“I’ve been developing a repertoire,” my friend Anne recently told me. She was dating actively for the first time after a difficult breakup, the kind that casts doubt on everything you thought you knew about your romantic abilities and desires. What kind of partner did she want? What kind was she capable of having? Did she want a partner, at all? Could she handle one, yet? As Anne reentered the dating scene, she found herself dating a wider variety of men than she’d dated before — and neither rejecting nor committing to any of the prospects.

There was the hard-partying man she drank with until dawn. The intellectual man she conversed with until dawn. The practical man with whom she discussed finances and her career. And the man with a bad sense of humor with whom she had nothing in common — other than their interests in bed. (In 30 Rock’s brutal parlance, he might be the “sex idiot.”) Repertoire-maintenance was simultaneously exhausting and thrilling, she reported. Text-messaging aided in the maintenance of multiple ongoing flirtations, of course. But as scheduling regular face time (as opposed to FaceTime) with each option began to wear her down, still she found herself unable to choose just one.

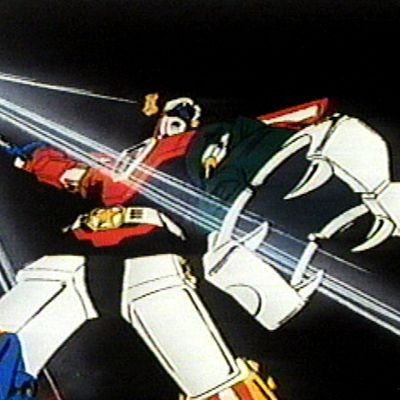

“If only you could combine them all into one Voltron boyfriend,” I sighed, thinking of the 1980s cartoon Voltron: Defender of the Universe, about a team of warrior robots that would assemble themselves into one giant, unstoppable super-robot to defeat their foes. The yellow robot, piloted by a strong man named Hunk, became the left leg; the green robot, piloted by a brainiac named Pidge, became the left arm; and so on. And so began what Anne and I now refer to as the Voltron Theory of Casual Dating: In the absence of one good partner, an actively dating single person will naturally construct a corpus of complementary partners who, if assembled into one giant Voltron partner, would be his or her ideal boyfriend or girlfriend. (Much like the Wu-Tang Clan.) Occasionally, the Voltron becomes so attractive that it eclipses the appeal of any one person. This shift marks either the downfall of dating, or the beautiful escape from infuriating gender roles and frustrating pressures to nail down a spouse.

You won’t necessarily set out to do it. You may not even date all the components of your Voltron at once. But dating is, at times, a reactionary enterprise — after finding a deficit in one romantic prospect, you react by seeking his foil as a sort of counterpoint. These assemblages are, at times, practical: Guy A doesn’t like parties, but you need a date for an upcoming one, so you find Guy B. But they can also be revelatory: You ignore Guy B and spend the night texting Guy A; perhaps party attendance isn’t as essential as you thought. Or perhaps you discover that neither man, on his own, is good enough — but now that you’ve seen which qualities were essential, and which were superfluous, you know what you’re looking for next. You’re testing out options and figuring out what you want at the same time. For some, this process is excruciating — anxiety-inducing, energy-sapping, time-wasting. But as traditional pressures to couple off continue to diminish (half of Americans believe society is “just as well off” when marriage is not a top priority) the romantic permutations available to a person are not limited merely to “coupled” and “single.” A truly single life, with minimal dating, is very different than single-but-dating-a-lot. For most people, the latter is a temporary state when fluctuating between coupled and single life. But for the most socially hardy among us, the Voltron can continue for years.

“That is the only thing that ever works for me,” my friend Juliet said of her long-term romantic prospects when I told her about the Voltron theory. “Take the professor,” she says of a long-running paramour she’d nicknamed for his bookish mien. “He hates rap, but I like how he dresses, and his taste level in terms of, like, casually taking me to the Chateau Marmont and Rudyard Kipling’s estate in Vermont. He fulfills a sort of snobbish part of me, watching Brideshead Revisited and such.” Meanwhile, another love interest offers “aggressive sex.” She describes a third man’s primary attribute as his perpetual availability. “He’s the attentive one,” I offer. “I just call him when I’m desperate,” she replies.

(Speaking of booty calls, it is perhaps worth noting that Hunk was not the romantic lead of his Voltron team. That was Keith, the levelheaded nice guy. Hunk was the sex idiot.)

There was a time when a man who assembled his love life this way would be considered an “incorrigible bachelor.” But absent a central monogamous commitment, even those who fully expect to end up in a traditional marriage live in a sort of unspoken state of casual polyamory. Until exclusivity is established, casual daters are generally assumed to be sleeping with — or at least flirting with — any number of people, any number of levels of seriousness. Juliet sees some members of her Voltron regularly; others only a few times each year. Anne has one date with whom she discusses other dates; the others know not to expect exclusivity, but don’t know much else. Unlike the robot Voltron, the components of your Voltron Boyfriend don’t know who the other components are, or what they’re adding up to — which is often the source of problems. “I thought you were sleeping with other guys the whole time,” a man once said after dumping me. “No, only you, I just hadn’t told you yet,” I cried. By then, though, the stress of the unknown had already animated too many fights. We called it off and moved on.

The Voltron exists both as a release from commitment and, oddly enough, in deference to it. As I’ve aged I have found myself, paradoxically, less willing to commit to anyone. Commitment now is more meaningful than it was in my early 20s. A serious relationship then could last for years, and still be disassembled with plenty of time to find a new mate — or multiple new mates — before I even started to think about marrying or children. Now that I’m 30 and both are tangible possibilities, committing is more significant — which means I’m less willing to do it if I’m anything less than completely certain. The Voltron releases any one relationship from that kind of pressure, allowing each to exist on its own terms. “And it’s about viewing dating as a multifaceted experience as opposed to a goal-oriented game about getting married,” Anne noted. “Which is really freeing.”

Every day, it seems, a female writer will publish a new essay about her struggle to find one appropriate, commitment-ready mate: “There’s something wrong with the men of your generation,” Jillian Dunham’s fertility doctor told her. “I want to have a baby on my own,” Alyssa Shelasky realized with a start when she saw that her love life didn’t match her reproductive goals. The dilemma is, in part, demographic: Women today are more educated than men, but close to one third of them still want partners with equal or superior educational achievements. Heterosexual women tend to find men their own age attractive; heterosexual men have an alarmingly consistent attraction to 21-year-olds. “Maybe it’s one of those End of Men things,” Anne mused once over brunch, citing Hanna Rosin’s lightning-rod book about female success and the decay of traditional gender roles. As she listed the eligible single women we know who, despite trying, never seem to find commitment-ready mates, Anne argued that perhaps the solution is to turn those men’s commitment-phobia back against them — and to reinvent your love life on your own defiantly selfish terms. Anne has become so enamored with her Voltron of late, that she’s begun to imagine a life without a central commitment, ever. “I suppose that’s when the Voltron gets a bit subversive,” she said, “when you do it because you just like it better.”