As a computer worm linked to hacking files and zero-day exploits collected by the National Security Agency continues to travel across the globe, it’s worth taking stock of how we got here — and what we can do to prevent the next attack. Unfortunately, as with so many things, it all comes down to Windows.

The ransomware — known as WannaCry, and apparently derived from an NSA-developed exploit called “Eternalblue” that was leaked earlier this year by a group known as the Shadow Brokers — encrypts whole computers, making their files inaccessible without a decryption key, which can only be acquired by paying up. It has, in this case, made medical files unavailable throughout England. And because it’s a worm, it spreads automatically from computer to computer, which explains why so many systems are going down at once.

The problem is not that Windows is particularly insecure — or, at least, it’s not just that Windows is particularly insecure. It’s that Windows is the most popular operating system in the world, and is generally the operating system of choice on most of the computers that people have at home, and oftentimes, at their place of work. It also powers the servers that many enterprise organizations rely on for emailing and file-sharing. The ubiquity of Windows has made it a prime malware target since personal computing exploded in the early ’90s (this also somewhat explains why there are far fewer viruses for Apple’s machines).

Luckily, it’s fairly easy to protect yourself. According to Ars Technica, you should be safe if you have the MS17-010 security update released two months ago — in other words, run, don’t walk, to your computer’s Settings menu and scan for software updates.

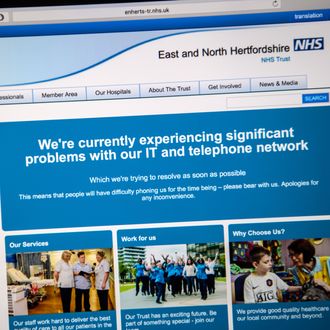

The bad news is that there are countless iterations of unpatched Windows installed on millions of computers around the globe. Much of this is tied to the OS’s use in big enterprise settings — like hospitals — where upgrading an entire fleet of machines is an involved process, much more difficult that upgrading one individual’s laptop. Many legacy systems rely on older versions of Windows — including the military. In 2015, the U.S. military was paying $9 million a year to use Windows XP. Windows XP. That same outdated system also powers Britain’s nuclear submarines. One could assume that Britain’s NHS computer network is hamstrung by the same technical limitations, that each node is an individual vulnerability, but cannot be patched on an individual basis.

Only a combined, concerted effort on the part of Microsoft, its major clients, and probably even governments to incentivize, push, prod, and in some cases even force all users to upgrade Windows will help head off more worms like this in the future. The problem with that is, well, governments tend to have an incentive to keep computers vulnerable to their exploits — this worm was built with NSA technology after all. So really, the only ways to fix this self-replicating problem is an effort to get everyone in the world to update their computer at once, which, yeah, it sounded stupid as soon as I typed it. Right now, the best you can do is make sure your own computer is upgraded. And hope your local hospital’s is, too.