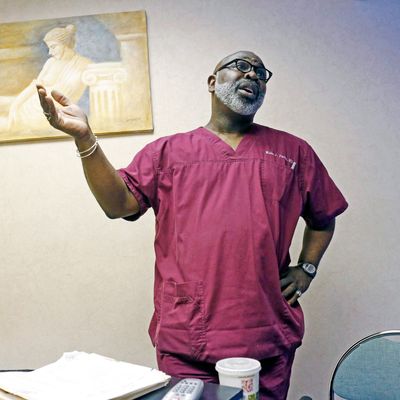

When Dr. Willie Parker speaks, it’s with a preacher-like cadence honed from years attending the First United Missionary Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama — and years soothing women whose pregnancies he’s about to end. Parker, one of the most prominent abortion doctors in the South, has spent years living on the road, traveling a circuit between southern clinics thousands of miles apart. And all that time, he’s been a devout Christian.

There’s no doubt that Parker is, as he puts it in his memoir, Life’s Work: A Moral Argument For Choice, which was published this month, “as rare as snow in July” — he’s a Christian, African-American abortion doctor practicing in the Deep South. But although some might see him as a paradox, Parker considers performing abortions for women in need to be a moral obligation. “The Scripture came alive and it spoke to me,” he explains in the book (which was ghostwritten by New York’s Lisa Miller). “For the Samaritan, the person in need was a fallen traveler. For me, it was a pregnant woman. The earth spun, and with it, this question turned on its head. It became not: Is it right for me, as a Christian, to perform abortions? But rather: Is it right for me, as a Christian, to refuse to do them?”

His memoir tells the story not only of his conversion, but of his childhood in rural Alabama, his journey out of poverty through college and then medical school, and his early career as an obstetrician — but one who refused to perform abortions, which he saw as morally wrong. When a chief administrator at a clinic where he worked banned abortions completely in 2002, however, his whole perspective changed. Although he’d never been adamantly against abortion, he realized that he was failing to act on his Christian principles if he did not actively help women in need. To him, a clump of cells is no more sacred than a woman’s agency. “If God is in everything, and everyone,” he writes, “then God is as much in the woman making a decision to terminate a pregnancy as in her Bible.”

After this revelation, Parker began training full-time in abortion care. Since then he’s performed thousands of abortions, and his profession combined with his faith has made him one of the most vilified figures of the Christian right. Ahead of his book launch at the New York Society of Ethical Culture in New York, Parker sat down with the Cut to parse the anti-abortion movement’s next move, the Christian right’s political outlook, and that bizarre Mike Pence quote.

To start, you said you were on the steps of the Supreme Court when it ruled, in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, that Texas lawmakers’ regulations of abortion clinics violated the Constitution. How do you think that ruling will affect the anti-abortion movement?

I think initially the antis were a little disheartened because they weren’t going have a legal precedent to embolden them. What they’ve relied on as a strategy — the hyperregulation of abortion — they lost. But I think they’ll find new ways to undermine access to abortion at the state level. I also think they’re starting to feel like direct confrontation — psycho-terrorism — is more effective, as evidenced by the increasing number of attacks on clinics and workers. If women and providers feel vulnerable that will keep people from pursuing abortion, even if it remains legal. And with the election of Donald Trump, I’ve seen a resurgence of the notion that they have the weight of the law behind them.

In your book, you talk about how that bigotry is enabled by technology. Can you elaborate on that a little?

The uterus used to be a black box. It used to be, “If God wants you pregnant, you’re going to be pregnant.” But since the advent of the ultrasound in the ‘70s, we now have these 3-D and 4-D images. We’ve gone from this black box, from virtually no information, to too much information. We figured out how to do things before we figured out whether or not to do them.

So now that you have this imagery, you’re able to project personhood onto a fetus. And that allows people to a create a moral equivalency about the value of the fetus and the value of the woman. We can argue all day about whether or not a fetus is a person and when life begins, but the key question for me is: When is a woman not a person? When does she lose her agency? When does she lose her right to bodily autonomy? How can you be more vested in the well-being of a fetus than you are in the woman carrying it? You can’t give rights to a fetus that you don’t first have to take them away from a woman. So the fetishizing of reproduction and birth and procreation always occurs at the expense of women, because men can’t carry babies.

Along those lines, I wanted to ask you about a quote from your book: “It all comes back to the early Judeo-Christian narratives that say the fall of men was caused by a woman, that’s woven into our culture and it has to be deconstructed at every level.” How do you see that playing into politics now?

Well since the fall of man, women have been taking the fall for the fall. They’re always thrown under the bus, and I think that basic distrust, especially for people versed in that understanding of how we came to be, undermines the moral agency of women. That narrative and the biblical literalism that supports it has always been problematic, and as people wax conservative in a world that’s becoming more diverse and complex, it’s even more problematic. The troubling narrative of women being inherently morally flawed continues to be a problem.

That reminds me of what Vice-President Pence said about refusing to dine alone with a woman who isn’t his wife …

[Laughs] Either he thinks he’s too hot, or he doesn’t trust himself around women, right? And both of those positions are problematic! It’s also a very heteronormative narrative — does Mike Pence trust himself alone with a gay man? I wouldn’t want to pose that question to Mike Pence … But for me, gender roles and gender perceptions undermine our ability to live meaningfully together.

So how do you reconcile a lot of what the Bible says about women and gender roles?

I was reared by women, I’ve always seen women in leadership roles, and I felt very nurtured by that. So it wasn’t hard for me to let go of biblical narratives that vilify women and that entrench powerful men. As I gained a social conscience, I began to hear something different in the sacred texts. I began to see gender relationships in the sacred texts differently. I began to understand that it was problematic for me if my Christianity made me less human.

Of course, that’s led people who think very traditionally to feel confident that they can conclude I’m not legitimately, authentically Christian. For them, it’s easier to dismiss me if I’m amoral, so their chief task becomes to discredit me as a false prophet. Some people are more opposed to the fact that I lay claim to the Christian identity than to the fact that I perform abortions. And it’s not lost on me that that changes the risk calculus to what I do.

What do you mean?

Well, the person who assassinated George Tiller was a religious zealot who felt he was morally justified — that there’s such a thing as justifiable homicide. I think there are many people who feel that they have a moral obligation to harm me because I’m a false prophet, and I’m leading people astray. The risk of harm is with me like my shadow. But when I started doing this work, I decided to be mindful about what I live for, not what I might die from.

How do you think that will play out over the next four — or even eight — years?

I’m going to show up every day, and I’m going to take it one day at a time. Check back with me in eight years.