Shopping experts Erica Cerulo and Claire Mazur, late of Of a Kind, and currently co-hosts of the podcast (and newsletter) A Thing or Two With Claire and Erica, will be regularly explaining how some of the out-of-plain-view parts of retail work.

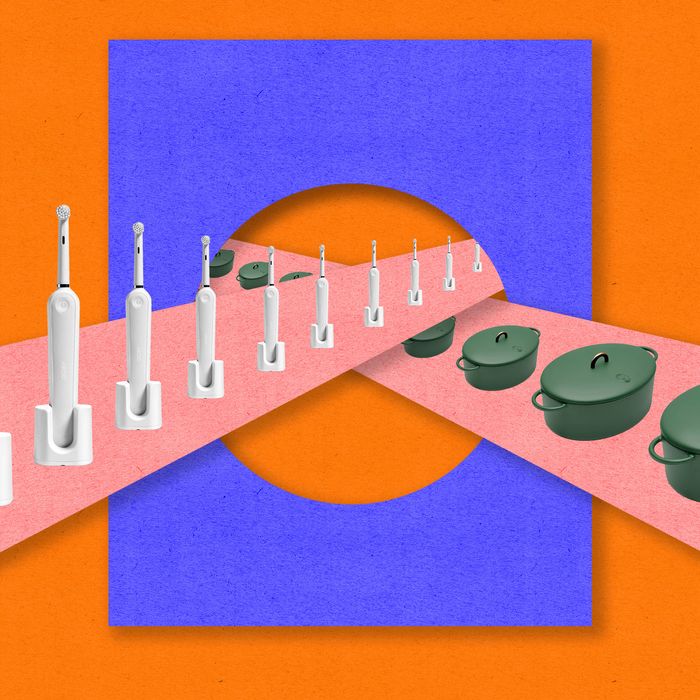

The Our Story page, which typically introduces founders’ aha moments and lays the groundwork for entrepreneurial mythmaking, is a familiar trope on direct-to-consumer companies’ websites. Fable shares the pet-first design philosophy behind its leashes and dog crates. A dozen pencil sketches of pots and pans sit above the text on the Great Jones’s version of the same. Scrolling through these neatly designed, carefully copy-written paragraphs and infographics, you get the sense that the existence of these companies is predicated upon their experience or expertise in making the thing they’re selling.

What these companies don’t include in their brand stories is something they, in fact, have in common: Their products were created with Doris Dev, an agency that handles product design, engineering, sourcing, manufacturing, and even fulfillment from its offices in Dumbo, Brooklyn, and Hong Kong. Since 2017, Doris Dev has become a getting-stuff-made ace in the hole — a firm that founders are often introduced to by early-stage VCs like Collaborative Fund and Lighthouse Ventures or creative studios like Red Antler when it’s time to turn their vision and enthusiasm (and funding) into an actual thing that comes in a custom, logo-stamped box.

The duo behind Doris Dev, Justin Seidenfeld and Lucas Lappe, met at Quirky, which brings individual inventor’s ideas to life and was, during their time there, “this amazing place where we spent way too much money and learned how to make a lot of products really quickly,” as Lappe puts it. They both eventually left for brands focused on highly specific product categories — Justin to Raden suitcases and Lucas to Goby toothbrushes — and quickly realized there was an opportunity to do for many brands what they’d each been doing for one. They’d take care of the physical product and let the founding teams — which typically had backgrounds in marketing and/or operations — tackle the rest. Nearly four years later, they’ve become the soup-to-nuts solution: “Start-ups come to us and say, ‘Hey, we want to launch this thing,’ and we can basically lead all the work from ideation through shipping out the physical product to their customers,” Seidenfeld says. “They only need to then focus on building out and toning branding muscles, their marketing chops, their distribution footprint, and we can focus on all the backend.” Essentially, companies need to figure out how to sell the product, while Doris Dev tackles what exactly they’re selling.

Plenty of aspirant category disruptors — looking to produce, say, a heavyweight blanket or a lightweight stroller — have taken them up on this proposition, including By Humankind, Lalo, Loftie, Loveseen, and Gravity. Which makes good sense: Manufacturing is a closed, stodgy network, and even people with industry experience and know-how typically end up needing intermediaries of some sort to help them figure out how to actually work with a factory versus just finding one.

But Doris Dev’s value to companies extends beyond factory know-how. For certain product categories, producing something independently would mean building or buying a production facility — not something a founder does with a $3 million seed-round investment. And for nearly all product categories, independent manufacturing would slow the process by years, not months. Depending on the product in question, there are also testing and compliance hurdles to contend with. See: the story of Bobbie, an infant-formula company that was hit with an FDA recall before teaming up with Perrigo, one of the main formula manufacturers in the U.S. Often, partnerships like this allow a company to tap into supply chains that are already in place and potentially underutilized. Much of this is positive. Doris Dev clears a path for founders, taking on the managerial load of product development (a huge plus for the many first-time entrepreneurs with minimal experience managing a team) and enabling more types of entrepreneurs and more types of products to go to market. Got an idea for a game-changing breast pump but no experience in engineering? Don’t let that stop you from bringing something to life that might fundamentally change the experience of new parenthood. Other new parents who are also cursing their breast pumps are served in the process.

This outsourced model is hardly original to the DTC start-up boom, even if the earlier versions weren’t as all-under-one-roof as Doris Dev or the San Francisco–based Box Clever, which has partnered with the luggage mainstay Away, the cookware line Caraway, and the minimalist A/C company July. “There have always been industrial-design studios — that’s been around since effectively the turn of the century,” says Lappe. And contract manufacturing has been booming since the Space Age, with NASA and IBM early to the game. What is new is consumers’ expectation of visibility into the process of how things are made, who’s making them, and where the materials are coming from — which is where the prevalence of this model starts to raise eyebrows. If the people inside a company aren’t sourcing the materials or selecting the factories themselves, they’re relying on others to vet them. And these others, well, do they care about the things we want them to care about? How plugged into the business are they anyway? If they don’t have a direct relationship to the people or places physically making the products, do we trust them to reflect the brand ethos we were promised in Instagram posts and on About pages? Following the publication of an Insider piece about the leadership failings of Great Jones, the Defector published a follow-up that zeroed in on what many perceived to be the real scandal: the company’s shockingly tiny team that felt incongruous with brand’s omnipresence on the internet. “Great Jones, further proof that every company is a streetwear brand, outsourcing design / manufacturing / creativity and then just doing drops over Instagram,” tweeted design writer Kyle Chayka.

And there can be other drawbacks to taking this route, too. Without the right oversight, there can be quality issues — the contrast between what you bought on Instagram and the product that showed up at your door is practically a meme at this point. Plus, even if the quality holds up, outsourcing the entire production chain can mean that the product is, materially, not that different from most others in its category. The Away suitcase, for instance, was — per the founder of the agency Combo, Kapono Chung, who designed its first iteration when he worked there — “manufactured at the same factory that all of these other suitcase brands are manufactured at. The manufacturing company is great — they’re a solid company. But [Away’s team was] really heavily focused on brand — telling the story rather than getting the product to be this amazing product.”

Plus, there’s the simple fact that outsourcing like this doesn’t square with the radically transparent ethos we’ve come to expect from direct-to-consumer brands. And though none of the companies that use Doris Dev are exactly hiding it — the information is available to anyone capable of a quick Google search — they’re not going out of their way to let people know, either. Doris Dev isn’t name-checked on Fable’s pink-and-green About Us page (“Everyone has a story. This is ours,” it reads); Great Jones doesn’t tend to talk about them at panels.

Of course, there’s more than one way to bring a product to market, even if the world of venture capital — one of the few forms of funding available to burgeoning start-ups — seems to prefer a one-size-fits-all approach. For companies that do opt to keep their manufacturing in-house, by-products like limited inventory that often sells out and a DIY production ethos can be valuable brand distinctions in an otherwise crowded and homogenous market. The millennial-favorite dishware company East Fork — up against venture-backed, factory-manufactured competitors like Our Place and Year and Day — gets straight to the point on their About page: “East Fork designs, manufactures, and sells thoughtful, durable ceramic dishware in Asheville, North Carolina. Trained in formal ceramic apprenticeships, our founders’ hands spent thousands of hours in clay, making hundreds of the same form at a time and building an intimate familiarity between maker and material.” In other words, part of the sell is that they get their hands dirty.

The Strategist is designed to surface the most useful, expert recommendations for things to buy across the vast e-commerce landscape. Some of our latest conquests include the best acne treatments, rolling luggage, pillows for side sleepers, natural anxiety remedies, and bath towels. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change.