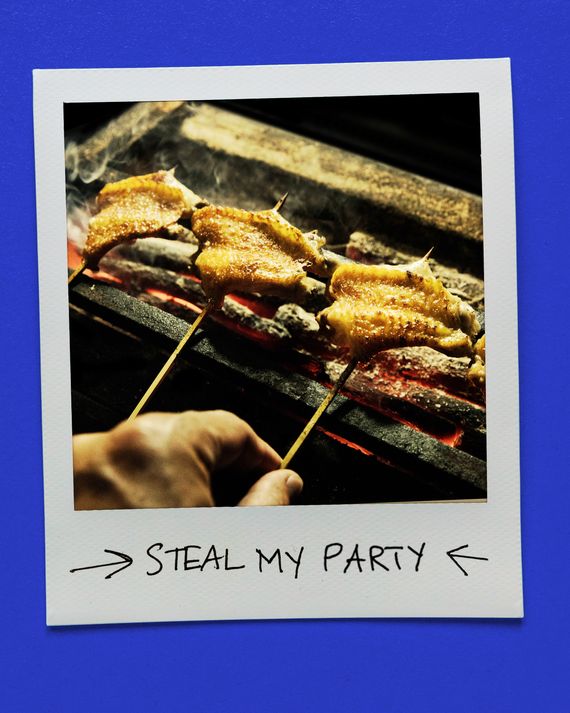

Hosting can be a lot, especially when part of the game is having the soirée you put together look effortless. In this series, veteran party-throwers tell us how they pull off their highly specific, flawlessly executed gatherings (well beyond the holidays). This installment comes from Dylan James Ho, a Los Angeles–based photographer who went from eating yakitori in Japan, to grilling it himself at home, to starting a professional pop-up. Here, he shares how he hosts a casual evening filled with friends and skewers.

In December 2019, photographer Dylan James Ho bought a two-person shichirin — a small charcoal grill — at a kitchen-supply store in Tokyo called Kama Asa. He carried it by hand back to Los Angeles and began making yakitori in his backyard. Ho’s yakitori obsession was born in Japan, where he had traveled to as much as twice a year over the course of the previous decade. (He even studied Japanese to be able to better read yakitori menus.) But it wasn’t until the pandemic hit that he took his observational knowledge and “really hit the gas on this at home,” he says.

He read cookbooks and watched hundreds of YouTube videos. He bought whole chickens and broke them down himself. He invested in a bigger shichirin, and then a bigger one, and then a bigger one. As pandemic rules eased, he began to have friends over outside to share the meal, and after a few sessions, they encouraged him to start a pop-up. So earlier this summer, Ho launched Tori! Tory! Toré!, organizing dinners for clients in their own spaces.

But when Ho isn’t cooking yakitori professionally, he still loves to have friends over in a relatively casual manner. His preferred method, which he details below, is interactive. Guests sip on wine (and beer and sake) as they thread chicken parts and seasonal vegetables onto bamboo sticks. Then, everyone proceeds to the backyard. (“I like to promote moving around,” he says. “You’re not confined to your seat.”) Meanwhile, Ho takes to the grill, seasoning, flipping, and handing out skewers as he goes.

One day before: Grocery shopping

The afternoon before, I grocery-shop, either at the farmer’s market (Hollywood, Santa Monica, and South Pasadena) or a good store, like Tokyo Central Market, Marukai, Mitsuwa, and H Mart. D’Artagnan is a great place to shop online for premium, farm-raised chicken. I always do a mix of chicken parts: thighs, tenders (the inside of the breast), wings (both the flats and drumettes), maybe some organ meats (hearts, gizzards, and liver). If your butcher carries schmaltz, you could pick some up to use as the cooking fat for the veggies — it’s not strictly necessary, but it makes them so delicious. And then I love shiitake mushrooms and a mix of other vegetables, whatever is in season: zucchini and eggplant, okra, snap peas, corn, and little yellow or purple potatoes are crowd favorites, but you could do Romanesco or broccoli — I’ve even seen grilled tomatoes.

The general rule is that you want about ten skewers per guest, a mix of each kind (more on how exactly you’ll be building those skewers below). I’d get a little extra of the stuff you think people are really going to like, such as wings and thighs.

Beyond the meat and produce, I make sure I’m stocked up on the condiments I need for serving: yuzu kosho and Japanese seven-pepper spice, which includes dried chile peppers, crushed seaweed, and sesame seeds. Those are the two things I set out for guests to use themselves; otherwise, I’m handling any added flavors or ingredients as I grill.

I also buy some bottles of wine. I particularly like oranges and whites with yakitori. Especially in summer, the juicier, the better, like the Meinklang above. For some reason, yakitori and red wine doesn’t really taste good to me. I also know my friends will bring beer and sake. But you can drink whatever you like with it— whatever makes you happy.

That evening, I make tare — a mix of soy sauce, mirin, sake, and sugar — which is the finishing sauce for certain skewers and one of two basic seasonings for yakitori (the other is good sea salt, which you use on the front end of the cooking process). Tare needs some time to reduce, simmered over low heat in a saucepan. It takes about an hour and a half or so to make a good quantity.

Day of

12 p.m.: Prep your ingredients

In the afternoon, I prep the meat by cutting any chicken parts into bite-size pieces and washing the vegetables.

4 p.m.: Set up the table

I put the yakitori grill in the middle of the table so it’s ready to go (the model I own is out of stock, but I’ve heard good things about Bincho and Yak). Then I set out some small plates and glassware, along with the yuzu kosho and seven-pepper spice.

5 p.m.: Friends arrive

Everyone is going to help skewer. You can technically use any wooden skewer, but I like the flatter, wider ones because there’s no chance they’ll roll or rotate on their own on the grill.

First, I make sure guests have a drink and then I put them to work. I set up stations around my dining table or the kitchen island. People thread different types of skewers, and they all end up on one giant platter (or you could use a disposable tinfoil baking tray or a sheet pan) so they can be easily carried outside later. I keep the meat on one side and the vegetables on the other.

I’ve done mushroom medleys with four types of mushrooms on one skewer, but that’s just me being fancy. Or there’s a popular one called negima (ねぎま), which is chicken thigh and green onion. But I usually do one ingredient per skewer, as they tend to in Japan.

Every skewer will be about 35 to 50 grams. You want to fill it with three or four bites only, which is no more than four inches of food per skewer. Another key is to not show too much of the tip. The Japanese feel that it doesn’t look pleasant, and some people aren’t careful and will jab the insides of their mouths. So putting the food close to the top is important, as is making sure there’s no space between the pieces by stacking them tightly.

A lot of people assume you need to soak skewers before, but that’s a Western way of thinking. The reason is because most people grill on a giant Weber and they put the skewer in the middle, where it’s so hot that the skewer gets incinerated. With the yakitori grill, the majority of the stick extends out so it’s not directly over the coals. That’s another reason to have the food close to the top: That way, the tip doesn’t burn off.

6 p.m.: Start the coals

The skewering process will take about an hour to an hour and half, so I sneak out at 6 p.m. to start the coals. Binchotan is the charcoal the Japanese traditionally use. As opposed to American briquettes, which are little lumps, these are longer, more rectangular blocks. But you start them in a chimney, same as you would for any charcoal grill. Light them up and just walk away. It takes about 45 minutes to get to the right heat level.

When they’re ready to go, you’ll stack the charcoal up inside the grill like Tetris, pretty close to the top without protruding. You use a pair of tongs to move the hot charcoal around and fit it into place. If you can only get regular briquettes, that’s fine. Your heat just won’t be as even.

When the coals are getting hot and the skewering is finishing up, I set up my toolbox, which will also come outside for cooking. The basic list of what you need is the tare; a spray bottle with sake (whatever kind you like to drink, with a strip of kelp added for umami); a spray bottle with shoyu; some good sea salt, as I mentioned earlier (a salt shaker helps the application process); and a brush (you can use a Japanese brush or a silicone one). For my more advanced setup, I also include a couple of pairs of small tongs to maneuver things around, scissors and a utility knife (in case I need to trim, cut, or check doneness), a hammer for breaking up the coals and releasing more heat once they start to cool down, and a bar-gunk scraper, which I use to clean the particular type of grills I have.

7 p.m.: Grill time

When the grill is ready to go, everybody pours more drinks and moves outside. (I also always make sure there’s a wine bucket to keep bottles cold.) I bring out the tray of prepped skewers, all my cooking materials and tools, and a clean tray for the finished skewers so they have somewhere to go, even if people eat them pretty immediately. Those all go on the table with the grill. As people are mingling, I get going. Like I said, I always cook the veggies with schmaltz, which I think is key in terms of taste and also adds a nice sheen. But you could use olive oil or a 50-50 blend. You’re brushing the fat on the veggies, sprinkling them with the salt, and then putting the skewer down on the grate. Then you grill, flipping every couple of minutes, until there’s a nice doneness. The chicken will generally be a bit longer, the vegetables a bit shorter. But in both cases, you want the outside to be browned but not burned.

For the meat, I spritz all the pieces with cooking sake, which I keep decanted in a houseplant spray bottle. The reason is flavor, but it’s also a fire retardant. It buys me more time. Sometimes, I also spritz shoyu, if I want that flavor. Then it also gets sea salt.

From there, the flavor combinations are really up to you. The tare can be brushed on towards the end of cooking on both sides, whether meat or veg. It adds flavor, of course, but also a nice color. Some combinations I really like are okra with katsuobushi (shaved bonito flakes), zucchini with Pecorino Romano grated on top (this is actually a Japanese thing), eggplant with miso paste (なす味噌 nasu miso), and chicken hearts and gizzards with tare. I could go on, but if you want more flavor inspiration, I recommend Chicken and Charcoal and Chicken Genius — or you can watch some of my Instagram highlights to see what I’ve done in the past.

As the skewers finish, I place them on the clean platter — though they don’t last long. People come up and grab them and eat them as I go. It’s a charcoal grill, and depending on its size, you’re only going to be able to fit so many at a time. The whole thing should take two and a half or three hours. But it’s a dinner party — you have to be patient with the process.

The binchotan burns hot for a long time, so at the end of the night, the way to fully extinguish it is to soak the pieces in water for a few minutes, then set them on a sheet tray outside and let them sun-dry the next day. If you do that, you can actually reuse them. As for the aftermath, all the yakitori parties are always quite a mess. When you wake up the next day, in case you forgot what happened the night before, you’ll be reminded of the debauchery. There are skewers everywhere, and you’ll smell that chicken still. It smells great, that aroma. If you don’t take a shower, you’re gonna reek of chicken, which is the story of my life.

The Strategist is designed to surface the most useful, expert recommendations for things to buy across the vast e-commerce landscape. Some of our latest conquests include the best acne treatments, rolling luggage, pillows for side sleepers, natural anxiety remedies, and bath towels. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change.