I should be honest: I couldn’t watch Here Comes Honey Boo Boo. After fifteen minutes of Go Go Juice and pageant tantrums, I had to turn it off — not because I disapproved of the Thompson-Shannon family, but because I resented that the show wanted me to disapprove of them. It’s the same way I feel when I watch Toddlers and Tiaras, where hyperprojecting mothers bitch-slap sequins onto eager-to-please daughters, inviting the viewer to wonder, What train wreck of adulthood lies ahead for America’s Honey Boo Boos?

I arrive at this question a little defensively because I am myself the alumna of one child pageant: I placed second runner-up in Miss Preteen Minneapolis 1996. And no feminist is more agog than I am to report that my pageant experience was generally positive. (Of course, this may be informed by the fact that I placed.) But was I the norm or the anomaly? To find out, I interviewed adult alumnae of child pageants about how they feel about it in retrospect — and reconsidered my own experience.

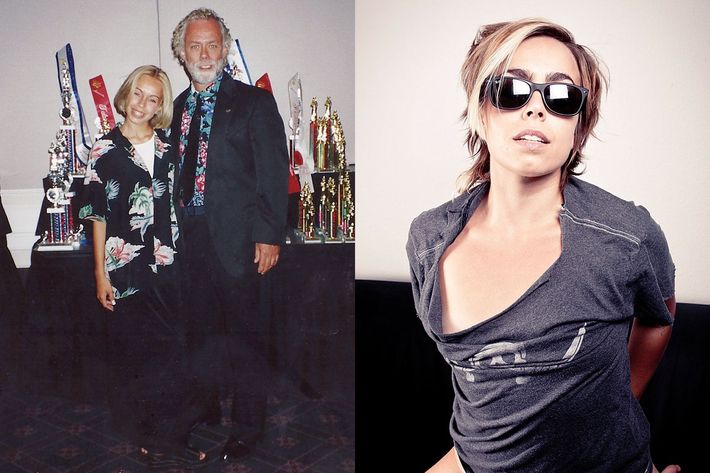

1. Marly Ramstad, 28, designer in St. Petersburg, Florida

American Coed Pageants, 1998, age 14: Miss Teen Photogenic, Best Personality.

I got a brochure in the mail and was like, Oh, this looks like fun. At the time, I was super-anorexic. I probably weighed, like, 90 pounds. All I remember that summer was eating tomatoes. Looking back, doing the pageant was a self-esteem thing — I wanted so badly to be pretty and perfect that if I won, then that would confirm my perfect figure, perfect weight. At the time, though, it just felt like something fun to do. I love pretty dresses; I went to prom like nine times when I was in high school.

So I’d never done a pageant before, and the girl next to me — I was Marly Ramstad, and she was Mindy Rick — Mindy Rick had done the American Coed Pageant since she was, like, young enough to do it, for-fucking-ever. She was the pageant queen. And to me, she was all like, “Well, Marly, I just don’t think you know how to do the walk. Let me teach you the walk.” She bugged me so bad, but I was thankful for her. She knew everything. And Mindy Rick, like, swept the competition. She had, like, a fucking bridal dress on.

She won the all-around, the most promising model, the talent, the speech category. But the only awards she didn’t win were the ones I took from her. Miss Photogenic. And I always befriended the awkward girls, and those girls voted for Best Personality. There were a lot of really fabulous black girls. It was probably half black girls, then a quarter suburban white girls, and then super-podunk back-country girls. Those were the girls who won, like, Best Community Leadership and volunteer awards. There was a whole group of black girls who did the competition together, like as a community, and we would party, have so much fun.

2. Robbie Meshell, 27, hairstylist and makeup artist in Shreveport, Louisiana

100-plus pageants from ages 3 to 7 and 14 to 27, including Miss Louisiana Elite USA 2011.

I’ve done over 100 pageants. I did them from 3 to 7 years old, then stopped. My mother passed away when I was 10, and that’s who I did my pageants with, because of course Dad’s not going to. But I love it. I love everything about pageantry. I started again at 14, and I’ve done at least one a year, up until last year.

When I was 10, my mother committed suicide, so my platform was suicide awareness. I wanted to tell my story. After my mother committed suicide, I was very antisocial. Getting into the pageant world brought me out of that shell. It allowed me to tell my part of the story, the child’s side of what happens when a parent commits suicide, and the more I talked about it, the better I felt. I just enjoyed — I know that sounds very odd — but I enjoyed interviewing and telling my story and speaking about suicide awareness. It lifted the weight off my shoulders.

My mother participated in one pageant that I know of. She was the Farm Bureau Queen in 1976. I was Farm Bureau Queen in 2006.

We Louisianans take our pageants very seriously. I know this because I now do hair and makeup for pageants for all ages. It’s like a sport. You practice every week — you eat, sleep, and breathe pageantry. From the makeup to the dress to the spray tan, you’re in it to win it. Louisiana takes it very seriously. The moms want it as much as the daughters.

3. Tamara Tobin, 29, student in Colchester, Vermont

Fifteen pageant titles from ages 7 to 16, including Miss Vermont Junior Queen and Miss Autumn Fest. Now a pageant mom.

I was really, really shy growing up, especially at the age of 7, but I ended up first runner-up at my first pageant and Miss Hospitality at my second. I was excited because I got a crown and sash, and wanted to keep going. My mom was never one of those crazy pageant moms that you see on TV, that has to pump me with Mountain Dew. The biggest thing for my mom was getting me out of my shyness. When I won Miss Vermont in ‘94, my whole family got to go to Florida.

Now that I have two little ones, a 5-year-old and a 2-year-old — my oldest just won a title last month, and we’re doing another with the youngest this month. I think, in general, the Northeast is a different pageant system. They don’t rely so much on flippers [children’s dentures to replace missing teeth] and all that stuff. There will be some spray-tanning here, but it’s very minimal. There are hair extensions, but it’s more of a natural glitz than a complete glammed-over glitz. Of course, me growing up in the pageant system, my daughter’s dress is very glitzy. Do I put makeup on her? Yes. But I don’t think I overdo it for a 5-year-old. I was so proud of her when she won this last pageant — it was a whole another sense of, like, when your kid takes their first steps or they roll over for the first time. I was just so giddy and happy and so proud of her, and I started crying a little bit.

4. Crystal Brown-Tatum, 41, owner of Crystal Clear Communications in Dallas, Texas

Miss San Antonio Teen 1987, seven adult titles including Miss Texas 1990, Mrs. Black Louisiana 2012. Now a pageant mom.

I never thought a black woman could win a pageant until Vanessa Williams won the Miss America pageant. Seeing her crowned Miss America, I decided to compete in my first pageant. I was always the girl at school that was the only black cheerleader or the only black girl in Gifted and Talented, and so my perception of beauty — it wasn’t me. I never thought I was pretty because everyone who was popular and pretty was white. Vanessa Williams changed the course of my life.

My father was in the hospital. He had been accidentally shot and was quadriplegic. But pageants were always on TV, and he watched TV all the time in the VA hospital. So that’s what kind of motivated me — a desire for my dad to see me on TV. My mom and I had a rocky mother-daughter relationship, but when it was pageant time, she took pride in helping me select a gown and work on my talent. What motivated me was making my parents proud.

I gave up pageants to have my daughter Jaclyn, and a lot of people were trying to persuade me to terminate my pregnancy so I could still compete, and although my own personal views are pro-choice, for me, at that time in my life, I wanted to have her. Now she does pageants. She had a very bad experience with the Miss Louisiana teen pageant. We both felt that it was rigged. So when we heard about the Miss Black Louisiana teen pageant — Jaclyn is biracial, but she considers herself black — we felt she’d have a better opportunity. And sure enough, she won. When I was doing the paperwork, they had a Mrs. category, and I was like, “Oh, wouldn’t that be funny if I entered?” and she was like, “I dare you!” [Crystal is now Mrs. Black Louisiana.]

Black pageants don’t raise the big dollars like the mainstream pageants. But in my opinion, the black pageant circuit gives girls opportunities who would never make it in the mainstream based on their body type, their talent, the funds they raise. It was $150 for Jaclyn and I each to compete in the Miss Black Louisiana system. When she competed at Miss Louisiana Teen, it was $750. That’s a lot of money.

I judged a pageant this summer, and one of the contestants is like a celebrity here because she was on Toddlers and Tiaras. She was a lovely girl, but her wardrobe was horrific. For her to be 13? She looked like a prostitute. All of the judges were horrified. I’ve seen moms cuss judges out; I’ve seen moms take out second mortgages on their homes to buy gowns. People were living in trailer parks but spending thousands on pageants. Even I made a part-time job coaching girls for $25 an hour, which is such a high wage in Louisiana. The average household income is $21,000, yet people spend all this money on pageants.

Honestly, I think a lot of the moms live vicariously through their daughters. Being in a small town, when you’re a queen, that’s an honor. You get to ride in a parade, you make the front of your local newspaper — it’s a way to buy your child celebrity status in the South.

5. Heidi Gerkin, 36, stay-at-home mom and former news anchor in Shreveport, Louisiana

Miss Sunburst Petite, Ohio Junior Miss, America’s Junior Miss, three-time top-five Miss Ohio competitor.

The first pageant I did at age 7 was called Miss Dixie Darling, which is part of a system based out of Nashville. I did beauty, photogenic, sportswear, talent — I won all my divisions my first time out, which of course kind of gets the hook in you.

I remember my mother was smoking backstage once — this was the eighties, so people could smoke wherever they wanted to smoke — and another mother went off on her because her daughter’s dress was flammable. What kind of person puts their kid in a dress that they know is flammable?

More than anything, pageants shaped my relationships with women. Most of my close relationships have been with men. That sounds really bad, but in the world of pageants, you might perceive someone as your friend, and then they seek out weaknesses and turn that around on you. You never knew who was really your friend. The other girls didn’t like me. They spread rumors that were never true. I always wondered why they didn’t like me — was it just because I was successful, or was I actually not worthy of being liked? Even now, whenever I meet somebody, I question whether they really like me.

I’m extremely critical of myself, probably more so than the average person is. I have really high, sometimes unrealistic expectations, and I think a lot of that comes from pageants. I remember a pageant where I wore my hair up, and I won the pageant, but afterward a judge said, “Don’t ever wear your hair up again, your ears stick out.” And to this day, I’m uncomfortable wearing my hair up.

I had a career as a news anchor, and a lot of the same image stuff, the competitive stuff, the girl stuff, goes on. But one thing that pageants did give me was a tough skin — you can’t work in news media and have a thin skin. You’re constantly criticized by your viewers, by your co-workers, by your employers. It’s a lot like pageants, actually. It’s common in both fields to get e-mails from strangers saying, “Your hair looks like shit today.” So pageants did prepare me for real life, because let’s be honest, the real world is not a nice place. There’s a lot of mean in the world.

6. Laura Goode, 29, writer in San Francisco, California

Miss Preteen Minneapolis second runner-up, 1996.

Before setting out to find and interview subjects for this article, probably ten people in my life knew about Miss Preteen Minneapolis. My most salient memory from the experience — other than the forest-green Dyeable pumps that matched my forest-green velvet-and-taffeta dress — is the pageant director teaching me how to give a firm handshake.

Recently, I visited a college class my friend teaches on critical thinking. “What assumptions would you make about me if I told you I was Miss Preteen Minneapolis 1996?” I asked. (I often abbreviate the story this way, which is, of course, telling. A Google search reveals that the actual Miss Preteen Minneapolis 1996 grew up to be a model. She appears on the covers of romance novels and in at least one Fruit of the Loom underwear campaign.) After being reassured that I wouldn’t be offended by anything they said, the all-female class told me I was vain, conceited, stuck up, full of myself — they couldn’t possibly have found more derisive ways to say, “You know you’re pretty” — stupid, trashy, and probably a bitch.

“Okay,” I said, struggling to make good on my promise not to be offended. “What assumptions would you make about me if I told you I had two degrees from Columbia University?” All of a sudden I was smart, ambitious, successful, high-achieving, and rich. The only common descriptor to the two prompts was “stuck up.”

We can opt out of pageants, but we’re still stuck with the double blind in which America entraps all competitive, consciously sexual women: female competitions are a loser’s game because you’re ugly if you lose, and shameless if you win. Between the women who told their stories here and the pageants, judges, and titleholders I spoke to in the process of finding them, two narratives emerged: We competed in pageants because we (and our mothers) wanted to win. But we resist talking about it with outsiders, lest they mistake us for something we’re not. We share the pride and humiliation at competitive femininity—or perhaps just competitiveness itself.