’s history.

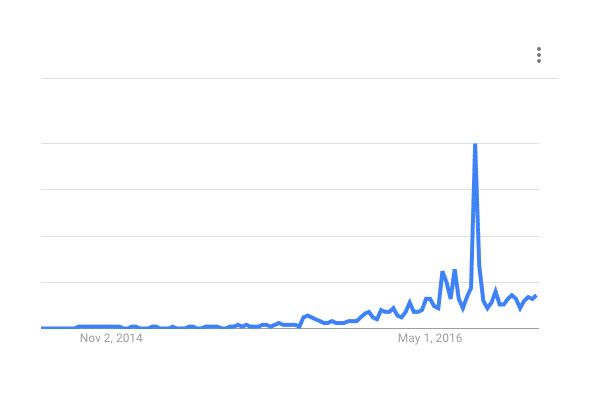

How big a dive? There’s a graph for that.

Let’s zoom out a bit:

What’s interesting is that, judged by different metrics, Yiannopoulos, who has a day job as Breitbart’s tech editor, has done well since his Twitter ban. He’s basically spent the period speaking to what appear to be good-sized college crowds, conducting stunts like bathing in pigs’ blood in Chelsea to make some sort of super-edgy and interesting point about Muslims (ISIS immediately disbanded), and getting written up for bizarrely credulous and glorifying profiles in Bloomberg Businessweek, and, much to the chagrin of the magazine’s readership given Yiannopoulos’s self-hating gay shtick, Out (in the former article, author Joel Stein printed, unchallenged, Yiannopoulos’s far-fetched claim that he has a staff of 30 he pays $1 million a year).

But at the end of the day, either people are searching for your name on Google or they aren’t, and undeniably, Yiannopoulos’s absence from Twitter has hurt his ability to build his brand. It’s an interesting data point, since the internet smart set likes to tell people that Twitter actually doesn’t drive much traffic, is terrible from an engagement standpoint, and so on. That’s true, but it’s also the best way to insert oneself into the ongoing daily conversation held by journalists (many of whom followed Yiannopoulos out of morbid fascination despite being disgusted by him) and the other people who devote disproportionate amounts of their lives to putzing around online. Without being on Twitter it’s really hard to stay visible to — please forgive me — influencers. There are just too many other distractions vying for their attention.

The above graph also ties into the perpetual argument over whether or not “don’t feed the trolls” is a reasonable approach to loathsome figures like Yiannopoulos. Now, this expression can mean at least a couple different things. As anti-online-abuse advocates rightly point out, “don’t feed the trolls” doesn’t work if you get dogpiled by thousands of Yiannopoulos’s sociopathic fans — it didn’t help Leslie Jones. In this sense, “don’t feed the trolls” is dumb advice.

But the line can also be applied to the many Twitter subcultures whose members hold that it’s always vitally important to call out offensive remarks, to hold them up to show people how awful they and the person uttering them are. Here, there could be some wisdom to starving the trolls. Yiannopoulos generates offensive remarks like Alex Jones generates conspiracy theories, and he benefited bigly, as his “daddy” might say, from having mastered the art of online shit-stirring and leveraging outraged reactions to his dumb opinions into yet more outrage and yet more shit-stirring. This was always his only chance at being interesting enough for normal people to pay attention to him, and now it’s mostly gone, because he’s lost access to the social-media platform that is most fueled by outrage.

This is one of those many occasions on which it’s appropriate to give The Simpsons the last word: